Fascism in the United States

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Portuguese. (February 2025) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Fascism in the United States is an expression of fascist political ideology that dates back over a century in the United States of America, with roots in white supremacy, nativism, and violent political extremism. Though an often overlooked chapter in US history that was overshadowed by fascism in Europe, and particularly by Nazi Germany, far-right authoritarian movements have long been a part of the political landscape in the US.[1]

When looking to the origins of fascism in the US, scholars point to early 20th-century groups like the Ku Klux Klan, and domestic proto-fascist organizations during the Great Depression, which flourished amid social and political unrest. Alongside homegrown movements, German-backed political formations during World War II worked to sway US public opinion towards the Nazi cause. Black antifascist activism and other resistance movements played a significant role in confronting these ideologies.[1]

The recent resurgence of fascist rhetoric in contemporary US politics, particularly under the administration of Donald Trump, has highlighted the persistence of far-right ideology. Events like the 2017 Charlottesville rally have exposed the racism, antisemitism and white supremacy still latent within the politics of the US. This has raised concerns about the future of American democracy.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Fascism |

|---|

|

Early origins

[edit]The origins of fascism in the United States date back to the late 19th century, during the passage of Jim Crow laws in the American South, the rise of the eugenicist discourse in the US, and the intensification of nativist and xenophobic hostility towards immigrants. During the early 20th century, several groups were formed in the United States that contemporary historians have classified as fascist organizations – with a prominent example being the Ku Klux Klan.[1]

Ku Klux Klan

[edit]

The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) or "the Klan", is an American Protestant-led Christian extremist, white supremacist, far-right hate group that was founded in 1865 during the post-civil war reconstruction era in the devastated South.

Scholars have characterized the Klan as America's first terrorist group,[2][3][4][5] and compared its emergence to fascist trends in Europe.[6] Historian Peter Amann states that, "Undeniably, the Klan had some traits in common with European fascism—chauvinism, racism, a mystique of violence, an affirmation of a certain kind of archaic traditionalism—yet their differences were fundamental. ...[The KKK] never envisioned a change of political or economic system."[7]

The first Klan, founded by Confederate veterans, assaulted and murdered politically active Black people and their white political allies in the South.[8] The second Klan started in 1915 as a small group in Georgia, and flourished nationwide by the mid-1920s.[9]

Inter-war period

[edit]The rise of fascism in Europe during the interwar period raised concerns in the U.S. but European fascist regimes were largely viewed in a positive light by the American ruling class. This was due to the fact that fascist interpretations of ultranationalism allowed a nation to gain a significant amount of economic influence in the Western world and permitted a nation's government to destroy leftists and labour movements.[10]

Sympathy with Italian fascism

[edit]During the 1920s, American scholars frequently wrote about the rise of Italian fascism under Benito Mussolini, but few of them supported it; however, Mussolini's fascist policies did initially gain widespread support among Italian Americans.[11][12]

William Phillips, who served as the American ambassador to Italy, was "greatly impressed by the efforts of Benito Mussolini to improve the conditions of the masses" and found "much evidence" in support of the fascist argument that "they represent a true democracy in as much as the welfare of the people is their principal objective".[13]

Phillips found Mussolini's achievements "astounding [and] a source of constant amazement", and greatly admired his "great human qualities". United States Department of State officials enthusiastically agreed with Phillips' assessment, praising Italian fascism for having "brought order out of chaos, discipline out of license, and solvency out of bankruptcy", as well as Mussolini's "magnificent" achievements in Ethiopia during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War.[13]

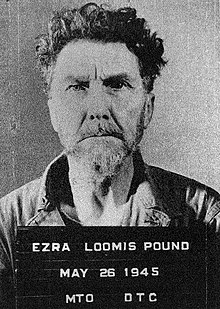

The American poet Ezra Pound moved from the United States to Italy in 1924, and he became a loyal supporter of Benito Mussolini, the founder of a fascist state. He wrote articles and produced radio broadcasts that were critical of the United States, international bankers, Franklin Roosevelt, and the Jews. His propaganda was poorly received in the U.S.[14]

The Black Legion

[edit]In 1925, Virgil Effinger established the paramilitary Black Legion, a violent white supremacist offshoot of the KKK that sought to establish fascism in the United States by launching a revolution against the federal government.[15] The Black Legion was active in the Midwestern United States in the 1920s and the 1930s and grew to prominence during the Great Depression. The FBI estimated that its membership numbered "at 135,000, including a large number of public officials, including Detroit's police chief."[16] Historians have suggested lower estimates.[17][18]

The Black Legion is widely viewed as having been an even more violent and radical offshoot of the Klan.[19] In 1936, the group was suspected of having killed as many as 50 people, according to the Associated Press, including Charles Poole, an organizer for the federal Works Progress Administration. Eleven men were found guilty of Poole's murder.[16] The Associated Press described the organization as "a group of loosely federated night-riding bands operating in several States without central discipline or common purpose beyond the enforcement by lash and pistol of individual leaders' notions of 'Americanism'."[20] Nearly 50 Legionnaires were ultimately convicted of murder, conspiracy to commit murder, kidnapping, arson, and perjury.[21] Although it was responsible for numerous attacks, the Black Legion remained limited in size and ultimately petered out.[15]

Father Charles Coughlin

[edit]

Father Charles Coughlin was a Roman Catholic priest who hosted a prominent radio program in the late 1930s, on which he often ventured into politics. In 1932, he backed and welcomed the election of President Franklin Roosevelt, but the two had a falling out after 1934. His radio program and his newspaper, "Social Justice", denounced Roosevelt, as well as the "big banks" and "the Jews".[22] When the United States entered World War II, the U.S. government took his radio broadcasts off the air, and blocked his newspaper from the mail. He abandoned politics, but continued to be a parish priest until his death in 1979.[22]

The American architect-to-be Philip Johnson was a correspondent (in Germany) for Coughlin's newspaper between 1934 and 1940 (before beginning his architectural career). He wrote articles that were favorable to the Nazis and critical of "the Jews", as well as taking part in a Nazi-sponsored press tour, in which he covered the 1939 Nazi invasion of Poland. He quit the newspaper in 1940, was investigated by the FBI and was eventually cleared for army service in World War II. Years later he would refer to these activities as "the stupidest thing[sic] I ever did ... [which] I never can atone for".[23]

The rise of Hitler

[edit]Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933.[24] In the years that followed, prior to the outbreak of World War II, some German-Americans attempted to create pro-Nazi movements in the U.S., often bearing swastikas and wearing uniforms.[25] These groups had little to do with Nazi Germany, and they lacked support from the wider German-American community.[26]

Across the US, so many small groups sprang up wearing uniforms and identifying as fascist that in 1934, the American Civil Liberties Union released a pamphlet titled “Shirts! A Survey of the New ‘Shirt’ Organizations in the United States Seeking a Fascist Dictatorship” detailing the gold, silver, brown, black, gray, white and blue-coloured shirt liveries of the different emergent fascist groups.[27]

In May 1933, Heinz Spanknöbel, a German immigrant to America, received authority from Rudolf Hess, the deputy führer of Germany, to form an official American branch of the Nazi Party. The branch was known as the Friends of New Germany in the U.S.[26] The Nazi Party referred to it as the National Socialist German Workers' Party of the U.S.A.[24] Though the party had a strong presence in Chicago, it remained based in New York City, having received support from the German consul in the city. Spanknöbel's organization was openly pro-Nazi. Members stormed the German-language newspaper New Yorker Staats-Zeitung and demanded that the paper publish articles sympathetic to Nazis. Spanknöbel's leadership was short-lived, as he was deported in October 1933 following revelations that he had not registered as a foreign agent.[26]

Some American corporations had branches in neutral countries that traded with Germany after the U.S. declared war in late 1941.[28]

German American Bund

[edit]

The German American Bund was the most prominent and well-organized fascist organization in the United States. It was founded in 1936, following the model of Hitler's Nazi Germany. It appeared shortly after the founding of several smaller groups, including the Friends of New Germany and the Silver Legion of America, founded in 1933 by William Dudley Pelley and the Free Society of Teutonia. The Friends of New Germany dissolved in December 1935 when Hess ordered all German citizens to leave the group after realizing that the organization was not beneficial to advancing their cause.[29]

The German American Bund, led by Fritz Kuhn, was formed in 1936 and lasted until America formally entered World War II in 1941. The Bund existed with the goal of a united America under ethnic German rule and following Nazi ideology. It proclaimed communism as their main enemy and expressed anti-Semitic attitudes.[26] After March 1, 1938, membership in the German-American Bund was only open to American citizens of German descent.[30][31] Its main goal was to promote a favorable view of Nazi Germany. The Bund was very active, providing its members with uniforms and encouraging participation in "training camps".[32]

Inspired by the Hitler Youth, the Bund created its youth division, where members "took German lessons, received instructions on how to salute the swastika, and learned to sing the 'Horst Wessel Lied' and other Nazi songs."[33] The Bund continued to justify and glorify Hitler and his movements in Europe during the outbreak of World War II. After Germany invaded Poland in 1939, Bund leaders released a statement demanding that America stay neutral in the ensuing conflict and expressed sympathy for Germany's war effort. The Bund reasoned that this support for the German war effort was not disloyal to the United States, as German-Americans would "continue to fight for a Gentile America free of all atheistic Jewish Marxist elements."[33]

The Bund held rallies with Nazi insignia and procedures such as the Hitler salute. Its leaders denounced the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Jewish-American groups, Communism, "Moscow-directed" trade unions and American boycotts of German goods.[34] They claimed that George Washington was "the first Fascist" because he did not believe that democracy would work.[35]

The high point of the Bund's activities was their rally at Madison Square Garden in New York City on February 20, 1939, with around 20,000 people in attendance.[36] The anti-Semitic Speakers repeatedly referred to President Roosevelt "Frank D. Rosenfeld", calling his New Deal the "Jew Deal", as well as denouncing the supposed Bolshevik-Jewish American leadership.[37] The rally ended with violence between protesters and the Bund's "storm-troopers".[38] In 1939, America's top fascist, the Bund's leader Fritz Julius Kuhn, was investigated by the city of New York, and was found to be embezzling the Bund's funds for his own use. He was arrested, his citizenship was revoked, and he was deported.

In 1940, the U.S. Army organized a draft in an attempt to bring citizens into military service. The Bund advised its members not to submit to the draft. On the basis of this piece of advice, the Bund was outlawed by the U.S. government, and Kuhn fled to Mexico.

After many internal and leadership disputes, the Bund's executive committee agreed to disband the party on December 8, 1941, the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor. On December 11, 1941, the United States formally declared war on Germany, and Treasury Department agents raided Bund headquarters. The agents seized all records and arrested 76 Bund leaders.[33]

World War II

[edit]During World War II, Canada and the United States battled the Axis powers. As part of the war effort, they suppressed the fascist movements within their borders, which were already weakened by the widespread public perception that they were fifth columns. This suppression consisted of the internment of fascist leaders, the disbanding of fascist organizations, the censorship of fascist propaganda and pervasive government propaganda against fascism. In the U.S., this campaign of suppression culminated in "The Great Sedition Trial" of November 1944, in which George Sylvester Viereck, Lawrence Dennis, Elizabeth Dilling, William Dudley Pelley, Joe McWilliams, Robert Edward Edmondson, Gerald Winrod, William Griffin, and, in absentia, Ulrich Fleischhauer were all put on trial for aiding the Nazi cause, supporting fascism and isolationism. After the death of the judge however, a mistrial was declared and all of the charges were dropped.[39]

Post-World War II

[edit]In the 1980s, the Office of Special Investigations estimated around ten thousand Nazi war criminals entered the United States from Eastern Europe after the conclusion of World War II, albeit the number has since been determined to have been much smaller.[40][41]

Some were brought in Operation Paperclip, a project to bring German scientists and engineers to the U.S. Most Nazi collaborators entered the United States through the 1948 and 1950 Displaced Persons Acts and the Refugee Relief Act of 1953. Supporters of the acts exhibited only slight awareness that Nazi war criminals would exploit the legislation to enter the United States. Most of the supporters' concern was about disallowing known communists from entering. This shift of focus was likely due to the pressures of the Cold War in the years after World War II, when the United States focused on countering Soviet communism more than Nazism.[40]

During the 1950s, the Immigration and Naturalization Service conducted several investigations into suspected Nazi war criminals. No official trials came from these investigations. The Holocaust and the possibility of Nazi collaborators living in the country entered the national discussion in the 1960s with the trial of Adolf Eichmann, accusations of war criminals during Soviet war crimes trials, and a series of articles published by Charles R. Allen detailing the presence of Nazi war criminals living in the U.S. The federal government began to focus on uncovering Nazi war criminals remaining in the country.[40]

Public awareness of the Holocaust and remaining Nazi war criminals increased in the 1970s. Many cases made headline news. The case of Hermine Braunsteiner, the first Nazi war criminal to be extradited from the United States, received widespread media coverage. The case triggered the Immigration and Naturalization Service to locate Nazi collaborators further. By the late 1970s, INS addressed thousands of cases, and the U.S. government formed the Office of Special Investigations, which was dedicated to locating Nazi war criminals in the United States.[40]

Neo-Nazism

[edit]Neo-Nazism began to emerge as an ideology from the 1970s, seeking to revive and implement Nazi ideology.[42] In the United States, organizations such as the American Nazi Party, the National Alliance and White Aryan Resistance were formed during the second half of the 20th century.[43] While initially formed of distinctive movements, in the 21st century, many US Neo-Nazi groups have moved towards more decentralized organization and online social networks with a terroristic focus.[44]

American Nazi Party

[edit]In 1959, the American Nazi Party was founded by George Lincoln Rockwell, a former U.S. Navy commander, who was dismissed from the Navy due to his espousal of fascist political views.[45]

Headquartered in Arlington, Virginia, the organization was originally named the World Union of Free Enterprise National Socialists, a name to denote opposition to state ownership of property, the same year—it was renamed the American Nazi Party in order to attract 'maximum media attention'.[46]

The party was based largely upon the ideals and policies of Adolf Hitler's Nazi Party in Germany during the Nazi era, and embraced its uniforms and iconography. Since the late 1960s, a number of small groups had used the name "American Nazi Party" with most being independent of each other and disbanding before the 21st century.[47][A]

On August 25, 1967, Rockwell was shot and killed in Arlington by John Patler, a former party member who had previously been expelled by Rockwell due to his espousal of his alleged "Bolshevik leanings".[45] The Party was dissolved in 1983.

National Alliance

[edit]The National Alliance is a neo-Nazi,[51]white supremacist[51][52][53][54] political organization founded by William Luther Pierce, author of The Turner Diaries, in 1974 and based in Mill Point, West Virginia. It was the largest and most active neo-Nazi group in the United States in the 1990s.[55][43] In 2002, its membership was estimated at 2,500 with an annual income of $1 million.[56]

Its membership declined after Pierce's death in 2002, and after a split in its ranks in 2005, became largely defunct.[51][57] According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, the National Alliance had lost most of its members by 2020 but is still visible in the U.S.[55][44] Other groups, such as Atomwaffen Division have taken its place.[58]

National Socialist Movement

[edit]The National Socialist Movement (NSM or NSM88)[fn 1] is a US-based Neo-Nazi organization that was founded in 1974.[59][60] The NSM has been described by the Anti-Defamation League as "one of the more explicitly neo-Nazi groups in the United States." It seeks the transformation of the United States into a white ethnostate from which Jews, non-Whites, and members of the LGBTQ community would be expelled and barred from citizenship.[61][62]

Once considered to be the largest and most prominent neo-Nazi organization in the United States, its membership has plummeted since the late 2010s.[61] It is a part of the Nationalist Front[63] and is classified as a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center.[62]

2017 Charlottesville rally

[edit]

From 11 to 12 August 2017, the Unite the Right rally, a white-nationalist event,[64][65][66] took place in Charlottesville, Virginia.[67][68][69] It was organized by Richard B Spencer and Jason Kessler, both Neo-Nazism adherents.[70][71][72][73] Marchers included members of the alt-right,[74] neo-Confederates,[75] neo-fascists,[76] white nationalists,[77] neo-Nazis,[78] Klansmen,[79] and far-right militias.[80]

Some groups chanted racist and antisemitic slogans and carried weapons, Nazi and neo-Nazi symbols, the valknut, Confederate battle flags, Deus vult crosses, flags, and other symbols of various past and present antisemitic and anti-Islamic groups.[85] The organizers' stated goals included the unification of the American white nationalist movement[74] and opposing the proposed removal of the statue of General Robert E. Lee from Charlottesville's former Lee Park.[83][86] The rally sparked a national debate over Confederate iconography, racial violence, and white supremacy.[87]

Patriot Front

[edit]Patriot Front is an American white supremacist and neo-fascist hate group.[88] Part of the broader alt-right movement, the group split off from the neo-Nazi organization Vanguard America in the aftermath of the Unite the Right rally in 2017.[89][90][91][92]

Patriot Front's aesthetic combines traditional Americana with fascist symbolism. Internal communications within the group indicated it had approximately 200 members as of late 2021.[93] According to the Anti-Defamation League, the group generated 82% of reported incidents in 2021 involving distribution of racist, antisemitic, and other hateful propaganda in the United States, comprising 3,992 incidents, in every continental state.[94]

Donald Trump and fascism

[edit]

Some scholars have drawn comparisons between the political styles of Donald Trump and fascist leaders. Such assessments began during Trump's 2016 presidential campaign,[95][96] and continued throughout the first Trump presidency as he appeared to court far-right extremists,[97][98][99][100] including his attempts to overturn the 2020 United States presidential election after losing to Joe Biden,[101] and culminating in the 2021 United States Capitol attack.[102]

The attack on the United States Capitol by supporters of Donald Trump on January 6, 2021, has been compared to the Beer Hall Putsch,[103] a failed coup attempt in Germany by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler against the Weimar government in 1923.[104]

In "Trump and the Legacy of a Menacing Past", Henry Giroux argued that understanding the rise of "fascist politics" in the US necessitates examining the power of language, social media, and public spectacle in fostering an American-style fascism.[105] Jason Stanley argued in 2018 that Trump employed "fascist techniques" to mobilize his base and weaken liberal democratic institutions.[106] Trump has also been compared to Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi,[107] while former aide Anthony Scaramucci compared Trump to Benito Mussolini and Augusto Pinochet.[108]

Anti-fascism

[edit]

During World War II

[edit]

Anti-fascist Italian expatriates in the United States founded the Mazzini Society in Northampton, Massachusetts in September 1939 to work toward ending Fascist rule in Italy. As political refugees from Mussolini's regime, they disagreed among themselves whether to ally with Communists and anarchists or to exclude them. The Mazzini Society joined with other anti-Fascist Italian expatriates in the Americas at a conference in Montevideo, Uruguay in 1942. They unsuccessfully promoted one of their members, Carlo Sforza, to become the post-Fascist leader of a republican Italy. The Mazzini Society dispersed after the overthrow of Mussolini as most of its members returned to Italy.[109][110]

Post-World War II

[edit]During the Second Red Scare which occurred in the United States in the years that immediately followed the end of World War II, the term "premature anti-fascist" came into currency and it was used to describe Americans who had strongly agitated or worked against fascism, such as Americans who had fought for the Republicans during the Spanish Civil War, before fascism was seen as a proximate and existential threat to the United States (which only occurred generally after the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany and only occurred universally after the attack on Pearl Harbor). The implication was that such persons were either Communists or Communist sympathizers whose loyalty to the United States was suspect.[111][112][113] However, the historians John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr have written that no documentary evidence has been found of the US government referring to American members of the International Brigades as "premature antifascists": the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Office of Strategic Services, and United States Army records used terms such as "Communist", "Red", "subversive", and "radical" instead. Indeed, Haynes and Klehr indicate that they have found many examples of members of the XV International Brigade and their supporters referring to themselves sardonically as "premature antifascists".[114]

1980s onwards

[edit]Modern antifa politics can be traced to opposition to the infiltration of Britain's punk scene by white power skinheads in the 1970s and 1980s, and the emergence of neo-Nazism in Germany following the fall of the Berlin Wall. In Germany, young leftists, including anarchists and punk fans, renewed the practice of street-level anti-fascism. Columnist Peter Beinart writes that "in the late '80s, left-wing punk fans in the United States began following suit, though they initially called their groups Anti-Racist Action (ARA) on the theory that Americans would be more familiar with fighting racism than they would be with fighting fascism".[115]

Dartmouth College historian Mark Bray, author of Antifa: The Anti-Fascist Handbook, credits the ARA as the precursor of modern antifa groups in the United States. In the late 1980s and 1990s, ARA activists toured with popular punk rock and skinhead bands in order to prevent Klansmen, neo-Nazis and other assorted white supremacists from recruiting.[116][117] Their motto was "We go where they go" by which they meant that they would confront far-right activists in concerts and actively remove their materials from public places.[118] In 2002, the ARA disrupted a speech in Pennsylvania by Matthew F. Hale, the head of the white supremacist group World Church of the Creator, resulting in a fight and twenty-five arrests. In 2007, Rose City Antifa, likely the first group to utilize the name antifa, was formed in Portland, Oregon.[119][120][121] Other antifa groups in the United States have other genealogies. In 1987 in Boise, Idaho, the Northwest Coalition Against Malicious Harassment (NWCAMH) was created in response to the Aryan Nation's annual meeting near Hayden Lake, Idaho. The NWCAMH brought together over 200 affiliated public and private organizations, and helped people, across six states--Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Washington and Wyoming.[122] In Minneapolis, Minnesota, a group called the Baldies was formed in 1987 with the intent to fight neo-Nazi groups directly. In 2013, the "most radical" chapters of the ARA formed the Torch Antifa Network[123] which has chapters throughout the United States.[124] Other antifa groups are a part of different associations such as NYC Antifa or operate independently.[125]

Modern antifa in the United States is a highly decentralized movement. Antifa political activists are anti-racists who engage in protest tactics, seeking to combat fascists and racists such as neo-Nazis, white supremacists, and other far-right extremists.[126] This may involve digital activism, harassment, physical violence, and property damage[127] against those whom they identify as belonging to the far-right.[128][129] According to antifa historian Mark Bray, most antifa activity is nonviolent, involving poster and flyer campaigns, delivering speeches, marching in protest, and community organizing on behalf of anti-racist and anti-white nationalist causes.[130][120]

A June 2020 study by the Center for Strategic and International Studies of 893 terrorism incidents in the United States since 1994 found one attack staged by an anti-fascist that led to a fatality (the 2019 Tacoma attack, in which the attacker, who identified as an anti-fascist, was killed by police), while attacks by white supremacists or other right-wing extremists resulted in 329 deaths.[131][132][133] Since the study was published, one homicide has been connected to anti-fascism.[131] A DHS draft report from August 2020 similarly did not include "antifa" as a considerable threat, while noting white supremacists as the top domestic terror threat.[134]

There have been multiple efforts to discredit ANTIFA groups via hoaxes on social media, many of them false flag attacks originating from alt-right and 4chan users posing as antifa backers on Twitter.[135][136] Some hoaxes have been picked up and reported as fact by right-leaning media.[137][138]

During the George Floyd protests in May and June 2020, the Trump administration blamed ANTIFA for orchestrating the mass protests. Analysis of federal arrests did not find links to ANTIFA.[139] There had been repeated calls by the Trump administration to designate antifa as a terrorist organization,[140] a move that academics, legal experts and others argued would both exceed the authority of the presidency and violate the First Amendment.[141][142][143]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Despite sharing ideological roots, the phrase 'American Nazi Party' should not be conflated with the German American Bund or German American Federation (German: Amerikadeutscher Bund; Amerikadeutscher Volksbund, AV), which was an American Nazi organization established in 1936 to succeed Friends of New Germany (FONG), the new name being chosen to emphasize the group's American credentials after press criticism that the organization was unpatriotic.[48][49] The Bund was to consist only of American citizens of German descent.[50] Reportedly, it had about 20,000 adherents.[48]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d Tenorio, Rich (September 30, 2023). "Fascism in America: a long history that predates Trump". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- ^ Fergus Bordewich. (2023). Klan War: Ulysses S Grant and the Battle to Save Reconstruction. Penguin Random House

- ^ "The Untold Story of Grant vs. the KKK: A Deep Dive with Historian Fergus M. Bordewich". YouTube. November 17, 2023. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ^ Bullard, Sara (1998). The Ku Klux Klan: A History of Racism and Violence. DIANE Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-7881-7031-7. Retrieved August 1, 2024.

one of the nation's first terrorist groups

- ^ Jacobs, David; O'Donnell, Patrick (2006). Ku Klux Klan: America's First Terrorists Exposed : the Rebirth of the Strange Society of Blood and Death. 8: Idea Men Productions.

Historians have suggested a combination of reasons for the eventual decline of the Ku Klux Klan of the Reconstruction period: 1)growth of public sentiment in the South against activities of masked terrorists

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Chalmers 1987, p. 322.

- ^ Amann, Peter H. (1986). "A 'Dog in the Nighttime' Problem: American Fascism in the 1930s". The History Teacher. 19 (4): 562. doi:10.2307/493879. JSTOR 493879.

- ^ "Ku Klux Klan Established". Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1855–1865. Digital History, Kansas City Public Library. Archived from the original on January 26, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2023.

- ^ "See the rise of the KKK in the U.S., 1915–1940". Mapping the Second Ku Klux Klan, 1915–1940. Archived from the original on October 13, 2016. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ^ Chomsky 2003, p. 46.

- ^ John P. Diggins, Mussolini and Fascism: The View from America (Princeton University Press, 1972).

- ^ Francesca De Lucia, "The Impact of Fascism and World War II on Italian-American Communities." Italian Americana 26.1 (2008): 83–95 online.

- ^ a b Chomsky 2003, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Victor C. Ferkiss, "Ezra Pound and American Fascism." Journal of politics 17.2 (1955): 173–197.

- ^ a b Michael E. Birdwell (2001). Celluloid Soldiers. p. 45.

- ^ a b Perlstein, Rick (April 11, 2017). "I Thought I Understood the American Right. Trump Proved Me Wrong". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- ^ Amann, Peter H. (1983). "Vigilante Fascism: The Black Legion as an American Hybrid". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 25 (3): 491. doi:10.1017/S0010417500010550. JSTOR 178625. S2CID 143477268.

- ^ Red Scare or Red Menace? American Communism and Anticommunism in the Cold War Era. p. 20.

- ^ Programming, Station (June 23, 2016). ""Terror In The City Of Champions" Explores Violence in Depression-Era Detroit". WDET 101.9 FM. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- ^ "Declared Organization Doomed". The New York Times. Associated Press. May 31, 1936. p. 10.

- ^ "Black Legion convictions". The Escanaba Daily Press. May 12, 1937. p. 10. Retrieved December 14, 2023.

- ^ a b Stanley G. Payne (2001). A History of Fascism 1914–45. pp. 350–1.

- ^ New York Times obituary, January 27, 2005, accessed March 16, 2022

- ^ a b Diamond, Sander A. (1970). "The Years of Waiting: National Socialism in the United States, 1922–1933". American Jewish Historical Quarterly. 59 (3): 256–271. ISSN 0002-9068. JSTOR 23877858. Archived from the original on February 12, 2023. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

- ^ Taylor, Alan. "American Nazis in the 1930s – The German American Bund". www.theatlantic.com. Archived from the original on September 25, 2023. Retrieved November 18, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "American Bund – The Failure of American Nazism: The German-American Bund's Attempt to Create an American 'Fifth Column'. Traces. Retrieved May 2nd 2019". Archived from the original on December 11, 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

- ^ "What Is the History of Fascism in the United States?". The Nation. January 17, 2024.

- ^ Friedman, John S. (March 8, 2001). "Kodak's Nazi Connections". ISSN 0027-8378. Archived from the original on April 10, 2021. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

- ^ "American Bund – The Failure of American Nazism: The German-American Bund's Attempt to Create an American 'Fifth Column'. Traces. Retrieved May 2nd 2019". Archived from the original on December 11, 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

- ^ Bell, Leland V. (1970). "The Failure of Nazism in America: The German American Bund, 1936-1941". Political Science Quarterly. 85 (4): 585–599. doi:10.2307/2147597. JSTOR 2147597.

- ^ a b Van Ells, Mark D. (August 2007). "Americans for Hitler – The Bund". America in WWII. pp. 44–49. Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- ^ "German-American Bund". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- ^ a b c Bell, Leland V. (1970). "The Failure of Nazism in America: The German American Bund, 1936–1941". Political Science Quarterly. 85 (4): 585–599. doi:10.2307/2147597. JSTOR 2147597. Archived from the original on October 8, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2022.

- ^ Patricia Kollander; John O'Sullivan (2005). "I must be a part of this war": a German American's fight against Hitler and Nazism. Fordham Univ Press. p. 37. ISBN 0-8232-2528-3.

- ^ "Nazis Hail George Washington as First Fascist". Life. March 7, 1938. p. 17. Retrieved November 25, 2011.

- ^ "Bund Activities Widespread. Evidence Taken by Dies Committee Throws Light on Meaning of the Garden Rally". The New York Times. February 26, 1939. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

Disorders attendant upon Nazi rallies in New York and Los Angeles this week again focused attention upon the Nazi movement in the United States and inspired conjectures as to its strength and influence.

- ^ "When Nazis Rallied at Madison Square Garden". WNYC Archives. Event occurs at 1:05:54. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

...and in our political life, where a Henry Morgenthau takes the place of men like Alexander Hamilton, and a Frank D. Rosenfeld takes the place of a George Washington.

- ^ Buder, Emily (October 10, 2017). "When 20,000 American Nazis Descended Upon New York City". The Atlantic. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

In 1939, the German American Bund organized a rally of 20,000 Nazi supporters at Madison Square Garden in New York City.

- ^ Piper, Michael Collins, and Ken Hoop. "A Mockery of Justice—The Great Sedition Trial of 1944." The Barnes Review 5 (1999): 5–20 online.

- ^ a b c d Schiessl, Christoph. Alleged Nazi Collaborators in the United States after World War II. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2016.

- ^ Lichtblau, Eric (November 13, 2010). "Nazis Were Given 'Safe Haven' in U.S., Report Says". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 17, 2023. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ "The Danish Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies". November 9, 2007. Archived from the original on November 9, 2007. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ a b "Neo-Nazism". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Archived from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ a b "Neo-Nazi". Southern Poverty Law Center. Archived from the original on February 12, 2021. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ a b "Killer of American Nazi Chief Paroled". St. Joseph News-Press. August 23, 1975. Retrieved December 3, 2021.

- ^ Rockwell, George Lincoln. From Ivory Tower to Privy Wall: On The Art of Propaganda Archived August 3, 2014, at the Wayback Machine c.1966

- ^ Potok, Mark (August 29, 2001). "The Nazi International". Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- ^ a b Green & Stabler 2015, p. 390.

- ^ Wolter & Masters 2004, p. 65.

- ^ Van Ells, Mark D. (2007). "Americans for Hitler – The Bund". America in WWII. Vol. 3. pp. 44–49. Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- ^ a b c "National Alliance For Law Enforcement". Anti-Defamation League. Retrieved August 31, 2017.Hilliard, Robert L.; Michael C. Keith (1999). Waves of Rancor: Tuning into the Radical Right. M. E. Sharpe. p. 165. ISBN 978-0765601315.

- ^ Quarles, Chester A. (1999). The Ku Klux Klan and Related American Racialist and Antisemitic Organizations: A History and Analysis. McFarland. p. 146. ISBN 978-0786406470.

- ^ Richie, Warren (December 20, 2011). "Failed Martin Luther King Day parade bomber gets 32-year sentence". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ^ "Bomb suspect tied to supremacist group". Boston Globe. March 10, 2011. Archived from the original on September 9, 2011. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ^ a b "National Alliance". Southern Poverty Law Center. Archived from the original on February 21, 2021. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ "William Pierce: A Political History". Southern Poverty Law Center. Winter 1999. Archived from the original on July 13, 2007. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- ^ Darby, Seward (March 31, 2021). "The father, the son and the racist spirit: being raised by a white supremacist". The Guardian.

- ^ "Atomwaffen Division". Southern Poverty Law Center. Archived from the original on December 2, 2019. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ Berlet, Chip; Vysotsky, Stanislav (2006). "Overview of U.S. White Supremacist Groups". Journal of Political & Military Sociology. 34 (1): 24. ISSN 0047-2697. JSTOR 45294185.

- ^ Blout, Emily; Burkart, Patrick (January 4, 2021). "White Supremacist Terrorism in Charlottesville: Reconstructing 'Unite the Right'". Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. 46 (9): 1624–1652. doi:10.1080/1057610X.2020.1862850. ISSN 1057-610X. S2CID 234176136.

- ^ a b "The National Socialist Movement". www.adl.org. Retrieved April 5, 2024.

- ^ a b "National Socialist Movement". Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ^ "The Nationalist Front Limps into 2017". Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- ^ Haag, Matthew (July 21, 2018). "'White Civil Rights Rally' Planned Near White House by Charlottesville Organizer". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 20, 2019. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ Lind, Dara (August 12, 2017). "Unite the Right, the violent white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, explained". Vox. Archived from the original on August 13, 2017.

- ^ a b Thrush, Glenn; Haberman, Maggie (August 15, 2017). "Trump Gives White Supremacists an Unequivocal Boost". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 16, 2017.

- ^ Alridge, Derrick P. (October 20, 2017). "The Events of August 11th and 12th: A Historian's Brief Reflections on Charlottesville". alumni.virginia.edu. University of Virginia. Archived from the original on September 12, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ a b Fausset, Richard; Feuer, Alan (August 13, 2017). "Far-Right Groups Surge Into National View In Charlottesville". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 16, 2017.

- ^ "Charlottesville: One killed in violence over US far-right rally". BBC News. August 13, 2017. Archived from the original on September 10, 2019.

- ^ "Neo-Nazi Jason Kessler Lives With Parents, Gets Scolded By Dad During Livestream". HuffPost. August 16, 2018. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

- ^ McDermott, Stephen (August 16, 2018). "'Get out of my room': 35-year-old neo-Nazi censured by father in livestream with fellow white supremacist". TheJournal.ie. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

- ^ "Jason Kessler's anti-Jewish screed was interrupted by his father: 'Hey, you get out of my room'". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on March 12, 2023. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

- ^ Spellings, Sarah (May 22, 2017). "White Nationalist Richard Spencer Loses Gym Membership After Being Confronted". The Cut. Archived from the original on December 29, 2019. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

- ^ a b Stapley, Garth (August 14, 2017). "'This is a huge victory.' Oakdale white supremacist revels after deadly Virginia clash". The Modesto Bee. Archived from the original on August 15, 2017. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ Weill, Kelly (March 27, 2018). "Neo-Confederate League of the South Banned From Armed Protesting in Charlottesville". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on October 20, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- ^ Gunter, Joel (August 13, 2017). "A reckoning in Charlottesville". BBC News. Archived from the original on May 5, 2019. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

- ^ Kelkar, Kamala (August 12, 2017). "Three dead after white nationalist rally in Charlottesville". PBS NewsHour. Archived from the original on May 14, 2018. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- ^ Wootson, Cleve R. Jr. (August 13, 2017). "Here's what a neo-Nazi rally looks like in 2017 America". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 19, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- ^ Park, Madison (August 12, 2017). "Why white nationalists are drawn to Charlottesville". CNN. Archived from the original on August 12, 2017. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

- ^ Early, John, ed. (May 16, 2018). "3 Militia Groups Connected to Unite the Right Rally Settle Lawsuits". nbc29.com. WVIR-TV. Archived from the original on February 14, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- ^ "Deconstructing the symbols and slogans spotted in Charlottesville". The Washington Post. August 18, 2017. Archived from the original on August 20, 2017. Retrieved November 20, 2018.

- ^ "Flags and Other Symbols Used By Far-Right Groups in Charlottesville". Hatewatch. Southern Poverty Law Center. August 12, 2017. Archived from the original on August 13, 2017.

- ^ a b Heim, Joe; Silverman, Ellie; Shapiro, T. Rees; Brown, Emma (August 13, 2017). "One dead as car strikes crowds amid protests of white nationalist gathering in Charlottesville; two police die in helicopter crash". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 13, 2017.

- ^ Green, Emma (August 15, 2017). "Why the Charlottesville Marchers Were Obsessed With Jews". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on August 17, 2017.

- ^ [66][68][81][82][31][83][84]

- ^ Stolberg, Sheryl Gay; Rosenthal, Brian M. (August 12, 2017). "Man Charged After White Nationalist Rally in Charlottesville Ends in Deadly Violence". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 12, 2017. Retrieved August 13, 2017.

- ^ Franklin, Sekou (June 1, 2020). "Charlottesville 2017: The Legacy of Race and Inequity". Journal of American History. 107 (1): 275–277. doi:10.1093/jahist/jaaa165. ISSN 0021-8723. Archived from the original on July 10, 2022. Retrieved June 29, 2022 – via Oxford Academic.

- ^ Multiple sources:

- "Vanguard America (Patriot Front, American Vanguard) - Extremist Watch". extremistwatch.org. Archived from the original on December 24, 2017. Retrieved December 23, 2017.

- "Patriot Front". Southern Poverty Law Center. Archived from the original on December 22, 2018. Retrieved February 12, 2020.

- "Patriot Front". Anti-Defamation League. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved February 12, 2020.

- ^ "Patriot Front". ADL. Archived from the original on December 23, 2017. Retrieved December 23, 2017.

- ^ "Meet 'Patriot Front': Neo-Nazi network aims to blur lines with militiamen, the alt-right". Southern Poverty Law Center. Archived from the original on December 23, 2017. Retrieved December 23, 2017.

- ^ Roman, Gabriel San (December 13, 2017). "New Fascist Group Appeared at Laguna Beach Anti-Immigrant Rally". OC Weekly. Archived from the original on December 24, 2017. Retrieved December 23, 2017.

- ^ McNamara, Neal (November 20, 2017). "White Nationalist Group Targets Bellevue, Gig Harbor". Bellevue, WA Patch. Archived from the original on December 24, 2017. Retrieved December 23, 2017.

- ^ "Trump told chief of staff Hitler 'did a lot of good things', book says". the Guardian. July 7, 2021.

- ^ Yang, Maya (March 4, 2022). "US white supremacist propaganda was at historically high levels in 2021". The Guardian. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ^ Kagan, Robert (May 18, 2016). "This is how fascism comes to America". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ McGaughey, Ewan (2018). "Fascism-Lite in America (or the Social Ideal of Donald Trump)". British Journal of American Legal Studies. 7 (2): 291–315. doi:10.2478/bjals-2018-0012. S2CID 195842347. SSRN 2773217.

- ^ Stanley, Jason (October 15, 2018). "If You're Not Scared About Fascism in the U.S., You Should Be". The New York Times. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ Snyder, Timothy (October 30, 2018). "Donald Trump borrows from the old tricks of fascism". The Guardian. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ Gordon, Peter (January 7, 2020). "Why Historical Analogy Matters". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ Szalai, Jennifer (June 10, 2020). "The Debate Over the Word Fascism Takes a New Turn". The New York Times. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ Cummings, William; Garrison, Joey; Sergent, Jim (January 6, 2021). "By the numbers: President Donald Trump's failed efforts to overturn the election". USA Today. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ Matthews, Dylan (January 14, 2020). "The F Word: The debate over whether to call Donald Trump a fascist, and why it matters". Vox. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ Nichols, Bradley; Guettel, Jens-Uwe; Hake, Sabine; Kucik, Emanuela; Stern, Alexandra Minna; Wiesen, S. Jonathan (2022). "A Reusable Past: The Meaning of the Third Reich in Recent U.S. Discourse". Central European History. 55 (4): 551–575. doi:10.1017/S0008938922001364. ISSN 0008-9389.

- ^ Kerr, Anne; Wright, Edmund (2015). "Munich 'beer-hall' putsch". A Dictionary of World History (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-968569-1. Retrieved September 21, 2024.

- ^ Trump and the legacy of a menacing past. Giroux, Henry A., Cultural Studies, 09502386, July 2019, Vol. 33, Issue 4

- ^ Rosenfeld, Gavriel D. (2019). "An American Führer? Nazi Analogies and the Struggle to Explain Donald Trump". Central European History. 52 (4): 554–587. doi:10.1017/S0008938919000840. ISSN 0008-9389. JSTOR 26870257. S2CID 212950934.

- ^ "The neo-fascist discourse and its normalisation through mediation". By: Cammaerts, Bart, Journal of Multicultural Discourses, 17447143, Sep2020, Vol. 15, Issue 3

- ^ Homans, Charles (October 21, 2020). "Donald Trump's Strongman Act, and Its Limits". The New York Times.

- ^ Tirabassi, Maddalena (1984–1985). "Enemy Aliens or Loyal Americans?: the Mazzini Society and the Italian-American Communities". Rivista di Studi Anglo-Americani (4–5): 399–425.

- ^ Morrow, Felix (June 1943). "Washington's Plans for Italy". Fourth International. 4 (6): 175–179. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ Premature antifascists and the Post-war world Archived 31 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives Bill Susman Lecture Series. King Juan Carlos I of Spain Center at New York University, 1998. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ Knox, Bernard (Spring 1999). "Premature Anti-Fascist". Antioch Review. 57 (2): 133–149. doi:10.2307/4613837. JSTOR 4613837.

- ^ John Nichols (October 26, 2009). "Clarence Kailin: 'Premature Antifascist' – and proudly so". Cap Times. Capital Times (Madision, Wisconsin). Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- ^ Haynes, John Earl; Klehr, Harvey (2005). In Denial: Historians, Communism & Espionage. San Francisco: Encounter Books. p. 123. ISBN 978-1594030888. Retrieved March 22, 2014.

- ^ Beinart, Peter (August 16, 2017). "What Trump Gets Wrong About Antifa". The Atlantic. Retrieved August 16, 2017.

- ^ Stein, Perry (August 16, 2017). "Anarchists and the antifa: The history of activists Trump condemns as the 'alt-left'". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ^ Snyders, Matt (February 20, 2008). "Skinheads at Forty". City Pages. Archived from the original on August 3, 2012. Retrieved July 29, 2012.

- ^ Bray, Mark (August 16, 2017). "Who are the antifa?". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ^ Bogel-Burroughs, Nicholas (July 2, 2019). "What Is Antifa? Explaining the Movement to Confront the Far Right". The New York Times. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ a b Sacco, Lisa N. (June 9, 2020). "Are Antifa Members Domestic Terrorists? Background on Antifa and Federal Classification of Their Actions InFocus IF10839". Congressional Research Service. Retrieved September 9, 2020. Updated June 9, 2020.

- ^ Bogel-Burroughs, Nicholas; Garcia, Sandra E. (September 28, 2020). "What Is Antifa, the Movement Trump Wants to Declare a Terror Group?". The New York Times. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

One of the first groups in the United States to use the name was Rose City Antifa, which says it was founded in 2007 in Portland.

- ^ "One America - Northwest Coalition Against Malicious Harassment". The White House. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ Enzinna, Wes (April 27, 2017). "Inside the Underground Anti-Racist Movement That Brings the Fight to White Supremacists". Mother Jones. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- ^ Strickland, Patrick (February 21, 2017). "US anti-fascists: 'We can make racists afraid again'". Al-Jazeera. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- ^ Lennard, Natasha (January 19, 2017). "Anti-Fascists Will Fight Trump's Fascism in the Streets". The Nation. Archived from the original on August 15, 2017. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- ^ Clarke, Colin; Kenney, Michael (June 23, 2020). "What Antifa Is, What It Isn't, and Why It Matters". War on the Rocks. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

[...] Antifa, a highly decentralized movement of anti-racists who seek to combat neo-Nazis, white supremacists, and far-right extremists whom Antifa's followers consider 'fascist' [...].

- ^ "Designating Antifa as Domestic Terrorist Organization Is Dangerous, Threatens Civil Liberties". Southern Poverty Law Center. June 2, 2020. Retrieved September 8, 2020.

- ^ Kaste, Martin; Siegler, Kirk (June 16, 2017). "Fact Check: Is Left-Wing Violence Rising?". NPR.org. NPR. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ Maida, Adam (January 16, 2018). "Meet Antifa's Secret Weapon Against Far-Right Extremists". Wired. Retrieved November 13, 2018.

- ^ Beauchamp, Zack (June 8, 2020). "Antifa, explained". Vox. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ a b Lois, Beckett (July 27, 2020). "Anti-fascists linked to zero murders in the US in 25 years". The Guardian.

- ^ Jones, Seth G. (June 4, 2020). "Who Are Antifa, and Are They a Threat?". Center for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ Pasley, James. "Trump frequently accuses the far-left of inciting violence, yet right-wing extremists have killed 329 victims in the last 25 years, while antifa members haven't killed any, according to a new study". Business Insider. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ Swan, Betsy Woodruff (September 4, 2020). "DHS draft document: White supremacists are greatest terror threat". Politico. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ "A Fake Antifa Account Was 'Busted' for Tweeting from Russia". Vice News. September 28, 2017. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ^ "Far-right smear campaign against Antifa exposed by Bellingcat". BBC. August 24, 2017. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

- ^ Feldman, Brian (August 21, 2017). "How to Spot a Fake Antifa Account". New York. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ Glaun, Dan (September 14, 2017). "Fake Boston Antifa group, which claimed credit for anti-racism banner at Red Sox game, is actually run by right wing trolls". The Republican. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ Feuer, Alan; Goldman, Adam; MacFarquhar, Neil (June 11, 2020). "Federal Arrests Show No Sign That Antifa Plotted Protests". The New York Times. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

Despite claims by President Trump and Attorney General William P. Barr, there is scant evidence that loosely organized anti-fascists are a significant player in protests. [...] A review of the arrests of dozens of people on federal charges reveals no known effort by antifa to perpetrate a coordinated campaign of violence. Some criminal complaints described vague, anti-government political leanings among suspects, but a majority of the violent acts that have taken place at protests have been attributed by federal prosecutors to individuals with no affiliation to any particular group.

- ^ Peiser, Jaclyn (August 10, 2020). "'Their tactics are fascistic': Barr slams Black Lives Matter, accuses the left of 'tearing down the system'". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- ^ Haberman, Maggie; Savage, Charlie (May 31, 2020). "Trump, Lacking Clear Authority, Says U.S. Will Declare Antifa a Terrorist Group". The New York Times. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ Perez, Evan; Hoffman, Jason (May 31, 2020). "Trump tweets Antifa will be labeled a terrorist organization but experts believe that's unconstitutional". CNN. CNN. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ Bray, Mark (June 1, 2020). "Antifa isn't the problem. Trump's bluster is a distraction from police violence". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

Sources

[edit]- Chalmers, David M. (1987). Hooded Americanism: The History of the Ku Klux Klan. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. p. 512. ISBN 978-0822307303.

- Chomsky, Noam (2003). Hegemony or survival : America's quest for global dominance. Henry Holt and Company, LLC. ISBN 0-8050-7400-7.

- Green, Michael S.; Stabler, Scott L. (2015). Ideas and Movements that Shaped America: From the Bill of Rights to "Occupy Wall Street" (3 vols.). Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 390. ISBN 978-1610692519. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- Wolter, Erik V.; Masters, Robert J. (2004). Loyalty On Trial: One American's Battle With The FBI. New York: iUniverse. p. 65. ISBN 978-0595327034.

Further reading

[edit]- Roberto, M. J. (2018). The Coming of the American Behemoth: The Origins of Fascism in the United States, 1920 -1940. NYU Press.

- Rosenfeld, G. D.; Ward, J., ed. (2023). Fascism in America: Past and Present. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781009337465.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link)