Admiralty chart

Admiralty charts are nautical charts issued by the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office[1] (UKHO) and subject to Crown Copyright. Over 3,500 Standard Nautical Charts (SNCs) and 14,000 Electronic Navigational Charts (ENCs) are available with the Admiralty portfolio offering the widest official coverage of international shipping routes and ports, in varying detail.

Admiralty charts have been produced by UKHO for over 200 years, with the primary aim of saving and protecting lives at sea. The core market for these charts includes over 40,000 defence and merchant ships globally. Today, their products are used by over 90% of ships trading internationally.

History

[edit]The British admiralty charts are compiled, drawn and issued by the Hydrographic Office. This department of the Admiralty was established under Earl Spencer by an order in council in 1795, consisting of the Hydrographer, Alexander Dalrymple, one assistant and a draughtsman. The initial remit was to organise the charts and information in the office, and to make it available to His Majesty's ships.[2]: 101

Chart design and production

[edit]The Hydrographic Department began printing charts in 1800, with the acquisition of its first printing press.[3] Initially charts were produced only for use by the Navy, but in 1821, Thomas Hurd, who had succeeded Dalrymple as Hydrographer in 1808, persuaded the Admiralty to allow sales to the public.[4]: 27 [5]: 105–106 The first catalogue of Admiralty charts was published in 1825, and listed 756 charts.[6]

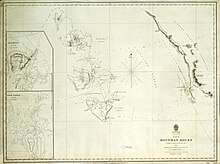

Charts were printed from copper plates. Plates were engraved, in reverse, with a burin. The plate was inked, and the excess ink wiped from the flat surface before printing, so that ink remained only in the engraved lines (intaglio printing). The process allowed very fine detail to be printed, but was slow. When corrections or alterations were needed to a chart, the copper was hammered from behind, the raised section scraped and smoothed, and the new information engraved on the smoothed area.[7]: 426 This allowed plates to continue in use for long periods, in some cases for over a hundred years.

Charts often showed a great deal of detail of features on land as well as sea. Depths were shown by individual soundings while hills and mountains were shown by hatch marks. Printing was in black and white, but some charts were hand-coloured, either to emphasise water depth or terrain, or to indicate specific features such as lighthouses.

Experiments were made with the use of lithography from the 1820s, but results were not entirely satisfactory. Lithography was less expensive, and some charts were printed in this way, but printing from copper plates continued to be the main method into the 20th-Century, and in both cases from flat-bed printing machines.[8]: 10 [9] The most common chart size was early established as the "Double-elephant", about 39 X 25.5 inches, and this has continued to be the case.[10] Chart design gradually simplified over the years, with less detail on land, focusing on features visible to the mariner. Contours were increasingly used for hills instead of hatching.

All printing of Admiralty charts was carried out in England until the first World War. In 1915, the survey ship HMS Endeavour was sent to support the Gallipoli campaign, and carried printing equipment so that charts from her surveys could be rapidly made available to the fleet. In 1938 trials were made with the rotary offset process, using a zinc plate copied from the copper original. These were successful, and by the outbreak of World War II all chart production used this process, which was faster, and reduced wear and tear on the copper original. This development was crucial in meeting the increased wartime demand for charts.[8]: 81 During World War II the distribution of printing facilities was on a much larger scale than previously. There was also concern about the safety of the original printing plates in the event of air raids, and high quality baryta paper proofs were made as backups.[8]: 119

From the late 1940s, developments in printing technology made colour printing possible with sufficient accuracy for chart work. The first use of printed (as opposed to hand-drawn) colour was in marking of water depths. Solid pale blue was used for water to the 3 fathom line, and a ribbon of blue for six fathoms.[11]

Metrication of Admiralty charts began in 1967, and it was decided to synchronise this with the introduction of a new style of chart, with increased use of colour, which continues in use today. The most striking change is the use of buff for land. Green is used for drying (intertidal) areas, and magenta to indicate lights and beacons. Thus the chart coloration gave a clear indication to users as to whether they were using a chart with depths in fathoms or feet. While depths and heights were in metres, the nautical mile continued to be an international standard. Derived from the length of 1 minute of latitude, it is defined as 1852 metres.[12][13][14][15]

Surveying

[edit]Initially, surveys and explorations continued to be commissioned directly by the Admiralty, for example Flinders' circumnavigation of Australia in 1801–3, [5]: 75–91 and Beaufort's survey of the southern coast of Turkey (then called Karamania) in 1811–1812.[16] Under Hurd, the Hydrographic Office became more involved in surveying work, and by 1817 there were three vessels specifically assigned to the surveying service, HMS Protector, HMS Shamrock, and HMS Congo.[4]: 26–29 This continued, particularly under Francis Beaufort, Hydrographer from 1829 to 1855.[5]: 189–199

Over the following century the surveying service expanded in both size and reach, becoming a global operation. Several accounts record this history in detail. Llewellyn Styles Dawson was a surveyor particularly noted for his work in China (1865-1870) and a naval assistant in the department for five years (1876-1881).[4]: 151–152 During the latter period he commenced work on the two-volume Memoirs of Hydrography which described the Royal Navy's surveying activities between 1750 and 1885, and presented biographies of the officers involved in the activities.[17] The history was continued to 1917 by Archibald Day, Hydrographer from 1950 to 1955 in his The Admiralty Hydrographic Service from 1795-1919, explicitly described as a continuation of Dawson's Memoirs.[4]: 5–6 Thomas Henry Tizard published a chronological list of the officers and vessels conducting British maritime discoveries and surveys until 1900.[18] These works are all in the public domain. Roger Morris, Hydrographer from 1985 to 1990, published Charts and Surveys in Peace and War 1919-1970, a further continuation of Memoirs.[8] A less formal account of British Naval Hydrography in the 19th-Century is given by Steve Ritchie, Hydrographer 1966–1971, in The Admiralty Chart.[5] Tony Rice has produced a listing and description of the vessels involved in surveying and oceanographic work from 1800 to 1950.[19]

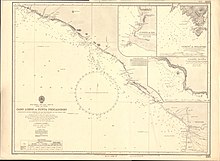

A number of major overseas surveys were completed in the years to 1855, a period dominated by Francis Beaufort, Hydrographer from 1829 to 1855. Owen carried out his survey of East Africa from the Cape of Good Hope to Cape Guardafui on the Horn of Africa in 1822–1825, an operation that cost the lives of more than half of the crew due to tropical illness.[5]: 107–135 The second voyage of the Beagle to South America (1831-6) is mostly famous for the scientific importance of Darwin's observations and collections, but Captain Robert Fitzroy's surveys of the coast of South America from the River Plate to Ecuador via the Straits of Magellan have been described as a "monumental achievement",[16]: 255 and as "opening up the South American continent to European trade".[5]: 220 Thomas Graves was working in the Mediterranean from 1836 to 1850. Like a number of surveyors before and since, he explored the antiquities and natural history of the numerous places he charted.[5]: 269 In 1841-7 Edward Belcher was engaged in the Far East, including making the first survey of Hong Kong.[5]: 221–237 The longest running survey was that of Bayfield, whose survey of the Canadian coasts, the St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes occupied him from 1816 to 1856.[20]

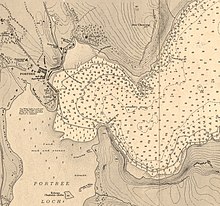

Surveys in home waters were also important. What Robinson (1962) described as the "Grand Survey of the British Isles" began with the appointment of George Thomas as Head Maritime surveyor. Thomas and a series of able surveyors including Michael Slater, Henry Otter, Charles Robinson, William Hewett and Frederick Beechey surveyed the coasts of Britain and Ireland over the next 30 years. Thomas developed techniques for extending triangulation over the shallow waters of the Thames Estuary and the southern part of the North Sea, allowing the exact positions of treacherous sand banks to be determined for the first time.[2]: 127–142 These surveys added large numbers of new charts, as well as improvements to old ones. By 1855, when Beaufort retired, the survey of the coasts of the United Kingdom was complete,[5]: 248 and there were about 2,000 charts in the catalogue, covering all the oceans of the world.[7]: 426

An important survey in 1870 was the Suez Canal. Britain had remained aloof in the early stages of the project, believing it to be impracticable. When the canal was nearing completion, the question arose as to its suitability for naval ships. George Nares in HMS Newport traversed the canal in both directions taking soundings and making measurements, and also surveyed the approaches. This led to the canal becoming an established route for the Royal Navy. [5]: 317–319 [4]: 82

As well as the "grand surveys" much detailed work was needed. A particular concern was finding isolated rocks. These were easily missed by soundings with lead and line, which did not give any information about the depths between the soundings.[21] In 1887, two ships were lost in the southern Red Sea, fortunately without loss of life, after striking an uncharted reef close to a major shipping lane. Several attempts to find this were made before HMS Stork found it (and nearly struck it) in 1888. It was named Avocet Rock after the first ship to strike it.[22][4]: 143 [23]

Technical developments over the years improved surveying methods and the accuracy of the charts. For depth determination, methods of measuring depth from a moving ship were developed, as well as "sweeping", dragging a horizontal line across an area to detect hazards that might be missed by individual soundings.[24] Echo sounding was introduced in the 1920s, and Percy Douglas, hydrographer from 1924 to 1932, was a strong advocate of this method. As well as increasing productivity, it enabled continuous monitoring along a sounding line, reducing the chance of a hazard being missed.[25][26] Isolated rocks between sounding lines could still be missed, and it was not until the development of sideways-looking sonar in the 1960s and 70s that this risk could be eliminated.[23]

Features of modern charts

[edit]Most navigation today uses GPS chart plotters with electronic charts. Paper charts continue to be issued, and are valuable for passage planning and course plotting.

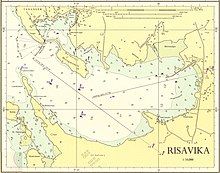

The scale of the charts can vary according to purpose; large-scale charts often cover approaches to harbours, such as Port Approach Guides, medium-scale charts often cover frequently used coastal areas, and small-scale charts are regularly used for navigation in more open areas. A series of small craft charts are also available at suitable scales.[27][28]

Admiralty charts include information on: depths (chart datum), coastline, buoyage, land and underwater contour lines, seabed composition, hazards, tidal information (indicated by "tidal diamonds"), prominent land features, traffic separation schemes radio direction finding (RDF) information, lights, and other information to assist in navigation.[28]

Navigation charts at a scale of 1:50,000 or smaller (1:100,000 is a smaller scale than 1:50,000) use the Mercator projection, and have since at least the 1930s.[29][30] The Mercator projection has the property of maintaining angles correctly, so that a line on the earth's surface that crosses all the meridians at the same angle (a rhumb line) will be represented on the chart by a straight line at the same angle. Thus if a straight line is drawn on the chart from A to B, and the angle determined, the ship may sail at a constant bearing at that angle to reach B from A. Allowances for magnetic variation and magnetic deviation must also be made. However, a rhumb line is not in general the shortest distance between two points, which is a great circle. (The equator and lines of longitude are both great circles and rhumb lines.) When navigating over longer distances the difference becomes important, and charts using the gnomonic projection, on which all great circles are shown as straight lines, are used for course planning.[30] In the past, the gnomonic projection was widely used for navigation charts, and also for polar charts.[29]

Since the late 1970s, all charts at a scale of 1:50,000 or larger have used the transverse Mercator projection,[30] which is the projection used for the Ordnance Survey National Grid. Topography on Admiralty charts of the UK is generally based on Ordnance Survey mapping. For the small areas depicted on such maps, the differences between projections are of no practical importance.[30]

Admiralty charts are issued by the UKHO for a variety of users; Standard Nautical Charts (SNCs) are issued to mariners subject to the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) convention, while chart folios, at a convenient A2 size, are produced for leisure users.[28] Alongside its paper charts, UKHO produces an expanding range of digital products to fulfil the impending compulsory carriage requirements of ECDIS/ENCs, as issued by the International Maritime Organization (IMO).

The digital range comprises Electronic Navigational Charts (ENCs) for use with an Electronic Chart Display and Information System (ECDIS), which can be displayed and interrogated through Admiralty Vector Chart Service (AVCS).[27] The range also includes Admiralty Raster Chart Service (ARCS), which allows paper nautical charts to be viewed in raster form on an ECDIS.[28]

Due to the changing nature of the seabed and other charted features, chart information must be up-to-date to maintain accuracy and general safety. This is ensured by UKHO continually assessing hydrographic data for vital safety information, with urgent updates issued via weekly Notices to Mariners (NMs)

See also

[edit]- Hydrography

- Hydrographic survey

- Nautical chart

- United Kingdom Hydrographic Office

- List of survey vessels of the Royal Navy

- Vertical Offshore Reference Frames

References

[edit]- ^ UK Hydrographic Office

- ^ a b Robinson, Adrian Henry Wardle (1962). Marine Cartography in Britain: A History of the Sea Chart to 1855. With a Foreword by Sir John Edgell. Leicester University Press. OCLC 62431872.

- ^ David, Andrew (2008). Liebenberg, Elri; Demhardt, Imre Josef; Collier, Peter (eds.). The emergence of the Admiralty Chart in the nineteenth century. International Cartographic Association. pp. 1–16. ISBN 9780620437509.

- ^ a b c d e f Day, Archibald (1967). The Admiralty Hydrographic Service, 1795-1919. H.M. Stationery Office. OCLC 1082894797.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Ritchie, George Stephen (1967). The Admiralty Chart: British Naval Hydrography in the Nineteenth Century. Hollis & Carter. OCLC 1082888087.

- ^ A catalogue of charts, plans, and views, printed at the Admiralty Office, for the use of His Majesty's Navy; and now sold (wholesale and retail), for the use of navigators in general (PDF). London: Admiralty Office. 1825.

- ^ a b Morris, Roger (1996). "200 years of Admiralty charts and surveys". The Mariner's Mirror. 82 (4): 420–435. doi:10.1080/00253359.1996.10656616.

- ^ a b c d Morris, Roger O. (1995). Charts and Surveys in Peace and War: The History of the Royal Navy's Hydrographic Service, 1919-1970. H.M. Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0-11-772456-3.

- ^ Webb, Adrian James (2010). The Expansion of British Naval Hydrographic Administration, 1808-1829 (PhD). University of Exeter. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Conference of Commonwealth Survey Officers 1971: Report of Proceedings, Volume 2. H.M. Stationery Office. 1973. OCLC 35494232.

- ^ Magee, G.A. (1968). "The Admiralty Chart: Trends in Content and Design". The Cartographic Journal. 5 (1): 28–33. Bibcode:1968CartJ...5...28M. doi:10.1179/caj.1968.5.1.28.

- ^ Ritchie, Rear Admiral G. S. (June 1971). "The Work of the Hydrographic Department". The Cartographic Journal. 8 (1): 9–12. Bibcode:1971CartJ...8....9R. doi:10.1179/caj.1971.8.1.9. eISSN 1743-2774. ISSN 0008-7041.

- ^ Magee, G. A. (1 September 1978). "The New-Look Admiralty Chart". Journal of Navigation. 31 (3): 419–422. doi:10.1017/S0373463300048864. eISSN 1469-7785. ISSN 0373-4633. S2CID 128443157.

- ^ Great Britain. Navy Department (1997). Admiralty Manual of Navigation: BR 45(1), Volume 1. The Stationery Office. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-11-772880-6. OCLC 1055107257.

- ^ "Admiralty Maritime Data Solutions". UK Hydrographic Office. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ a b Friendly, Alfred (1977). Beaufort of the Admiralty: The Life of Sir Francis Beaufort, 1774-1857. Hutchinson. pp. 182–217. ISBN 978-0-09-128500-5.

- ^ Dawson, Llewellyn Styles (1885). Memoirs of hydrography, including brief biographies of the principal officers who have served in H.M. Naval Surveying Service between the years 1750 and 1885. Eastbourne: Henry W. Keay. Part 1. - 1750 to 1830; Part 2. - 1830-1885.

- ^ Chronological List of the Officers Conducting British Maritime Discoveries and Surveys: Together with the Names of the Vessels Employed from the Earlier Times Until 1900. Her Majesty's stationery office. 1900. OCLC 182997601.

- ^ Rice, A. L. (1986). British Oceanographic Vessels, 1800-1950. Ray Society. ISBN 978-0-903874-19-9.

- ^ "Admiral Henry Wolsey Bayfield". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 46 (4): 182–183. 12 February 1886. doi:10.1093/mnras/46.4.182. eISSN 1365-2966. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ Dobson, Richard (2002). "International Co-operation to Improve Safety of Navigation in the Southern Red Sea". The International Hydrographic Review. 3 (2): 35–44.

- ^ "The "Avocet" Rock". Nature. 38 (975): 222–224. July 1888. Bibcode:1888Natur..38..222.. doi:10.1038/038222a0. eISSN 1476-4687. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ a b Dobson, Richard (2002). "International Co-operation to Improve Safety of Navigation in the Southern Red Sea". The International Hydrographic Review. 3 (2): 35–44.

- ^ Helby, H.W.H. (1905). "Some Observations on Sounding, and the Admiralty Charts". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. 49 (2): 935–953. doi:10.1080/03071840509416605.

- ^ Special Publication No. 4: Echo Sounding (Report). International Hydrographic Bureau. 1925.

- ^ Douglas, H.P. (1929). "Echo Sounding". The Geographical Journal. 74 (1): 47–55. Bibcode:1929GeogJ..74...47D. doi:10.2307/1784944. JSTOR 1784944.

- ^ a b Tim Bartlett. RYA Navigation Handbook. Royal Yachting Association; 2nd edition (2014), 192 pag. ISBN 1906435944, ISBN 978-1906435943

- ^ a b c d Tom Cunliffe. The Complete Day Skipper: Skippering with Confidence Right From the Start. Adlard Coles; 5 edition (2016), 208 pag. ISBN 1472924169, ISBN 978-1472924162