Sack of Rome (410)

| Sack of Rome (410) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the fall of the Western Roman Empire | |||||||

The Sack of Rome in 410 by the Barbarians by Joseph-Noël Sylvestre, 1890 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Visigoths |

Western Roman Empire Huns[a] | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Alaric I Athaulf | Honorius | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Possibly 40,000 soldiers[6] Unknown number of civilian followers | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

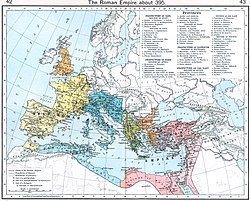

The sack of Rome on 24 August 410 AD was undertaken by the Visigoths led by their king, Alaric. At that time, Rome was no longer the administrative capital of the Western Roman Empire, having been replaced in that position first by Mediolanum (now Milan) in 286 and then by Ravenna in 402. Nevertheless, the city of Rome retained a paramount position as "the eternal city" and a spiritual center of the Empire. This was the first time in almost 800 years that Rome had fallen to a foreign enemy, and the sack was a major shock to contemporaries, friends and foes of the Empire alike.

The sacking of 410 is seen as a major landmark in the fall of the Western Roman Empire. St. Jerome, living in Bethlehem, wrote: "the city which had taken the whole world was itself taken".[7]

Background

[edit]The Germanic tribes had undergone massive technological, social, and economic changes after four centuries of contact with the Roman Empire. From the first to fourth centuries, their populations, economic production, and tribal confederations grew, and their ability to conduct warfare increased to the point of challenging Rome.[8]

The Goths, one of the Germanic tribes, had invaded the Roman Empire on and off since 238.[9] But in the late 4th century, the Huns began to invade the lands of the Germanic tribes, and pushed many of them into the Roman Empire with greater fervor.[10] In 376, the Huns forced many Therving Goths led by Fritigern and Alavivus to seek refuge in the Eastern Roman Empire. Soon after, starvation, high taxes, hatred from the Roman population, and governmental corruption turned the Goths against the empire.[11]

The Goths rebelled and began looting and pillaging throughout the eastern Balkans. A Roman army, led by the Eastern Roman emperor Valens, marched to put them down. At the Battle of Adrianople in 378, Fritigern decisively defeated emperor Valens, who was killed in battle.[11] Peace was eventually established in 382 when the new Eastern emperor, Theodosius I, signed a treaty with the Thervings, who would become known as the Visigoths. The treaty made the Visigoths subjects of the empire as foederati. They were allotted the northern part of the dioceses of Dacia and Thrace, and while the land remained under Roman sovereignty and the Visigoths were expected to provide military service, they were considered autonomous.[12]

Fritigern died around 382.[13] Possibly in 391, a Gothic chieftain named Alaric was declared king by a group of Visigoths, though the exact time this happened (Jordanes says Alaric was made king in 400[14] and Peter Heather says 395[15]) and nature of this position are debated.[16][17] He then led an invasion into Eastern Roman territory outside of the Goths' designated lands. Alaric was defeated by Theodosius and his general Flavius Stilicho in 392, who forced Alaric back into Roman vassalage.[16][18]

In 394, Alaric led a force of Visigoths as part of Theodosius' army to invade the Western Roman Empire. At the Battle of the Frigidus, around half the Visigoths present died fighting the Western Roman army led by the usurper Eugenius and his general Arbogast.[19] Theodosius won the battle, and although Alaric was given the title comes for his bravery, tensions between the Goths and Romans grew as it seemed the Roman generals had sought to weaken the Goths by making them bear the brunt of the fighting. Alaric was also enraged he had not been granted a higher office in the imperial administration.[20]

Visigothic invasion of Rome

[edit]

When Theodosius died on 10 January 395, the Visigoths considered their 382 treaty with Rome to have ended.[21] Alaric quickly led his warriors back to their lands in Moesia, gathered most of the federated Goths in the Danubian provinces under his leadership, and instantly rebelled, invading Thrace and approaching the Eastern Roman capital of Constantinople.[22][23] The Huns, at the same moment, invaded Asia Minor.[22]

The death of Theodosius had also wracked the political structure of the empire: Theodosius' sons, Honorius and Arcadius, were given the Western and Eastern empires, respectively, but they were young and needed guidance. A power struggle emerged between Stilicho, who claimed guardianship over both emperors but was still in the West with the army that had defeated Eugenius, and Rufinus, the praetorian prefect of the East, who took the guardianship of Arcadius in the Eastern capital of Constantinople. Stilicho claimed that Theodosius had awarded him with sole guardianship on the emperor's deathbed and claimed authority over the Eastern Empire as well as the West.[24]

Rufinus negotiated with Alaric to get him to withdraw from Constantinople (perhaps by promising him lands in Thessaly). Whatever the case, Alaric marched away from Constantinople to Greece, looting the diocese of Macedonia.[25][26]

Magister utriusque militiae Stilicho marched east at the head of a combined Western and Eastern Roman army out of Italy. Alaric fortified himself behind a circle of wagons on the plain of Larissa, in Thessaly, where Stilicho besieged him for several months, unwilling to seek battle. Eventually, Arcadius, under the apparent influence of those hostile to Stilicho, commanded him to leave Thessaly.[27]

Stilicho obeyed the orders of his emperor by sending his Eastern troops to Constantinople and leading his Western ones back to Italy.[26][28] The Eastern troops Stilicho had sent to Constantinople were led by a Goth named Gainas. When Rufinus met the soldiers, he was hacked to death in November 395. Whether that was done on the orders of Stilicho, or perhaps on those of Rufinus' replacement Eutropius, is unknown.[29]

The withdrawal of Stilicho freed Alaric to pillage much of Greece, including Piraeus, Corinth, Argos, and Sparta. Athens was able to pay a ransom to avoid being sacked.[26] It was only in 397 that Stilicho returned to Greece, having rebuilt his army with mainly barbarian allies and believing the eastern Roman government would now welcome his arrival.[30] After some fighting, Stilicho trapped and besieged Alaric at Pholoe.[31] Then, once again, Stilicho retreated to Italy, and Alaric marched into Epirus.[32]

Why Stilicho once again failed to dispatch Alaric is a matter of contention. It has been suggested that Stilicho's mostly-barbarian army had been unreliable or that another order from Arcadius and the Eastern government forced his withdrawal.[30] Others suggest that Stilicho made an agreement with Alaric and betrayed the East.[33] Whatever the case, Stilicho was declared a public enemy in the Eastern Empire the same year.[31]

Alaric's rampage in Epirus was enough to make the eastern Roman government offer him terms in 398. They made Alaric magister militum per Illyricum, giving him the Roman command he wanted and giving him free rein to take what resources he needed, including armaments, in his assigned province.[30] Stilicho, in the meantime, put down a rebellion in Africa in 399, which had been instigated by the eastern Roman empire, and married his daughter Maria to the 11-year-old Western emperor, Honorius, strengthening his grip on power in the West.[30]

First Visigothic invasion of Italy

[edit]Aurelianus, the new praetorian prefect of the east after Eutropius' execution, stripped Alaric of his title to Illyricum in 400.[34] Between 700 and 7,000 Gothic soldiers and their families were slaughtered in a riot at Constantinople on 12 July 400.[35][36] Gainas, who at one point had been made magister militum, rebelled, but he was killed by the Huns under Uldin, who sent his head back to Constantinople as a gift.[citation needed]

With these events, particularly Rome's use of the feared Huns, and cut off from Roman officialdom, Alaric felt his position in the East was precarious.[35] So, while Stilicho was busy fighting an invasion of Vandals and Alans in Rhaetia and Noricum, Alaric led his people into an invasion of Italy in 401, reaching it in November without encountering much resistance. The Goths captured a few unnamed cities and besieged the Western Roman capital Mediolanum.[27]

Stilicho, now with Alan and Vandal federates in his army, relieved the siege, forcing a crossing at the Adda river. Alaric retreated to Pollentia.[37] On Easter Sunday, 6 April 402, Stilicho launched a surprise attack which became the Battle of Pollentia. The battle ended in a draw, and Alaric fell back.[38] After brief negotiations and maneuvers, the two forces clashed again at the Battle of Verona, where Alaric was defeated and besieged in a mountain fortress, taking heavy casualties.

At this point, a number of Goths in Alaric's army started deserting him, including Sarus, who went over to the Romans.[39] Alaric and his army then withdrew to the borderlands next to Dalmatia and Pannonia.[40] Honorius, fearful after the near capture of Mediolanum, moved the Western Roman capital to Ravenna, which was more defensible with its natural swamps and more escapable with its access to the sea.[41][42] Moving the capital to Ravenna may have disconnected the Western court from events beyond the Alps towards a preoccupation with the defense of Italy, weakening the Western Empire as a whole.[43]

In time, Alaric became an ally of Stilicho, agreeing to help claim the praetorian prefecture of Illyricum for the Western Empire. To that end, Stilicho named Alaric magister militum of Illyricum in 405. However, the Goth Radagaisus invaded Italy that same year, putting any such plans on hold.[44] Stilicho and the Romans, reinforced by Alans, Goths under Sarus, and Huns under Uldin, managed to defeat Radagaisus in August 406, but only after the devastation of northern Italy.[45][46] 12,000 of Radagaisus' Goths were pressed into Roman military service, and others were enslaved. So many were sold into slavery by the victorious Roman forces that slave prices temporarily collapsed.[47]

Only in 407 did Stilicho turn his attention back to Illyricum, gathering a fleet to support Alaric's proposed invasion. But then the Rhine limes collapsed under the weight of hordes of Vandals, Suebi, and Alans who flooded into Gaul. The Roman population attacked there thus rose in rebellion under the usurper Constantine III.[44] Stilicho reconciled with the Eastern Roman Empire in 408, and the Visigoths under Alaric had lost their value to Stilicho.[48]

Alaric then invaded and took control of parts of Noricum and upper Pannonia in the spring of 408. He demanded 288,000 solidi (four thousand pounds of gold), and threatened to invade Italy if he did not get it.[44] This was equivalent to the amount of money earned in property revenue by a single senatorial family in one year.[49] Only with the greatest difficulty was Stilicho able to get the Roman Senate to agree to pay the ransom, which was to buy the Romans a new alliance with Alaric who was to go to Gaul and fight the usurper Constantine III.[50] The debate on whether to pay Alaric weakened Stilicho's relationship with Honorius.[51]

Before payment could be received, however, the Eastern Roman Emperor Arcadius died of illness on 1 May 408. He was succeeded by his young son, Theodosius II. Honorius wanted to go East to secure his nephew's succession, but Stilicho convinced him to stay and allow Stilicho himself to go instead.[48]

Olympius, a palatine official and an enemy of Stilicho's, spread false rumors that Stilicho planned to place his own son Eucherius on the throne of the East, and many came to believe them. Roman soldiers mutinied and began killing officials who were known supporters of Stilicho.[52] Stilicho's barbarian troops offered to attack the mutineers, but Stilicho forbade it. Stilicho instead went to Ravenna to meet with the Emperor to resolve the crisis.[53]

Honorius, now believing the rumors of Stilicho's treason, ordered his arrest. Stilicho sought sanctuary in a church in Ravenna, but he was lured out with promises of safety. Stepping outside, he was arrested and told he was to be immediately executed on Honorius' orders. Stilicho refused to allow his followers to resist, and he was executed on 22 August 408. Stilicho's execution stopped the payment to Alaric and his Visigoths, who had received none of it.[50]

The half-Vandal, half-Roman general is credited with keeping the Western Roman Empire from crumbling during his 13 years of rule, and his death would have profound repercussions for the West.[52] His son Eucherius was executed shortly after in Rome.[54]

Olympius was appointed magister officiorum and replaced Stilicho as the power behind the throne. His new government was strongly anti-Germanic and obsessed with purging any and all of Stilicho's former supporters. Roman soldiers began to indiscriminately slaughter allied barbarian foederati soldiers and their families in Roman cities.[55] Thousands of them fled Italy and sought refuge with Alaric in Noricum.[56] Zosimus reports the number of refugees as 30,000, but Peter Heather and Thomas Burns believe that number is impossibly high.[56] Heather argues that Zosimus had misread his source and that 30,000 is the total number of fighting-men under Alaric's command after the refugees joined Alaric.[57]

Second Visigothic invasion of Italy

[edit]First siege of Rome

[edit]Attempting to come to an agreement with Honorius, Alaric asked for hostages, gold, and permission to move to Pannonia, but Honorius refused.[56] Alaric, aware of the weakened state of defenses in Italy, invaded in early October, six weeks after Stilicho's death. He also sent word of this news to his brother-in-law Ataulf asking him to join the invasion as soon as he was able with reinforcements.[58]

Alaric and his Visigoths sacked Ariminum and other cities as they moved south.[59] Alaric's march was unopposed and leisurely, as if they were going to a festival, according to Zosimus.[58] Sarus and his band of Goths, still in Italy, remained neutral and aloof.[55]

The city of Rome may have held as many as 800,000 people, making it the largest in the world at the time.[60] The Goths under Alaric laid siege to the city in late 408. Panic swept through its streets, and there was an attempt to reinstate pagan rituals in the still religiously mixed city to ward off the Visigoths.[61] Pope Innocent I even agreed to it, provided it be done in private. The pagan priests, however, said the sacrifices could only be done publicly in the Roman Forum, and the idea was abandoned.[62]

Serena, the wife of the proscribed Stilicho and a cousin of emperor Honorius, was in the city and believed by the Roman populace, with little evidence, to be encouraging Alaric's invasion. Galla Placidia, the sister of the emperor Honorius, was also trapped in the city and gave her consent to the Roman Senate to execute Serena, who was then strangled to death.[63]

Hopes of help from the Imperial government faded as the siege continued and Alaric took control of the Tiber River, which cut the supplies going into Rome. Grain was rationed to one-half and then one-third of its previous amount. Starvation and disease rapidly spread throughout the city, and rotting bodies were left unburied in the streets.[64]

The Roman Senate then decided to send two envoys to Alaric. When the envoys boasted to him that the Roman people were trained to fight and ready for war, Alaric laughed at them and said, "The thickest grass is easier to cut than the thinnest."[64] The envoys asked under what terms the siege could be lifted, and Alaric demanded all the gold and silver, household goods, and barbarian slaves in the city. One envoy asked what would be left to the citizens of Rome. Alaric replied, "Their lives."[64]

Ultimately, the city was forced to give the Goths 5,000 pounds of gold, 30,000 pounds of silver, 4,000 silken tunics, 3,000 hides dyed scarlet, and 3,000 pounds of pepper in exchange for lifting the siege.[65] The barbarian slaves fled to Alaric as well, swelling his ranks to about 40,000.[66] Many of the barbarian slaves were probably Radagaisus' former followers.[6]

To raise the needed money, Roman senators were to contribute according to their means. This led to corruption and abuse, and the sum came up short. The Romans then stripped down and melted pagan statues and shrines to make up the difference.[67] Zosimus reports one such statue was of Virtus, and that when it was melted down to pay off barbarians it seemed "all that remained of the Roman valor and intrepidity was totally extinguished".[68]

Honorius consented to the payment of the ransom, and with it the Visigoths lifted the siege and withdrew to Etruria in December 408.[55]

Second siege

[edit]

In January 409,[69] the Senate sent an embassy to the imperial court at Ravenna to encourage the Emperor to come to terms with the Goths, and to give Roman aristocratic children as hostages to the Goths as insurance. Alaric would then resume his alliance with the Roman Empire.[55][70] Honorius, under the influence of Olympius, refused and called in five legions from Dalmatia, totaling six thousand men. They were to go to Rome and garrison the city, but their commander, a man named Valens, marched his men into Etruria, believing it cowardly to go around the Goths. He and his men were intercepted and attacked by Alaric's full force, and almost all were killed or captured. Only 100 managed to escape and reach Rome.[69][71]

A second Senatorial embassy, this time including Pope Innocent I, was sent with Gothic guards to Honorius to plead with him to accept the Visigoths' demands.[72] The imperial government also received word that Ataulf, Alaric's brother-in-law, had crossed the Julian Alps with his Goths into Italy with the intent of joining Alaric.[73]

Honorius summoned together all available Roman forces in northern Italy. He placed 300 Huns of the imperial guard under the command of Olympius, and possibly the other forces as well, and ordered him to intercept Ataulf. They clashed near Pisa, and despite his force supposedly killing 1,100 Goths and losing only 17 of his own men, Olympius was forced to retreat back to Ravenna.[72][74] Zosimus seems to imply that only the Huns under Olympius took part in this fight.[2] Ataulf then joined Alaric.

This failure caused Olympius to fall from power and to flee for his life to Dalmatia.[75] Jovius, the praetorian prefect of Italy, replaced Olympius as the power behind the throne and received the title of patrician. Jovius engineered a mutiny of soldiers in Ravenna who demanded the killing of magister utriusque militiae Turpilio and magister equitum Vigilantius; he had both men killed.[75][76][77]

Jovius was a friend of Alaric's and had been a supporter of Stilicho, and thus the new government was open to negotiations.[75] Alaric went to Ariminum to meet Jovius and present his demands. Alaric wanted yearly tribute in gold and grain, and lands in the provinces of Dalmatia, Noricum, and Venetia for his people.[75] Jovius also wrote privately to Honorius, suggesting that if Alaric was offered the position of magister utriusque militiae, they could lessen Alaric's other demands. Honorius rejected the demand for a Roman office, and he sent an insulting letter to Alaric, which was read out in the negotiations.[78][79]

Infuriated, Alaric broke off negotiations, and Jovius returned to Ravenna to strengthen his relationship with the Emperor. Honorius was now firmly committed to war, and Jovius swore on the Emperor's head never to make peace with Alaric.[80]

Alaric himself soon changed his mind when he heard Honorius was attempting to recruit 10,000 Huns to fight the Goths.[75][81] He gathered a group of Roman bishops and sent them to Honorius with his new terms. He no longer sought Roman office or tribute in gold. He now only requested lands in Noricum and as much grain as the Emperor found necessary.[75] Historian Olympiodorus the Younger, writing many years later, considered these terms extremely moderate and reasonable.[79] But it was too late: Honorius' government, bound by oath and intent on war, rejected the offer. Alaric then marched on Rome.[75] The 10,000 Huns never materialized.[82]

Alaric took Portus and renewed the siege of Rome in late 409. Faced with the return of starvation and disease, the Senate met with Alaric.[83] He demanded that they appoint one of their own as Emperor to rival Honorius, and he instigated the election of the elderly Priscus Attalus to that end, a pagan who permitted himself to be baptized. Alaric was then made magister utriusque militiae and his brother-in-law Ataulf was given the position comes domesticorum equitum in the new, rival government, and the siege was lifted.[75]

Heraclian, governor of the food-rich province of Africa, remained loyal to Honorius. Attalus sent a Roman force to subdue him, refusing to send Gothic soldiers there as he was distrustful of their intentions.[84] Attalus and Alaric then marched to Ravenna, forcing some cities in northern Italy to submit to Attalus.[79]

Honorius, extremely fearful at this turn of events, sent Jovius and others to Attalus, pleading that they share the Western Empire. Attalus said he would only negotiate on Honorius' place of exile. Jovius, for his part, switched sides to Attalus and was named patrician by his new master. Jovius wanted to have Honorius mutilated as well (something that was to become common in the Eastern Empire), but Attalus rejected it.[84]

Increasingly isolated and now in pure panic, Honorius was preparing to flee to Constantinople when 4,000 Eastern Roman soldiers appeared at Ravenna's docks to defend the city.[85] Their arrival strengthened Honorius' resolve to await news of what had happened in Africa.

Heraclian had defeated Attalus' force and cut supplies to Rome, threatening another famine in the city.[85] Alaric wanted to send Gothic soldiers to invade Africa and secure the province, but Attalus again refused, distrustful of the Visigoths' intentions for the province.[84] Counseled by Jovius to do away with his puppet emperor, Alaric summoned Attalus to Ariminum and ceremonially stripped him of his imperial regalia and title in the summer of 410. Alaric then reopened negotiations with Honorius.[85]

Third siege and sack

[edit]

Honorius arranged for a meeting with Alaric about 12 kilometres outside of Ravenna. As Alaric waited at the meeting place, Sarus, who was a sworn enemy of Ataulf and now allied to Honorius, attacked Alaric and his men with a small Roman force.[85][86] Peter Heather speculates Sarus had also lost the election for the kingship of the Goths to Alaric in the 390s.[86]

Alaric survived the attack and, outraged at this treachery and frustrated by all the past failures at accommodation, gave up on negotiating with Honorius and headed back to Rome, which he besieged for the third and final time.[87] On 24 August 410 the Visigoths entered Rome through its Salarian Gate, according to some opened by treachery, according to others by want of food, and pillaged the city for three days.[88][89]

Many of the city's great buildings were ransacked, including the mausoleums of Augustus and Hadrian, in which many emperors of the past were buried; the ashes of the urns in both tombs were scattered.[90] Any and all moveable goods were stolen all over the city. Some of the few places the Goths spared were the two major basilicas connected to Peter and Paul, though from the Lateran Palace they stole a massive, 2,025-pound silver ciborium that had been a gift from Constantine.[87] Structural damage to buildings was largely limited to the areas near the old Senate house and the Salarian Gate, where the Gardens of Sallust were burned and never rebuilt.[91][92] The Basilica Aemilia and the Basilica Julia were also burned.[93][94]

The people of Rome were devastated. Many Romans were taken captive, including the Emperor's sister, Galla Placidia. Some citizens would be ransomed, others would be sold into slavery, and still others would be raped and killed.[95] Pelagius, a Roman monk from Britain, survived the siege and wrote an account of the experience in a letter to a young woman named Demetrias.

This dismal calamity is but just over, and you yourself are a witness to how Rome that commanded the world was astonished at the alarm of the Gothic trumpet, when that barbarous and victorious nation stormed her walls, and made her way through the breach. Where were then the privileges of birth, and the distinctions of quality? Were not all ranks and degrees leveled at that time and promiscuously huddled together? Every house was then a scene of misery, and equally filled with grief and confusion. The slave and the man of quality were in the same circumstances, and everywhere the terror of death and slaughter was the same, unless we may say the fright made the greatest impression on those who had the greatest interest in living.[96]

Many Romans were tortured into revealing the locations of their valuables. One was the 85-year-old[97] Saint Marcella, who had no hidden gold as she lived in pious poverty. She was a close friend of St. Jerome, and he detailed the incident in a letter to a woman named Principia who had been with Marcella during the sack.

When the soldiers entered [Marcella's house] she is said to have received them without any look of alarm; and when they asked her for gold she pointed to her coarse dress to show them that she had no buried treasure. However they would not believe in her self-chosen poverty, but scourged her and beat her with cudgels. She is said to have felt no pain but to have thrown herself at their feet and to have pleaded with tears for you [Principia], that you might not be taken from her, or owing to your youth have to endure what she as an old woman had no occasion to fear. Christ softened their hard hearts and even among bloodstained swords natural affection asserted its rights. The barbarians conveyed both you and her to the basilica of the apostle Paul, that you might find there either a place of safety or, if not that, at least a tomb.[98]

Marcella died of her injuries a few days later.[99]

The sack was nonetheless, by the standards of the age (and any age), restrained. There was no general slaughter or wholesale enslavement of the city's inhabitants and the two main basilicas of Peter and Paul were nominated places of sanctuary. Most of the buildings and monuments in the city survived intact, though stripped of their valuables.[87][90]

Refugees from Rome flooded the province of Africa, as well as Egypt and the East.[100][101] Some refugees were robbed as they sought asylum,[101] and St. Jerome wrote that Heraclian, the Count of Africa, sold some of the young refugees into Eastern brothels.[102]

Who would believe that Rome, built up by the conquest of the whole world, had collapsed, that the mother of nations had become also their tomb; that the shores of the whole East, of Egypt, of Africa, which once belonged to the imperial city, were filled with the hosts of her men-servants and maid-servants, that we should every day be receiving in this holy Bethlehem men and women who once were noble and abounding in every kind of wealth but are now reduced to poverty? We cannot relieve these sufferers: all we can do is to sympathize with them, and unite our tears with theirs. [...] There is not a single hour, nor a single moment, in which we are not relieving crowds of brethren, and the quiet of the monastery has been changed into the bustle of a guest house. And so much is this the case that we must either close our doors, or abandon the study of the Scriptures on which we depend for keeping the doors open. [...] Who could boast when the flight of the people of the West, and the holy places, crowded as they are with penniless fugitives, naked and wounded, plainly reveal the ravages of the Barbarians? We cannot see what has occurred, without tears and moans. Who would have believed that mighty Rome, with its careless security of wealth, would be reduced to such extremities as to need shelter, food, and clothing? And yet, some are so hard-hearted and cruel that, instead of showing compassion, they break up the rags and bundles of the captives, and expect to find gold about those who are nothing more than prisoners.[101]

The historian Procopius records a story where, on hearing the news that Rome had "perished", Honorius was initially shocked, thinking the news was in reference to a favorite chicken he had named "Rome" (Latin, Roma):

At that time they say that the Emperor Honorius in Ravenna received the message from one of the eunuchs, evidently a keeper of the poultry, that Rome had perished. And he cried out and said, 'And yet it has just eaten from my hands!' For he had a very large cock, Rome by name; and the eunuch comprehending his words said that it was the city of Rome which had perished at the hands of Alaric, and the emperor with a sigh of relief answered quickly: 'But I thought that my fowl Rome had perished.' So great, they say, was the folly with which this emperor was possessed.[103]

Aftermath

[edit]

After three days of looting and pillage, Alaric quickly left Rome and headed for southern Italy. He took with him the wealth of the city and a valuable hostage, Galla Placidia, the sister of emperor Honorius. The Visigoths ravaged Campania, Lucania, and Calabria. Nola and perhaps Capua were sacked, and the Visigoths threatened to invade Sicily and Africa.[104] However, they were unable to cross the Strait of Messina as the ships they had gathered were wrecked by a storm.[85][105] Alaric died of illness at Consentia in late 410, mere months after the sack.[85] According to legend, he was buried with his treasure by slaves in the bed of the Busento river. The slaves were then killed to hide its location.[106] The Visigoths elected Ataulf, Alaric's brother-in-law, as their new king. The Visigoths then moved north, heading for Gaul. Ataulf married Galla Placidia in 414, but he died one year later. The Visigoths established the Visigothic Kingdom in southwestern Gaul in 418, and they would go on to help the Western Roman Empire fight Attila the Hun at the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields in 451.[107]

The Visigothic invasion of Italy caused land taxes to drop anywhere from one-fifth to one-ninth of their pre-invasion value in the affected provinces.[108] Aristocratic munificence, the local support of public buildings and monuments by the upper classes, ended in south-central Italy after the sack and pillaging of those regions.[109] Using the number of people on the food dole as a guide, Bertrand Lançon estimates the city of Rome's total population fell from 800,000 in 408 to 500,000 by 419.[110]

This was the first time the city of Rome had been sacked in almost 800 years, and it had revealed the Western Roman Empire's increasing vulnerability and military weakness. It was shocking to people across both halves of the Empire who viewed Rome as the eternal city and the symbolic heart of their empire. The Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius II declared three days of mourning in Constantinople.[111] St. Jerome wrote in grief, "If Rome can perish, what can be safe?"[112] In Bethlehem, he detailed his shock in the preface to his commentary on Ezekiel.

[...] intelligence was suddenly brought me of the death of Pammachius and Marcella, the siege of Rome, and the falling asleep of many of my brethren and sisters. I was so stupefied and dismayed that day and night I could think of nothing but the welfare of the community; it seemed as though I was sharing the captivity of the saints, and I could not open my lips until I knew something more definite; and all the while, full of anxiety, I was wavering between hope and despair, and was torturing myself with the misfortunes of other people. But when the bright light of all the world was put out, or, rather, when the Roman Empire was decapitated, and, to speak more correctly, the whole world perished in one city, 'I became dumb and humbled myself, and kept silence from good words, but my grief broke out afresh, my heart glowed within me, and while I meditated the fire was kindled.'[101]

The Roman Empire at this time was still in the midst of religious conflict between pagans and Christians. The sack was used by both sides to bolster their competing claims of divine legitimacy.[113] Paulus Orosius, a Christian priest and theologian, believed the sack was God's wrath against a proud and blasphemous city, and that it was only through God's benevolence that the sack had not been too severe. Rome had lost its wealth, but Roman sovereignty endured, and that to talk to the survivors in Rome one would think "nothing had happened."[114] Other Romans felt the sack was divine punishment for turning away from the traditional pagan gods to Christ. Zosimus, a Roman pagan historian, believed that Christianity, through its abandonment of the ancient traditional rites, had weakened the Empire's political virtues, and that the poor decisions of the Imperial government that led to the sack were due to the lack of the gods' care.[115]

The religious and political attacks on Christianity spurred Saint Augustine to write a defense, The City of God, which went on to become foundational to Christian thought.[116]

The sack was a culmination of many terminal problems facing the Western Roman Empire. Domestic rebellions and usurpations weakened the Empire in the face of external invasions. These factors would permanently harm the stability of the Roman Empire in the west.[117] The Roman army meanwhile became increasingly barbarian and disloyal to the Empire.[118] A more severe sack of Rome by the Vandals followed in 455, and the Western Roman Empire finally collapsed in 476 when the Germanic Odovacer removed the last Western Roman Emperor, Romulus Augustulus, and declared himself King of Italy.

See also

[edit]- Fall of the Western Roman Empire

- Gothic War (376–382)

- List of incidents of cannibalism

- Visigothic Kingdom

References

[edit]- ^ Maenchen-Helfen, Otto J. (2022). Knight, Max (ed.). The World of the Huns Studies in Their History and Culture. University of California Press. p. 60. ISBN 9780520302617. Retrieved 19 November 2022.

- ^ a b Burns, Thomas S. (1994). Barbarians Within the Gates of Rome A Study of Roman Military Policy and the Barbarians, Ca.375–425 A.D. Indiana University Press. p. 236. ISBN 9780253312884. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 13, (Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 126

- ^ Arnold Hugh Martin Jones, The Later Roman Empire, 284–602, (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1964), p. 186.

- ^ Arnold Hugh Martin Jones, The Later Roman Empire, 284–602, (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1964), p. 199.

- ^ a b Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians (Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 224.

- ^ St Jerome, Letter CXXVII. To Principia, s:Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers: Series II/Volume VI/The Letters of St. Jerome/Letter 127 paragraph 12.

- ^ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. 84–100.

- ^ The Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 1, (Cambridge University Press, 1911), p. 203.

- ^ Gordon M. Patterson, Medieval History: 500 to 1450 AD Essentials, (Research & Education Association, 2001), p. 41.

- ^ a b The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 13, (Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp. 95–101.

- ^ Herwig Wolfram, History of the Goths, Trans. Thomas J. Dunlap, (University of California Press, 1988), p. 133.

- ^ Thomas S. Burns, Barbarians Within the Gates of Rome: A Study of Roman Military Policy and the Barbarians, (Indiana University Press, 1994), p. 77.

- ^ Thomas S. Burns, Barbarians Within the Gates of Rome: A Study of Roman Military Policy and the Barbarians, (Indiana University Press, 1994), p. 176.

- ^ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians (Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 462.

- ^ a b Herwig Wolfram, The Roman Empire and Its Germanic Peoples, (University of California Press, 1997), 91.

- ^ Herwig Wolfram, History of the Goths, Trans. Thomas J. Dunlap, (University of California Press, 1988), pp. 143–146.

- ^ Herwig Wolfram, History of the Goths, Trans. Thomas J. Dunlap, (University of California Press, 1988), p. 136.

- ^ Herwig Wolfram, The Roman Empire and Its Germanic Peoples, (University of California Press, 1997), 91–92.

- ^ Herwig Wolfram, The Roman Empire and Its Germanic Peoples, (University of California Press, 1997), 92.

- ^ Herwig Wolfram, History of the Goths, Trans. Thomas J. Dunlap, (University of California Press, 1988), p. 139.

- ^ a b Herwig Wolfram, The Roman Empire and Its Germanic Peoples,(University of California Press, 1997), 92–93.

- ^ Herwig Wolfram, History of the Goths, Trans. Thomas J. Dunlap, (University of California Press, 1988), p. 140.

- ^ Warren T. Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State and Society, (Stanford University Press, 1997), pp. 77–78.

- ^ Warren T. Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State and Society, (Stanford University Press, 1997), p. 79.

- ^ a b c Herwig Wolfram, History of the Goths, Trans. Thomas J. Dunlap, (University of California Press, 1988), p. 141.

- ^ a b Hughes, Ian (2010). Stilicho: The Vandal Who Saved Rome. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. pp. 81–85.

- ^ The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 13, (Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp. 113–114, 430.

- ^ The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 13, (Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 114.

- ^ a b c d The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 13, (Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 115.

- ^ a b Herwig Wolfram, History of the Goths, Trans. Thomas J. Dunlap, (University of California Press, 1988), p. 142.

- ^ Kulikowski, Michael (2019). The Tragedy of Empire: From Constantine to the Destruction of Roman Italy. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-67466-013-7.

- ^ Herwig Wolfram, The Roman Empire and Its Germanic Peoples, (University of California Press, 1997), p. 94.

- ^ Thomas S. Burns, Barbarians Within the Gates of Rome: A Study of Roman Military Policy and the Barbarians, (Indiana University Press, 1994), p. 178.

- ^ a b Herwig Wolfram, History of the Goths, Trans. Thomas J. Dunlap, (University of California Press, 1988), pp. 149–150.

- ^ John Bagnell Bury, History of the Later Roman Empire volume 1, (Dover edition, St Martins Press, 1958), p. 134.

- ^ Herwig Wolfram, History of the Goths, Trans. Thomas J. Dunlap, (University of California Press, 1988), p. 151.

- ^ Herwig Wolfram, History of the Goths, Trans. Thomas J. Dunlap, (University of California Press, 1988), p. 152.

- ^ Herwig Wolfram, History of the Goths, Trans. Thomas J. Dunlap, (University of California Press, 1988), pp. 152–153.

- ^ The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 13, (Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 431.

- ^ Adolph Ludvig Køppen, "The World in the Middle Ages, an Historical Geography", (D. Appleton and Company, 1854), p. 14.

- ^ Herwig Wolfram, The Roman Empire and Its Germanic Peoples, (University of California Press, 1997), 96.

- ^ The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 13, (Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 120.

- ^ a b c Herwig Wolfram, History of the Goths, Trans. Thomas J. Dunlap, (University of California Press, 1988), p. 153.

- ^ The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 13, (Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 121.

- ^ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 194.

- ^ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 198.

- ^ a b Burns, Thomas (1994). Barbarians within the Gates of Rome: A Study of Roman Military Policy and the Barbarians, CA. 375–425 A.D. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-25331-288-4.

- ^ Bertrand Lançon, Rome in Late Antiquity, Trans. Antonia Nevill, (Rutledge, 2001), pp. 36–37.

- ^ a b Herwig Wolfram, History of the Goths, Trans. Thomas J. Dunlap, (University of California Press, 1988), p. 154.

- ^ The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 13, (Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 123.

- ^ a b The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 13, (Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp. 123–124.

- ^ Meaghan McEvoy (2 May 2013). Child Emperor Rule in the Late Roman West, AD 367–455. Oxford University Press. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-19-966481-8.

- ^ John Bagnell Bury, History of the Later Roman Empire volume 1, (Dover edition, St Martins Press, 1958), p. 172.

- ^ a b c d The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 13, (Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 125.

- ^ a b c Thomas S. Burns, Barbarians Within the Gates of Rome: A Study of Roman Military Policy and the Barbarians, (Indiana University Press, 1994), p. 275.

- ^ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 514.

- ^ a b Thomas S. Burns, Barbarians Within the Gates of Rome: A Study of Roman Military Policy and the Barbarians, (Indiana University Press, 1994), p. 277.

- ^ Sam Moorhead and David Stuttard, AD410: The Year that Shook Rome, (The British Museum Press, 2010), pp. 94–95.

- ^ Sam Moorhead and David Stuttard, AD410: The Year that Shook Rome, (The British Museum Press, 2010), p. 23.

- ^ Sam Moorhead and David Stuttard, AD410: The Year that Shook Rome, (The British Museum Press, 2010), pp. 97–98.

- ^ Thomas S. Burns, Barbarians Within the Gates of Rome: A Study of Roman Military Policy and the Barbarians, (Indiana University Press, 1994), p. 235.

- ^ John Bagnell Bury, History of the Later Roman Empire volume 1, (Dover edition, St Martins Press, 1958), p. 175.

- ^ a b c Zosimus. "New History," 5.40.

- ^ J. Norwich, Byzantium: The Early Centuries, 134

- ^ Sam Moorhead and David Stuttard, AD410: The Year that Shook Rome, (The British Museum Press, 2010), p. 101.

- ^ Thomas S. Burns, Barbarians Within the Gates of Rome: A Study of Roman Military Policy and the Barbarians, (Indiana University Press, 1994), p. 234.

- ^ Zosimus. "New History," 5.41.

- ^ a b John Bagnell Bury, History of the Later Roman Empire volume 1, (Dover edition, St Martins Press, 1958), pp. 177–178.

- ^ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians (Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. 224–225

- ^ Zosimus. "New History," 5.42.

- ^ a b Thomas S. Burns, Barbarians Within the Gates of Rome: A Study of Roman Military Policy and the Barbarians, (Indiana University Press, 1994), p. 236.

- ^ Burns, Thomas (1994). Barbarians within the Gates of Rome: A Study of Roman Military Policy and the Barbarians, CA. 375–425 A.D. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-25331-288-4.

- ^ John Bagnell Bury, History of the Later Roman Empire volume 1, (Dover edition, St Martins Press, 1958), p. 178.

- ^ a b c d e f g h The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 13, (Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 126.

- ^ Thomas S. Burns, Barbarians Within the Gates of Rome: A Study of Roman Military Policy and the Barbarians, (Indiana University Press, 1994), pp. 236–238.

- ^ Arnold Hugh Martin Jones, The Later Roman Empire, 284–602, (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1964), p. 175.

- ^ John Bagnell Bury, History of the Later Roman Empire volume 1, (Dover edition, St Martins Press, 1958), p. 179.

- ^ a b c Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 226.

- ^ Gibbon, Edward (2 May 2013). The history of the decline and fall of the Roman Empire. Eighteenth Century Collections Online Text Creation Partnership. p. 302. ISBN 978-0-19-966481-8.

- ^ Arnold Hugh Martin Jones, The Later Roman Empire, 284–602, (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1964), p. 186.

- ^ Arnold Hugh Martin Jones, The Later Roman Empire, 284–602, (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1964), p. 199.

- ^ Thomas S. Burns, Barbarians Within the Gates of Rome: A Study of Roman Military Policy and the Barbarians, (Indiana University Press, 1994), pp. 240–241.

- ^ a b c The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 13, (Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp. 126–127.

- ^ a b c d e f The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 13, (Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 127.

- ^ a b Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 227.

- ^ a b c Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. 227–228.

- ^ Thomas S. Burns, Barbarians Within the Gates of Rome: A Study of Roman Military Policy and the Barbarians, (Indiana University Press, 1994), p. 244.

- ^ Sam Moorhead and David Stuttard, AD410: The Year that Shook Rome, (The British Museum Press, 2010), pp. 124–126.

- ^ a b Sam Moorhead and David Stuttard, AD410: The Year that Shook Rome, (The British Museum Press, 2010), p. 126.

- ^ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. 227–228.

- ^ Jeremiah Donovan, "Rome, Ancient and Modern: And Its Environs" Volume 4, (Crispino Puccinelli, 1842), p. 462.

- ^ David Watkin, The Roman Forum, (Profile Books, 2009), p. 82.

- ^ Arthur Lincoln Frothingham, The Monuments of Christian Rome from Constantine to the Renaissance, (The Macmillan Company, 1908), pp. 58–59.

- ^ Sam Moorhead and David Stuttard, AD410: The Year that Shook Rome, (The British Museum Press, 2010), pp. 131–133.

- ^ William Jones, Ecclesiastical history, in a course of lectures, Vol. 1, (G. Wightman, Paternoster Row and G. J. McCombie, Barbican, 1838), p. 421.

- ^ Sam Moorhead and David Stuttard, AD410: The Year that Shook Rome, (The British Museum Press, 2010), p. 12.

- ^ St Jerome, Letter CXXVII. To Principia, s:Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers: Series II/Volume VI/The Letters of St. Jerome/Letter 127 paragraph 13.

- ^ St Jerome, Letter CXXVII. To Principia, s:Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers: Series II/Volume VI/The Letters of St. Jerome/Letter 127 paragraph 14.

- ^ R. H. C. Davis, A History of Medieval Europe: From Constantine to Saint Louis, (3rd ed. Rutledge, 2006), p. 45.

- ^ a b c d Henry Wace and Philip Schaff, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, (Charles Scribner's Sons, 1912), pp. 499–500.

- ^ Bertrand Lançon, Rome in Late Antiquity, Trans. Antonia Nevill, (Rutledge, 2001), p. 39.

- ^ Procopius, The Vandalic War (III.2.25–26)

- ^ Sam Moorhead and David Stuttard, AD410: The Year that Shook Rome, (The British Museum Press, 2010), p. 134.

- ^ Herwig Wolfram, The Roman Empire and Its Germanic Peoples, (University of California Press, 1997), pp. 99–100.

- ^ Stephen Dando-Collins, The Legions of Rome, (Random House Publisher Services, 2010), p. 576.

- ^ Michael Frassetto, The Early Medieval World, (ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2013), pp. 547–548.

- ^ The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 14, (Cambridge University Press, 2000), p. 14.

- ^ The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 13, (Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 380.

- ^ Bertrand Lançon, Rome in Late Antiquity, Trans. Antonia Nevill, (Rutledge, 2001), pp. 14, 119.

- ^ Eric H. Cline and Mark W. Graham, Ancient Empires: From Mesopotamia to the Rise of Islam (Cambridge University Press, 2011), p. 303.

- ^ Peter Brown, Augustine of Hippo: A Biography (Rev. ed. University of California Press, 2000), p. 288.

- ^ Thomas S. Burns, Barbarians Within the Gates of Rome: A Study of Roman Military Policy and the Barbarians, (Indiana University Press, 1994), p. 233.

- ^ Paulus Orosius, Seven Books of History Against the Pagans 2.3, 7.39–40.

- ^ Stephen Mitchell, A History of the Later Roman Empire, AD 284–641 (Blackwell Publishing, 2007), p. 27.

- ^ Michael Hoelzl and Graham Ward, Religion and Political Thought (The Continuum International Publishing Group, 2006), p. 25.

- ^ Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, (Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 229.

- ^ The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 13, (Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp. 111–112.

Notes

[edit]- ^ The Huns took part in the defense of the Western Roman Empire during the first Visigothic invasion of Italy; after defeating and killing the magister militum Gainas on his own, Uldin, the Hun king, was called to Italy by the Romans, and in August 406 helped to defeat and kill Radagaisus, the Gothic king who had invaded Italy.[1] The Huns also took part in the defense of Rome in the clashes before the second siege (409) of the second Visigothic invasion of Italy, when 300 of them were successful against the Goths, reportedly killing 1,100 of them with just 17 losses before the rest of the Gothic army could rally and drive them back to Ravenna.[2] The Huns were also to participate in greater number, as Honorius attempted to recruit 10,000 of them.[3][4] The news of Honorius' intent caused Alaric to send for him to negotiate new terms. Eventually, however, the 10,000 Huns never materialized.[5]

Further reading

[edit]- The Histories of Olympiodorus of Thebes

- New History of Zosimus

- Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric, Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Kovács, Tamás (2020). "410: Honorius, his rooster, and the eunuch (Procop. Vand. 1.2.25–26)" (PDF). Graeco-Latina Brunensia (2): 131–148. doi:10.5817/GLB2020-2-10.