Andrey Sheptytsky

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2022) |

Andrey Sheptytsky | |

|---|---|

| Metropolitan Galicia, Archbishop of Lviv (Lemberg) | |

| |

| Church | Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church |

| Appointed | 12 December 1900 |

| Installed | 17 January 1901 |

| Term ended | 1 November 1944 |

| Predecessor | Metropolitan Archbishop Julian Sas-Kuilovsky |

| Successor | Cardinal Josyf Slipyj |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 22 August 1892 |

| Consecration | 17 September 1899 by Metropolitan Archbishop Julian Sas-Kuilovsky |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Roman Aleksander Maria Sheptytsky 29 July 1865 |

| Died | November 1, 1944 (aged 79) Lviv, Ukrainian SSR, Soviet Union |

| Buried | St. George's Cathedral, Lviv, Ukraine 49°50′19.48″N 24°0′46.19″E / 49.8387444°N 24.0128306°E |

| Nationality | Ukrainian |

| Coat of arms |  |

I am Ukrainian from my grandfather, great-grandfather. And our church and our holy ritual I love with all my heart devoting to the Lord's affair my whole life. So I know that in this regard I could not be foreign to people who have given their heart and soul for the same cause.

Andrey Sheptytsky, Pastoral letters, 2 August 1899.[1]

Andrey Sheptytsky, OSBM (Polish: Andrzej Szeptycki; Ukrainian: Митрополит Андрей Шептицький, romanized: Mytropolyt Andrei Sheptytskyi; 29 July 1865 – 1 November 1944) was the Greek Catholic Archbishop of Lviv and Metropolitan of Halych from 1901 until his death in 1944.[2] His tenure in office spanned two world wars and six political regimes: Austrian, Ukrainian, Soviet, Polish, Nazi German, and again Soviet.

According to the church historian Jaroslav Pelikan, "Arguably, Metropolitan Andriy Sheptytsky was the most influential figure ...in the entire history of the Ukrainian Church in the twentieth century".[3] The Lviv National Museum, founded by Sheptytsky in 1905, now bears his name.

The Information-Resource Center of the Ukrainian Catholic University that was opened in September 2017 also bears his name — The Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky Center.[4]

Life

[edit]Early life and education

[edit]He was born as Count Roman Aleksander Maria Szeptycki in a village 40 km west/northwest of Lviv called Prylbychi, in the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, then a crownland of the Austrian Empire.[5] His parents were Jan Kanty Szeptycki and Zofia née Fredro.[5]

The Szeptycki family descends from the Ruthenian nobility, but in the 18th century had become Polish-speaking and Catholic.[citation needed] The maternal Fredro family was descended from the Polish nobility and, through his mother,the future Metropolitan Bishop was the grandson of Polish Romantic poet Aleksander Fredro. The Szeptycki family produced a number of bishops of both Catholic rites, most notably in the 18th century. Greek Catholic Bishops of Lviv and Metropolitans of Kiev were: Athanasius and Leo, Barlaam Bazyli was also bishop of Lviv. Atanazy Andrzej was a Greek Catholic bishop of Przemyśl and Nikifor was archimanrite of Lavriv. The Latin Catholic Bishop of Płock was Hieronim Antoni Szeptycki, while his nephew Marcin was elected to the position, but did not take it. His maternal grandfather was the Polish writer Aleksander Fredro. One of his brothers, Klymentiy Sheptytsky, M.S.U., became a Studite monk, and another, Stanisław Szeptycki, became a General in the Polish Army. He was 2 m 10 cm (6 ft. 10 in.) tall.[citation needed]

Sheptytsky was baptized in the Roman rite at the parish church in Bruchnal (today Ternovytsia).[5] Sheptytsky received his education first at home and then in Lviv and later in Kraków.[5] His confessor was Jesuit Henry Nostitz-Jackowski, who was carrying out the reform of the Greek Catholic Basilian Order in Galicia. Probably under his influence, Sheptyskiy made the decision to join the Basilians, which, however, provoked opposition from his father.[5] Hence in 1883 he went to serve in the Austro-Hungarian Army but after a few months he fell sick and was forced to abandon it.[5]

Instead, he went to study law in Breslau. There he was a member of the Literary and Slavic Society run by Władysław Nehring, as well as the Upper Silesian Society and the Polish Academicians' Reading Room.[5] With his brother Alexander, he founded the Polish-Catholic Student Theological Society "Societas Hosiana" in 1884.[5] From the 1885/6 academic year, he continued his studies at Jagiellonian University in Kraków, at which time he changed his nationality declaration from "Polish" to "Ruthenian".[5] In April and May 1886 he visited Rome. From November to December 1887 he stayed in Kyiv and then in Moscow.[5] Together with mother and brother Leone he was granted an audience on March 24, 1888, with Pope Leo XIII at the Vatican. Pope blessed his intention to join Basilians.[5] On May 19, 1888 he received doctorate.[5]

According to his biographer Fr. Cyril Korolevsky, Sheptytsky's lifelong dream of creating the Russian Greek Catholic Church as a means of reuniting the Russian people with the Holy See goes back at least to his first trip to Russia in 1887. Afterwards, Sheptytsky "wrote some reflections" between October and November 1887, and expressed his belief, "that the Great Schism, which became definitive in Russia in the fifteenth century, was a bad tree, and it was useless to keep cutting the branches without uprooting the trunk itself, because the branches would always grow back."[6]

Religious and political life

[edit]Sheptytsky became a novice at the Basilian monastery in Dobromyl on June 2, 1888. He took the name, Andrew, after the younger brother of Saint Peter, Andrew the Apostle, considered the founder of the Byzantine Church and also specifically of the Ukrainian Church.[citation needed] Beginning in 1889, he studied Ukrainian there under Wojciech Baudiss.[5] He then studied at the Jesuit College in Kraków, passing the exam in 1894.[5] On September 3, 1892 he was ordained a priest in Przemyśl.[5] He was made hegumen of the Monastery of St Onuphrius in Lviv in 1896. In 1898, he took up the post of professor of moral and dogmatic theology at the Basilian seminary in Krystynopol. There he founded the Studite Order, based on the rule of St. Theodore the Studite.[5]

In 1899, following the death of Cardinal Sylwester Sembratowicz, Sheptytsky was nominated by Emperor Franz Joseph to fill the vacant position of Greek Catholic Bishop of Stanyslaviv[7] (now Ivano-Frankivsk), and Pope Leo XIII concurred. Thus he was consecrated as bishop in Lviv on 17 September 1899 by Metropolitan Julian Sas-Kuilovsky assisted by Bishop Chekhovych and Bishop Weber, the Latin-Rite auxiliary of Lviv.[8] On February 5 of that year, he received a doctorate in theological sciences in Rome, nostrified at the Faculty of Theology of the Jagiellonian University.[5] A year later, following the death of Julian Sas-Kuilovsky, Sheptytsky was appointed, at the age of thirty-six, Metropolitan of Halych, Archbishop of Lviv and Bishop of Kamenets-Podolsk; he was enthroned on 17 January 1901.[9][5] From February 1901, he sat with the House of Lords of the Imperial Council in Vienna with the title of secret counselor. He also became deputy speaker of the Galician Diet, a position he held until 1912.[5]

He was active in promoting the revival and expansion of the Eastern Catholic Churches in the territory of Russian Empire, visiting incognito that country several times and secretly ordaining bishops and priests there. He also took an active part in the Velehrad congresses. He also strove for the revival of the Belarusian Greek Catholic Church, and to this end contacted important leaders of the movement for Belarusian nationalism, including Ivan Lutskevich.[5]

Sheptytsky supported the Ukrainian national movement, founding a Greek Catholic seminary in Stanislaviv, supported the opening of a Ukrainian gymnasium there, and a Ukrainian university and hospital in Lviv.[5] He sponsored an exhibition of Ukrainian artists in Lviv in 1905, led a Ukrainian pilgrimage to Palestine, and led a Ukrainian delegation to Emperor Franz Joseph seeking reform of the electoral law.[5] At the same time, he sought to prevent Polish-Ukrainian nationalist conflicts in Galicia. In 1904, he issued a pastoral letter to Polish Greek Catholics, urging them to love their own nation and warning against harming others under the guise of patriotism.[5] In 1908, he harshly condemned the assassination of Galician governor Andrzej Kazimierz Potocki by Ukrainian student Myroslav Sichinskyi.[5]

Sheptytsky visited North America in 1910 where he met with Ukrainian Greek Catholic immigrant communities in the United States;[10] attended the twenty-first International Eucharistic Congress in Montreal; toured Ukrainian communities in Canada; and invited the Redemptorist fathers ministering in the Byzantine rite to come to Ukraine.

World War I

[edit]After the outbreak of World War I, Sheptytsky proposed eventual creation of the Ukrainian state out of the Russian territories, he also appealed believers to stay loyal to the emperor of Austria.[5] When Russians entered Lviv Sheptytsky was arrested on September 18, 1914 and sent to Kyiv. While being there he tried to recreate union by consecrating Yosif Botsyan as bishop of Lutsk.[5] For this activity, he was deported to Nizhny Novgorod, then Kursk, after that to monastery of Saint Euthymius in Suzdal and finally to Yaroslav.[11][5] He was released in 1918 and returned to Lviv from the Russian Empire. Bolsheviks destroyed his parents' rural house in Prylbychi where he was born.[11] During the destruction the family archives were lost.[11] Sheptytsky again visited the United States in 1920.[12]

World War II

[edit]After the German invasion of Poland, Sheptytsky issued a pastoral letter appealing not to succumb to propaganda. On October 9, 1939, after the Soviets occupied eastern Poland, without the consent of the Holy See, he created a new territorial division of the Greek Catholic Church on the territory of the USSR.[5] During the Soviet occupation, he tried to protect the independence of the Church from control by the Soviet authorities. He protested the atheization of youth, organized synods and secretly ordained bishops. He also contacted the Polish underground (ZWZ) to ease Polish-Ukrainian relations.[5]

Sheptytsky welcomed the Wehrmacht entering Lviv and supported the OUN-B's declaration of Ukrainian independence on June 30, 1941. After the dissolution of Yaroslav Stetsko's government, he became honorary chairman of the Ukrainian Council of Seniors. On July 22, 1941, in a letter to Joachim von Ribbentrop, Germany's foreign minister, he protested against the annexation of Eastern Galicia to the General Government.[5] In August 1941, he assumed the protectorate of the newly established Ukrainian Red Cross. Gradually, he developed a dislike for the Nazi Party, being disgusted by their policies toward the civilian population. In June 1942, he promulgated the document The Ideal of Our National Life, in which he presented a vision of an independent, united Ukraine united by a single Church in union with the Holy See.[5] In February 1942, he signed a letter to Adolf Hitler issued by the OUN-M opposing German policies and demanding the establishment of an independent Ukraine. Nevertheless, in the summer of 1943, Sheptytsky appointed chaplains for the forming Ukrainian SS-Galizien division.[5]

This was because Sheptytsky initially supported the 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Galician), even blessing new recruits.[13] According to his close friend Rabbi David Kahane, however, Sheptytsky had believed that the Division would be used to fight Stalinism and personally expressed disgust in a conversation with the Rabbi about the Division's subsequent role as perpetrators of the Holocaust in Ukraine.

Also in February 1942, Sheptytsky sent a letter to Heinrich Himmler protesting the Holocaust in Ukraine.[5] During World War II, he saved at least 150-200 Jews, mainly children, by hiding them in Greek Catholic orphanages, monasteries, and convents, where they were trained in how to pass as Greek Catholics. He collaborated in this work with the superiors of the Studite orders, Sister Josefa (Helena Witter) and his brother Klymentiy Sheptytsky.[14][5] At his archbishop's residence in Lviv, he gave shelter to Kurt Lewin, the son of Jecheskiel Lewin, the chief rabbi of the Lviv progressive synagogue.[5]

In August 1942, Sheptytsky sent a letter to Pius XII in which he reported on the brutal Nazi policies and unequivocally condemned the murder of Jews, and also admitted that his original assessment of the Germans' attitude toward Ukrainians was wrong.[5] He also issued on November 21, 1942, the pastoral letter, "Thou Shalt Not Kill",[15] to protest Nazi atrocities.

According to historian Ronald Rychlak, "A German Foreign Office agent named 'Frederic' was sent in a tour through various Nazi-occupied and satellite countries during the war. He wrote in his confidential report to the German Foreign Office on September 19, 1943, that Metropolitan Archbishop Andrey Sheptytsky, of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, remained adamant in saying that the killing of Jews was an inadmissible act. 'Frederic' went on to comment that Sheptytsky made the same statements and used the same phrasing as the French, Belgian, and Dutch bishops, as if they were all receiving instructions from the Vatican."[16]

One of the rabbis whose life was saved by Metropolitan Sheptytsky, David Kahane, stated: "Andrew Sheptytsky deserves the undying gratitude of the Jews and the honorific title 'Prince of the Righteous'".[17] In addition, among the Jews who, thanks to Sheptytsky's help, survived the war were Lili Pohlmann and her mother, Adam Daniel Rotfeld (later Poland's foreign minister), two sons of the chief rabbi of Katowice (including the prominent cardiac surgeon Leon Chameides).[18]

Sheptytsky maintained contacts with the Polish underground and tried to mediate in the Polish-Ukrainian conflict. In the autumn of 1941, he met with Jerzy Braun, an envoy of Government Delegate for Poland Cyryl Ratajski and General Stefan Rowecki, Commander-in-Chief of the ZWZ, to whom he made a proposal to delegate two Ukrainian representatives to the National Council in London.[5] Sheptytsky was aware of the ongoing genocide of the Polish population organized by the forces of OUN-B and the UPA since the summer of 1943. He did not condemn it outright, but in a pastoral letter of August 10, 1943, he called for saving the lives of those in danger, and in another of August 31, he urged both sides to stop fighting. In early 1944, he condemned the killings and their perpetrators, regardless of their motives. In a "word for Easter" dated April 16, 1944, he called for harmony between neighbors.[5]

During this period he secretly consecrated Josyf Slipyj as his successor. Sheptytsky died in 1944 and is buried in St. George's Cathedral in Lviv. In 1958 the cause for his canonization was begun, but stalled at the behest of Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski. Pope Francis approved his life as being one of heroic virtue on 16 July 2015, thus proclaiming him to be Venerable.

Views

[edit]Sheptytsky in the early years of his episcopacy expressed strong support for a celibate Eastern Catholic clergy. Yet he said to have changed his mind after years in Imperial Russian prisons where he encountered the faithfulness of married Russian and Ukrainian Orthodox priests and their wives and families. After this, he fought Latin Catholic leaders who attempted to require clerical celibacy among Eastern Catholic priests.[19]

Sheptytsky was also a patron of artists, students, including many Orthodox Christians, and a pioneer of ecumenism—he also opposed the Second Polish Republic policies of linguistic imperialism, coercive Polonisation, and the forced conversion of Greek Catholic and Orthodox Ukrainians into Latin Rite Catholics.[20] He strove for reconciliation between ethnic groups and wrote frequently on social issues and spirituality. He also founded the Studite and Ukrainian Redemptorist orders, a hospital, the National Museum, and the Theological Academy. He actively supported various Ukrainian organizations such as the Prosvita and in particular, the Plast Ukrainian Scouting Organization, and donated a campsite in the Carpathian Mountains called Sokil and became the patron saint of the Plast fraternity Orden Khrestonostsiv.

Commemoration

[edit]Jews who were saved thanks to actions of Andrey Sheptytsky have lobbied Yad Vashem for years to have him named Righteous Among the Nations, just as his brother Klymentiy Sheptytsky had been, but so far Yad Vashem has not done so, mostly due to concerns with his initial belief that German invaders would be better for Ukraine than the Soviet Union had been.[21]

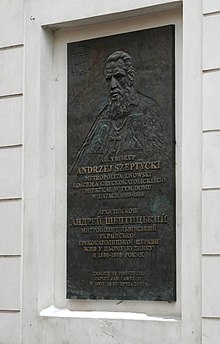

The first monument to Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky was erected during his lifetime in 1932. It was destroyed by the Soviets in 1939. A new monument to Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky was inaugurated in Lviv on 29 July 2015, the 150th anniversary of his birth.[22]

On 19 September 2024, the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine voted to rename the city of Chervonohrad to Sheptytskyi in his honor.[23]

Images

[edit]-

Father Andrey in Rome, 1921

-

Archbishop Andreas Szeptycki in Philadelphia, October 1910.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Hakh, I. Great descendant of the old family (Великий нащадок давнього роду). Zbruch (newspaper). 31 July 2015

- ^ "Митрополит Андрей Шептицький - Україна Incognita". incognita.day.kyiv.ua. Archived from the original on 2020-04-07. Retrieved 2020-04-09.

- ^ Pelikan, Jaroslav (1990). Confessor Between East and West. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8028-3672-0.

- ^ "About the Center". UKU Center (in Ukrainian). 2018-05-11. Retrieved 2019-08-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al Nowak, Magdalena. "Roman Aleksander (w zakonie Andrzej) Szeptycki (Szeptyc'kyj)". www.ipsb.nina.gov.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2023-08-08.

- ^ Cyril Korolevsky (1993), Metropolitan Andrew (1865-1944), translated and revised by Serge Keleher. Eastern Christian Publications, Fairfax, Virginia. Page 249.

- ^ Kitsoft. "Єгипет - July 29 – 150 anniversary of the birth of Andrey Sheptytsky, Metropolitan of Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church". egypt.mfa.gov.ua. Retrieved 2020-04-09.

- ^ Athanasius D. McVay (10 April 2008). "The Reluctant-to-Accept and the Reluctantly-Accepted Bishop". Annales Ecclesiae Ucrainae. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ "Archbishop Andrij Aleksander Szeptycki (Sheptytsky), O.S.B.M." Catholic-Hierarchy.org. David M. Cheney. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- ^ "More Growing Pains". Ss. Cyril and Methodius Ukrainian Catholic Church. Retrieved 2024-08-18.

- ^ a b c Senkivska, N. Metropolitan Andrei: life story in retro-photographs (Митрополит Андрей: життєпис у ретро-світлинах.). Zbruc. 1 November 2016

- ^ "More Growing Pains". Ss. Cyril and Methodius Ukrainian Catholic Church. Retrieved 2024-08-18.

- ^ Serbyn p.65

- ^ Holocaust Survivor Speaks at UCU, Praises Sheptytskys, Ukrainian Catholic University News

- ^ "Не убий!". Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ^ Ronald J. Rychlak (2010), Hitler, the War and the Pope, Revised and Expanded, Our Sunday Visitor, page 328.

- ^ Petro Mirchuk: The Matter of the Metropolitan of the Ukrainian Catholic Church, Andrij Sheptytsky

- ^ "Historia pomocy - Rodzina Szeptyckich | Polscy Sprawiedliwi". sprawiedliwi.org.pl. Retrieved 2023-08-10.

- ^ "American Carpatho-Russian Orthodox Diocese of the USA – Mandated Celibacy Among US Eastern Catholic Priests Theme of Seminar in Rome". Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ^ Cuius Regio, Time, 24 October 1938

- ^ "The Jewish Week: Righteous Gentile Or Nazi Supporter? Wartime leader of Ukrainian church sheltered many Jews, but the decades-long campaign has not brought Yad Vashem's highest honor. 04/09/12 By Steve Lipman". Archived from the original on 2016-10-11. Retrieved 2016-09-11.

- ^ "Metropolitan Andriy Sheptytsky monument unveiled in Lviv". EMPR: Russia - Ukraine war news, latest Ukraine updates. 2015-07-30. Retrieved 2020-08-12.

- ^ Проект Постанови про перейменування окремих населених пунктів та районів [Draft resolution on renaming individual populated places and raions]. Retrieved 2024-09-19.

Further reading

[edit]- Cyrille Korolevskij, Metropolitan Andrew (1865–1944), Translated and Revised by Serge Keleher, Stauropegion, 1993, Lviv.

- Aharon Weiss, Andrei Sheptytsky in Encyclopedia of the Holocaust vol. 4, pp. 1347–8

- The Ukrainian Division Halychyna by Dr. Roman Serbyn

Films

[edit]- Yad Vashem Interviews a Jew Whom Sheptytsky Rescued During the Holocaust on YouTube

- Recording of a Sermon by Metropolitan Sheptytsky on YouTube

- Saved by Sheptytsky – a documentary about some of 150 Holocaust survivors saved by Sheptytsky as kids on YouTube

External links

[edit] Media related to Andrey Sheptytsky at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Andrey Sheptytsky at Wikimedia Commons- (in English) Andrei Sheptytsky at the Encyclopedia of Ukraine

- Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky Institute of Eastern Christian Studies

- Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytskyi who was called the "apostle of Ukrainian truth", Welcome to Ukraine

- [1] (Ukrainian, pdf of scanned images)

- [2] (English, pdf)

- He Welcomed the Nazis and Saved Jews

- Metropolitan Sheptytsky, Apostle of Church Unity

- Sheptytsky Award Tablet, Vladislav Davidzon

- 1865 births

- 1944 deaths

- Catholic resistance to Nazi Germany

- Szeptycki family

- Clergy from Lviv Oblast

- Clergy from the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria

- Eastern Catholic priests from Austria-Hungary

- Ukrainian Austro-Hungarians

- Polish Austro-Hungarians

- Ukrainian nobility

- 19th-century Polish nobility

- Ukrainian philanthropists

- Ukrainian anti-communists

- 19th-century Eastern Catholic archbishops

- 20th-century Eastern Catholic archbishops

- 20th-century venerated Christians

- Venerated Catholics by Pope Francis

- Catholic saints and blesseds of the Nazi era

- Venerated Eastern Catholics

- Order of Saint Basil the Great

- Burials at St. George's Cathedral, Lviv

- Ukrainian prisoners and detainees

- People who rescued Jews during the Holocaust

- Prisoners and detainees of Russia

- Founders of Eastern Catholic religious communities

- Eastern Catholic writers

- 20th-century Polish nobility

- Metropolitans of Galicia (1808-2005)

- Leaders of the Ruthenian Uniate Church

- Andrey Sheptytsky