A Boy Named Charlie Brown

| A Boy Named Charlie Brown | |

|---|---|

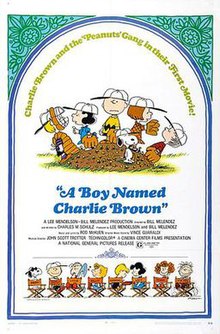

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Bill Melendez |

| Written by | Charles M. Schulz |

| Produced by | Lee Mendelson |

| Starring |

|

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | National General Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 85 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.1 million[3] |

| Box office |

|

A Boy Named Charlie Brown is a 1969 American animated musical comedy-drama film, produced by Cinema Center Films, distributed by National General Pictures, and directed by Bill Melendez with a screenplay by Charles M. Schulz.[5] It is the first feature film based on the Peanuts comic strip.[6] Starring Peter Robbins, Pamelyn Ferdin, Glenn Gilger, and Andy Pforsich, the film follows the titular character as he tries to win the National Spelling Bee, with Snoopy and Linus by his side. The film was also produced by Lee Mendelson. It was also distributed by National General Pictures and produced by Melendez Films.

The film was based on a comic strip storyline from February 1966, which ended differently when Charlie Brown lost his local school's spelling bee. Regular Peanuts composer Vince Guaraldi and John Scott Trotter composed the score while Rod McKuen wrote many of the songs as well as the title song "A Boy Named Charlie Brown". This film was the last time Peter Robbins provided the voice of Charlie Brown.

Releasing on December 4, 1969, A Boy Named Charlie Brown was a box-office success, grossing $12 million and was positively received by critics. The franchise would go on to produce four more Peanuts films.

Plot

[edit]When Charlie Brown's baseball team loses their first league game of the season, he becomes morose that he will never win anything. On the way to school one day, Lucy jokingly suggests to Charlie Brown that he enter the school spelling bee. However, Linus encourages him to participate despite the jeers of Lucy, Violet, and Patty.

Charlie Brown nervously enters the spelling bee and defeats his classmates. As he studies for the school championship, he and Linus sing a song about the spelling mnemonic "I Before E" as Snoopy accompanies them on a Jew's harp. During class, Charlie Brown freezes when challenged with perceive, but recovers when Snoopy plays the song's accompaniment outside the classroom window; Charlie Brown wins. His classmates cheerfully follow him home. However, Lucy, proclaiming herself his agent, then tells Charlie Brown that he must now take part in the National Spelling Bee in New York City, and he is again filled with self-doubt. As Charlie Brown boards the bus for New York, Linus reluctantly offers him his blanket for good luck, and the other kids cheer for him.

Back at home, Linus suffers terrible withdrawal after being separated from his blanket, and convinces Snoopy to go with him to New York to find Charlie Brown and recover it. They find Charlie Brown exhausted from studying for the spelling bee in his hotel room, without any knowledge of the blanket's whereabouts. After an exhaustive search that leads Linus outside the hotel, he returns to find Charlie Brown using the blanket as a shoe-shine cloth. Charlie Brown competes in the spelling bee with Linus and Snoopy in the audience and the rest of the kids watching it on television at home. One-by-one, the other contestants are eliminated until only Charlie Brown and one other boy remain. However, after Charlie Brown spells several words correctly, he is eliminated when he accidentally (and ironically, given that Snoopy is a beagle) misspells beagle as B–E–A–G–E–L, much to the despair of him and his friends. Lucy, who is equally ashamed that Charlie Brown lost, says that he made her mad and turns off the TV.

Despite being the national runner-up, Charlie Brown returns home depressed and defeated. The next day, Linus visits a moody and morose Charlie Brown, who has spent the entire day in bed and refuses to see or talk to anybody. Linus tells him that all the kids missed him and that they won their first game of the season. This worsens Charlie Brown's bad mood, and he says he will never return to school or do anything again. However, Linus points out that the world did not end despite Charlie Brown’s defeat. After Linus leaves, he thinks for a moment, gets dressed, and goes outside. He sees the other kids playing, and when he spots Lucy as she plays with a football, he sneaks up behind her to kick it. She pulls it away, welcomes him home and they look at us as the film ends.

Cast

[edit]- Peter Robbins as Charlie Brown

- Pamelyn Ferdin as Lucy van Pelt

- Glenn Gilger as Linus van Pelt

- Andy Pforsich as Schroeder

- Sally Dryer as Patty

- Bill Melendez as Snoopy

- Anne Altieri as Violet

- Erin Sullivan as Sally Brown

- Lynda Mendelson as Frieda

- Christopher DeFaria as Pig-Pen

- David Carey as 2nd Boy

- Guy Pforsich as 3rd Boy

Shermy appears in this film but does not have a speaking role. Peppermint Patty and 5 also appear in silent roles.

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]The film was partly based on a series of Peanuts comic strips originally published in newspapers in February 1966. That story had a much different ending: Charlie Brown was eliminated in his class spelling bee right away for misspelling the word maze ("M–A–Y–S" while thinking of baseball legend Willie Mays), thus confirming Violet's prediction that he would make a fool of himself. He then screams at his teacher in frustration, causing him to be sent to the principal's office. (A few gags from that storyline, however, were also used in the 1967 TV special You're in Love, Charlie Brown.)

Music

[edit]The film also included several original songs, some of which boasted vocals for the first time: "Failure Face", "I Before E" and "Champion Charlie Brown" (Before the film, musical pieces in Peanuts specials were primarily instrumental, except for a few traditional songs in A Charlie Brown Christmas.) Rod McKuen wrote and sang the title song. He also wrote "Failure Face" and "Champion Charlie Brown".

The instrumental tracks interspersed throughout the film were composed by Vince Guaraldi and arranged by John Scott Trotter (who also wrote "I Before E"). The music consisted mostly of uptempo jazz tunes that had been heard since some of the earliest Peanuts television specials aired back in 1965; however, for the film, they were given a more "theatrical" treatment, with lusher horn-filled arrangements. Instrumental tracks used in it included "Skating" (first heard in A Charlie Brown Christmas) and "Baseball Theme" (first heard in Charlie Brown's All-Stars).[7] When discussing the augmentation of Guaraldi's established jazz scores with additional musicians, Lee Mendelson commented, "It wasn't that we thought Vince's jazz couldn't carry the movie, but we wanted to supplement it with some 'big screen music.' We focused on Vince for the smaller, more intimate Charlie Brown scenes; for the larger moments, we turned to Trotter's richer, full-score sound."[8] Guaraldi's services were passed over entirely for the second Peanuts feature film, Snoopy Come Home, with Mendelson turning to longtime Disney composers, the Sherman Brothers, to compose the music score.

The segment during the "Skating" sequence was choreographed by American figure skater Skippy Baxter. A segment during the middle of the film, in which Schroeder plays the entire 2nd Movement of Beethoven's Sonata Pathétique was performed by Ingolf Dahl. Dahl also performs the excerpts of the 1st and 3rd movements which appear in the film and are also played by Schroeder. Only the 3rd Movement (Rondo: Allegro) can be found on A Boy Named Charlie Brown: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack and only as a shortened bonus track.

The film also features a Jew's harp, which Snoopy plays to help Charlie Brown with his spelling.

Vince Guaraldi's songs were mostly from other specials and included (in addition to "Skating" and "Baseball Theme") "Blue Charlie Brown", "Good Grief", "Snoopy Surfing", and "Linus and Lucy" (several renditions are featured, including 2 slowed down renditions, one in minor key, featured while Linus was looking for his blanket and of course, the traditional rendition when he finally finds it). Guaraldi also plays a rendition of "Champion Charlie Brown" in the opening credits on the piano.

The French-language version replaces Rod McKuen's vocals with a French version sung by Serge Gainsbourg, "Un petit garçon nommé Charlie Brown".

A soundtrack album with dialogue from the film was released on the Columbia Masterworks label in 1970 titled A Boy Named Charlie Brown: Selections from the Film Soundtrack. The first all-music version was released on CD by Kritzerland Records as a limited issue of 1,000 copies in 2017, titled A Boy Named Charlie Brown: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack.[9]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]The film premiered at the Radio City Music Hall in New York City, only the third animated feature to play there after Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) and Bambi (1942).[1][10]

The film was a success at the box office, earning $12 million.[11][12] In its first week at Radio City Music Hall, it grossed $230,000, including a record $60,123 on Saturday, December 6.[13] In its second week, it grossed $290,000 which made it number one in the United States.[14] During Christmas week, it grossed $315,253 at Radio City Music Hall, which Cinema Center Films claimed was the biggest single week gross worldwide (at one theater) in the history of the cinema.[15]

Critical response

[edit]The film was well received by critics and holds a 95% rating at Rotten Tomatoes based on 21 reviews, with an average rating of 7.60/10.[16]

Time praised its use of "subtle, understated colors" and its scrupulous fidelity to the source material, calling it a message film that "should not be missed." The New York Times' Vincent Canby wrote: "A practically perfect screen equivalent to the quiet joys to be found in almost any of Charles M. Schulz's Peanuts comic strips. I do have some reservations about the film, but it's difficult—perhaps impossible—to be anything except benign towards a G-rated, animated movie that manages to include references to St. Stephen, Thomas Eakins, Harpers Ferry, baseball, contemporary morality (as it relates to Charlie Brown's use of his 'bean ball'), conservation and kite flying. "[17]

Legacy

[edit]A 1971 Associated Press story argued the success of the film "broke the Disney monopoly" on animated feature films that had existed since the 1937 release of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. "The success of 'Peanuts' started a trend", animation producer Fred Calvert told the AP, "but I hope the industry is not misled into thinking that animation is the only thing. You need to have a solid story and good characters, too. Audiences are no longer fascinated by the fact that Mickey Mouse can spit."[18]

In 2021, Patrick Galvan of Ourculture stated in his article about the film, "As indicated in Canby’s description, it’d successfully preserved what made the comic special to begin with; it was also a triumph cinematically, packed with stunning visuals and supplemented by an outstanding musical score. But the film had also given me something I hadn’t quite expected. After watching Charlie Brown’s silver screen debut, I was convinced I’d seen one of the great American movies about a subject rarely portrayed so honestly and inspiringly in a motion picture."[19]

Awards and nominations

[edit]The film was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Song Score, but lost to The Beatles' Let It Be.

Home media

[edit]The film was first released on VHS, CED Videodisc, and Betamax in July 1983 through CBS/Fox Video, before seeing another VHS, Betamax, and LaserDisc release in 1984, then several more in 1985, September 26, 1991, February 20, 1992, and 1995 by CBS Home Entertainment through 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment, and May 29, 2001, through Paramount Home Entertainment, before making its Region 1 DVD debut in the original 1.85:1 anamorphic widescreen aspect ratio on March 28, 2006, by Paramount Home Entertainment/CBS Home Entertainment (co-producer Cinema Center Films was owned by CBS). The DVD has more than six minutes of footage not seen since the 1969 test screening and premiere. The footage consists of new scenes completely excised from earlier home video releases (VHS, CED Laserdisc, Japanese DVD) and TV prints — most notably, a scene of Lucy's infamous "pulling-away-the-football" trick after her slide presentation of Charlie Brown's faults (and her instant replay thereof), as well as extending existing scenes. The film was released on Blu-ray on September 6, 2016, along with Snoopy Come Home, however, unlike the DVD releases, both films are presented in an open-matte 4:3 ratio.[20] The film earned $6 million in rentals.[21][22]

See also

[edit]- Peanuts filmography

- Snoopy Come Home

- Race for Your Life, Charlie Brown

- Bon Voyage, Charlie Brown (And Don't Come Back!)

- The Peanuts Movie

References

[edit]- ^ a b A Boy Named Charlie Brown at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- ^ "A Boy Named Charlie Brown (U)". British Board of Film Classification. April 30, 1970. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- ^ Warga, Wayne (March 29, 1970). "Schulz, Charlie Brown Finally Make It to the Movies: Peanuts Makes It to the Movies". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Lynderey, Michael (November 5, 2015). "November 2015 Box Office Forecast". Box Office Prophets. p. 3. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. p. 169. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

- ^ Solomon, Charles (2012). The Art and Making of Peanuts Animation: Celebrating Fifty Years of Television Specials. Chronicle Books. pp. 94–97. ISBN 978-1452110912.

- ^ Bang, Derrick. "Vince Guaraldi on LP and CD: A Boy Named Charlie Brown: Selections from the Film Soundtrack". fivecentsplease.org. Derrick Bang, Scott McGuire. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ Bang, Derrick. Liner notes for A Boy Named Charlie Brown: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack (2017); Kritzerland, Inc. Retrieved 7 May 2020

- ^ A Boy Named Charlie Brown: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack at kritzerland.com

- ^ "'Charlie Brown' Hall's Xmas Pic; 'Max' Precedes?". Variety. September 17, 1969. p. 6.

- ^ "November 2015 Box Office Forecast", 5 November 2015, p. 3.

- ^ Boxofficeprophets.com Archived December 22, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Shopping Slump Vs. Sinewy Few in N.Y.; Cartoon Zingy 230G, Hall; 'Minx' Halls 45G, 3d Week In Two". Variety. December 9, 1969. pp. 18–19.

- ^ "50 Top-Grossing Films". Variety. December 24, 1969. p. 11.

- ^ "A Modest Announcement (advertisement)". Variety. January 14, 1970. pp. 10–11. Retrieved April 7, 2024 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ A Boy Named Charlie Brown at Rotten Tomatoes

- ^ Canby, Vincent (December 5, 1969). "Screen: Good Old Charlie Brown Finds a Home". The New York Times. Retrieved December 2, 2013.

- ^ "Disney Is Losing Cartoon Monopoly". Sarasota Herald-Tribune (AP). September 8, 1971.

- ^ Galvan, Patrick (March 11, 2021). "Looking Back on A Boy Named Charlie Brown". Our Culture. Retrieved May 26, 2024.

- ^ Amazon.com

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1970", Variety, 6 January 1971, p. 11.

- ^ A Boy Named Charlie Brown (1969) – Box office / business

External links

[edit]- 1969 films

- Peanuts films

- 1969 animated films

- 1969 children's films

- 1960s American animated films

- 1960s musical comedy-drama films

- American children's animated comedy films

- American musical comedy-drama films

- Children's comedy-drama films

- Cinema Center Films films

- Comics adapted into animated films

- 1960s English-language films

- Films about spelling competitions

- Films based on American comics

- Films directed by Bill Melendez

- Animated films set in New York City

- Peanuts music

- Films with screenplays by Charles M. Schulz

- 1969 directorial debut films

- 1960s children's animated films

- Animated films about children

- English-language musical comedy-drama films