Seychelles warbler

| Seychelles warbler | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Acrocephalidae |

| Genus: | Acrocephalus |

| Species: | A. sechellensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Acrocephalus sechellensis (Oustalet, 1877)

| |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Bebrornis sechellensis[2] | |

The Seychelles warbler (Acrocephalus sechellensis), also known as Seychelles brush warbler,[2] is a small songbird found on five granitic and corraline islands in the Seychelles. It is a greenish-brown bird with long legs and a long slender bill. It is primarily found in forested areas on the islands. The Seychelles warbler is a rarity in that it exhibits cooperative breeding, or alloparenting, which means that the monogamous pair is assisted by nonbreeding female helpers.

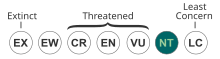

A few decades ago the Seychelles warbler was on the verge of extinction, with only 26 birds surviving on Cousin Island in 1968. Due to conservation efforts there are more than 2500 of the species alive today with viable populations on Denis, Frégate, Cousine and Aride Islands, as well as Cousin Island.[3]

Taxonomy and systematics

[edit]The Seychelles warbler is closely related to the Rodrigues warbler (Acrocephalus rodericanus) and the two species have sometimes been placed in their own genus, Bebrornis. The two species have also been considered allied to the Malagasy genus Nesillas. A 1997 study confirmed, however, that the two species were part of a clade of Afrotropical warblers within Acrocephalus that also includes the Madagascar swamp warbler, the greater swamp warbler, the lesser swamp warbler and the Cape Verde warbler.[4][5][6]

Description

[edit]The Seychelles warbler is a small, plain Acrocephalus warbler, between 13 and 14 cm (5.1–5.5 in) in length and with a wingspan of 17 cm (6.7 in).[7] It has long grey-blue legs, a long horn-coloured bill, and a reddish eye. Adults show no sexual dimorphism in their plumage. The back, wings, flanks and head are greenish-brown and the belly and breast are dirty white. The throat is a stronger white and there is a pale supercilium in front of the eye. Juvenile birds are darker with a more bluish eye.

The voice of the Seychelles warbler is described as rich and melodious,[7] similar to a human whistle. Its structure is simple and is composed of short song sequences delivered at a low frequency range.[8] The lack of a wide frequency range sets it apart from other species in its genus, such as the reed warbler, its song is similar to its closest relatives in Africa such as the greater swamp warbler.

Behaviour

[edit]The Seychelles warbler naturally occurs in dense shrubland and in tall forests of Pisonia grandis. It is almost exclusively an insectivore (99.8% of its diet is insects), and obtains 98% of its prey by gleaning small insects from the undersides of leaves. It does occasionally catch insects on the wing as well.[9] Most of the foraging occurs on Pisonia, Ficus reflexa and Morinda citrifolia.[10] Studies of the foraging behaviour found that Seychelles warblers favour Morinda and spend more time foraging there than in other trees and shrubs; the same study found that insect abundance is highest under the leaves of that shrub.[11] The planting of Morinda on Cousin Island, and the associated improved foraging for the warbler, was an important part of the recovery of the species.

Breeding habits

[edit]Seychelles warblers demonstrate cooperative breeding, a reproductive system in which adult male and female helpers assist the parents in providing care and feeding the young.[12] The helpers may also aid in territory defense, predator mobbing, nest building, and incubation (females only).[13] Breeding pairs with helpers have increased reproductive success and produced more offspring that survived per year than breeding pairs with the helpers removed.[14] Helpers only feed the young of their parents or close relatives and do not feed unrelated young. This is evidence for the kin-selected adaptation of providing food for the young. The indirect fitness benefits gained by helping close kin are greater than the direct fitness benefits gained as a breeder. This could be evidence for the kin-selected adaptation of providing food for the young.

On high-quality territories where there is more insect prey available, young birds were more likely to stay as helpers rather than moving to low-quality territories as breeders.[15] On low quality territories, having a helper is unfavorable because of increased resource competition. Females are more likely to become helpers,[16] which may explain the adaptive sex ratio bias seen in the Seychelles warblers. On high quality territories, females produce 90% daughters; on low quality territories, they produce 80% sons. Clutch sex ratio is skewed towards daughters overall.[17] When females are moved to higher quality territories, they produce two eggs in a clutch instead of a single egg, with both eggs skewed towards the production of females. This change suggests that Seychelles warblers may have pre-ovulation control of offspring sex ratio, although the exact mechanism is unknown.

Seychelles warblers are socially monogamous, whereby a male and female form a long-term pair bond and cooperate to raise their young. Occasionally, a male and female may break their pair bond, a phenomenon known as divorce. The percentage of bonded pairs which undergo divorce varies from 1% to 16% per year, with more divorces occurring in years with very low or very high rainfall. However, divorce rates do not appear to be associated with decreased reproductive success. It has been suggested that physiological stress from harsh environmental conditions may be the cause of the increased divorce rates, rather than changes in reproductive success.[18]

References

[edit]- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Acrocephalus sechellensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22714882A94431883. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22714882A94431883.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ a b Penny, M. (1974): The Birds of Seychelles and the Outlying Islands

- ^ Johnson, Thomas F.; Brown, Thomas J.; Richardson, David S.; Dugdale, Hannah L. (2018). "The importance of post-translocation monitoring of habitat use and population growth: Insights from a Seychelles Warbler (Acrocephalus sechellensis) translocation". Journal of Ornithology. 159 (2): 439–446. doi:10.1007/s10336-017-1518-8. S2CID 4519848.

- ^ Leisler, Bernd; Petra Heidrich; Karl Schulze-Hagen; Michael Wink (1997). "Taxonomy and phylogeny of reed warblers (genus Acrocephalus) based on mtDNA sequences and morphology". Journal of Ornithology. 138 (4): 469–496. Bibcode:1997JOrni.138..469L. doi:10.1007/BF01651381. S2CID 40665930.

- ^ Helbig, Andreas; Ingrid Seibold (1999). "Molecular Phylogeny of Palearctic–African Acrocephalus and Hippolais Warblers (Aves: Sylviidae". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 11 (2): 246–260. Bibcode:1999MolPE..11..246H. doi:10.1006/mpev.1998.0571. PMID 10191069.

- ^ Bairlein, Franz; Alström, Per; Aymí, Raül; Clement, Peter; Dyrcz, Andrzej; Gargallo, Gabriel; Hawkins, Frank; Madge, Steve; Pearson, David; Svensson, Lars (2006), "Family Sylviidae (Old World Warblers)", in del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Christie, David (eds.), Handbook of the Birds of the World. Volume 11, Old World Flycatchers to Old World Warblers, Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, p. 635, ISBN 978-84-96553-06-4

- ^ a b Skerrett A, Bullock I & Disley T (2001) Birds of Seychelles. Helm Field Guides ISBN 0-7136-3973-3

- ^ Dowset-Lemaire, Francoise (1994). "The song of the Seychelles Warbler Acrocephalus sechellensis and its African relative". Ibis. 136 (4): 489–491. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1994.tb01127.x.

- ^ Richardson D. (2001) Species Conservation Assessment and Action Plan, Seychelles Warbler. Nature Seychelles.

- ^ "Seychelles Warbler Acrocephalus sechellensis". BirdLife International. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ^ Komdeur J, Pels M (2005). "Rescue of the Seychelles warbler on Cousin Island, Seychelles: The role of habitat restoration". Biological Conservation. 124 (1): 15–26. Bibcode:2005BCons.124...15K. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2004.12.009.

- ^ Komdeur, Jan (1994). "The Effect of Kinship on Helping in the Cooperative Breeding Seychelles Warbler (Acrocephalus sechellensis)" (PDF). Proceedings: Biological Sciences. 256 (1345): 47–52. Bibcode:1994RSPSB.256...47K. doi:10.1098/rspb.1994.0047. JSTOR 49592. S2CID 54796150.

- ^ Komdeur, J. (1994). "The Effect of Kinship on Helping in the Cooperative Breeding Seychelles Warbler" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society. 256 (1345): 47–52. doi:10.1098/rspb.1994.0047. S2CID 54796150.

- ^ Komdeur, J. (1992). "Experimental Evidence for helping and hindering by previous offspring in the cooperative-breeding Seychelles warbler Acrocephalus sechellensis" (PDF). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 34 (3): 175–186. doi:10.1007/BF00167742. S2CID 35183524.

- ^ Komdeur, J. (1992). "Importance of habitat saturation and territory quality for evolution of cooperative breeding in the Seychelles warbler". Letters to Nature. 358 (6386): 493–495. Bibcode:1992Natur.358..493K. doi:10.1038/358493a0. S2CID 4364419.

- ^ Davies, N. B., Krebs J. R., West, S. A. (2012). An Introduction to Behavioural Ecology. Fourth Edition. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

- ^ Komdeur, J.; Magrath, M. J.; Krackow, S (2002). "Pre-ovulation control of hatchling sex ratio in the Seychelles warbler". Proceedings of the Royal Society. 269 (1495): 1067–1072. doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.1965. PMC 1690984. PMID 12028765.

- ^ Bentlage, A. A.; Speelman, F. J. D.; Komdeur, J.; Burke, T.; Richardson, D. S.; Dugdale, H. L. (2024-11-11). "Rainfall is associated with divorce in the socially monogamous Seychelles warbler". Journal of Animal Ecology. doi:10.1111/1365-2656.14216. ISSN 0021-8790.