1938 American Karakoram expedition to K2

The 1938 American Karakoram expedition to K2, more properly called the "First American Karakoram expedition", investigated several routes for reaching the summit of K2, an unclimbed mountain at 28,251 feet (8,611 m) the second highest mountain in the world. Charlie Houston was the leader of what was a small and happily united climbing party. After deciding the Abruzzi Ridge was most favorable, they made good progress up to the head of the ridge at 24,700 feet (7,500 m) on July 19, 1938. However, by then their supply lines were very extended, they were short of food and the monsoon seemed imminent. It was decided that Houston and Paul Petzoldt would make the last push to get as close to the summit as they could and then rejoin the rest of the party in descent. On July 21 the pair reached about 26,000 feet (7,900 m). In favorable weather, they were able to identify a suitable site for a higher camp and a clear route to the summit.[1]

The expedition was regarded as a success and no one had suffered a serious injury. A suitable route up the Abruzzi Ridge had been explored in detail, good sites for tents had been found (sites that would go on to be used in many future expeditions), and they had identified the technically most difficult part of the climb, up House's Chimney at 22,000 feet (6,700 m) (named after Bill House, who had led the two-hour climb up the rock face). The book the team jointly wrote, Five Miles High (Bates & Burdsall 1939), was also successful. The following year, the 1939 American Karakoram expedition took advantage of the reconnaissance to get very near the summit, but their descent led to tragedy.

Background

[edit]K2

[edit]

K2 is on the border between what in 1938 was the British Raj of India (now Pakistan) and the Republic of China. At 28,251 feet (8,611 m) it is the highest point of the Karakoram range and the second highest mountain in the world. The mountain had been spotted in 1856 by the Great Trigonometrical Survey to Kashmir[note 2] and by 1861 Henry Godwin-Austen had reached the Baltoro Glacier and was able to get a clear view of K2 from the slopes of Masherbrum.[note 3] He could see the descending glacier eventually drained to the Indus River and so the mountain was in the British Empire.[4] K2 is further north than the Himalayan mountains so the climate is colder; the Karakoram range is wider than the Himalayan so more ice and snow is trapped there.[5]

History of climbing on the mountain

[edit]| History of climbing K2 | |

|---|---|

Television programs | |

1938 expedition starts at 07:20 minutes | |

1938 expedition starts at 05:35 minutes | |

Houston talking about 1953 expedition (start 05:50) and narrating film (starting 15:35) but also referring to 1938 expedition |

In 1890 Roberto Lerco had entered the Baltoro Muztagh region of the Karakoram. He had reached the foot of K2 and may even have climbed a short way up its south-east spur but he did not leave an account of his journey.[9][10] The first serious attempt to climb the mountain was in 1902 by a party including Aleister Crowley, later to become notorious as "the Wickedest Man in the World". The expedition examined ascent routes both north and south of the mountain and made the best progress up the northeast ridge before they were forced to abandon their efforts.[11] Since that time K2 has developed the reputation of being a more difficult mountain to climb than Mount Everest – every route to the summit is tough.[12][note 4]

The 1909 Duke of the Abruzzi expedition reached about 20,510 feet (6,250 m) on the southeast ridge before deciding the mountain was unclimbable. This route later became known as the Abruzzi Ridge (or Abruzzi Spur) and eventually became regarded as the normal route to the summit.[15] In 1929, Aimone de Savola-Aosta, the nephew of the Duke of the Abruzzi, led an expedition to explore the upper Baltoro Glacier, near K2.[16]

Preparation for 1938 expedition

[edit]American Alpine Club plans for 1938 and 1939 expeditions

[edit]At the American Alpine Club's 1937 meeting, Charlie Houston and Fritz Wiessner were the main speakers and Wiessner proposed an expedition to climb K2 for the first time, an idea that was strongly supported. The American Alpine Club (AAC) president applied for an expedition permit via the Department of State – the British colonial authorities approved the plan for a reconnaissance, possibly leading to an attempt, in 1938 to be followed by an expedition in 1939 if the first attempt failed. Although Wiessner had been expected to lead the first expedition – he was probably the best American mountaineer and climber at the time – he backed down and suggested Houston replace him. Houston had considerable mountaineering experience – he had organized and achieved the first ascent of Alaska's Mount Foraker in 1934 and had been a climbing member on the British–American Himalayan Expedition of 1936 which reached the top of Nanda Devi, which was then and in 1938 was still the highest summit to have been climbed.[17] Their primary aim was to reconnoiter the three main ridges of K2, and make a summit attempt if possible.[18]

Team members

[edit]Bob Bates was a friend of Houston's and a fellow student at Harvard – he had twice been mountaineering in Alaska. Richard Burdsall had successfully climbed Mount Gongga in Sichuan, China. Bill House had been with Wiessner on the first ascent of Mount Waddington in British Columbia. Paul Petzoldt was a very experienced mountain guide and rock climber in Wyoming's Tetons. Unlike the others who were ivy League graduates, Petzoldt had not been to college.[18] Norman Streatfeild was a British army officer based in India who had been a transport officer on a French Karakoram expedition. He was not a highly experienced mountaineer but was good at organising the porters and at deploying the equipment.[18][19]

Equipment

[edit]They had to experiment with what food to take, eventually deciding on 50 pounds (23 kg) of pemmican, beloved of polar explorers. It was not yet known that pemmican is far too fatty for high altitudes. They chose hard biscuits that did not soften when moist. Dried fruit and vegetables were beginning to be available and they took cereal along with powdered milk. [20]

Boots were leather with hobnails, specially made for them in England. Climbing ropes were manila and hemp – no nylon. The design of the ice ax was for a long wooden shaft with a steel head forming a pick and adze.[21] Following the British example, and unlike Wiessner's expedition next year, they took very little technical climbing equipment – only ten pitons were thought sufficient. Petzoldt favoured modern devices but his professional climbing experience was not considered to be in his favor. Because he could not afford the trip, Petzoldt had been funded by another AAC member but he felt forced to spend some of his limited funds by secretly purchasing fifty pitons while he passed through Paris.[22]

Voyage and trek to K2 Base Camp

[edit]

The expedition set sail on April 14 from New York to Bombay via Europe.[21] They reached Rawalpindi on May 9 and drove just north of Srinagar to Wayul, at that time at the end of the road. Then it was a case of trekking over the Zoji La to Skardu and on via Askole to K2 Base Camp, a distance of 360 miles (580 km).[23] At Srinagar they had met with the six Sherpas they had hired in advance and who had traveled from Darjeeling. Sherpas are of Tibetan and Nepali origin but those seeking a career in mountain guiding based themselves at Darjeeling in India where pre-war British Everest expeditions had always done their recruiting.[note 5] A Sherpa was attached to each sahib – Pasang Kikuli, who had been with Houston on the British–American Nanda Devi Expedition in 1936,[note 6] was again with Houston and was the sirdar (chief Sherpa).[26] The other Sherpas were Pemba Kitar, Tse Tendrup, Ang Pemba, Sonam, and Phinsoo. Three Kashmiri shikaris (huntsmen) were appointed to maintain Base Camp: Ahdoo the cook, a major-domo and a valet.[27]

They set off with less than one hundred porters and twenty-five ponies which could only be taken as far as Yuno where they were replaced by seventy-five additional porters.[28] Local porters were hired just for a few days before new ones were taken on. At Yuno the porters refused to work for the pay offered so Bates and Streatfeild rafted back down to Skardu, 28 miles (45 km) down the torrential Shigar and Indus rivers, to get more helpful porters. At Hoto they all had to cross the Braldu River over a 200-foot (61 m)-deep gorge across a "rope" bridge made from plaited willow twigs. Askole was reached on June 3 but there Petzoldt went down with what was later diagnosed as dengue fever so Houston, who was a doctor, stayed with him while the others went on. They climbed the snout of the Baltoro Glacier and then reached Urdukas, a solitary grassy oasis just off the glacier which is the farthest local herdsmen go for grazing. At this point, Houston and Petzoldt caught up with the main party.[29]

On June 12 they reached their site for Base Camp where the porters were paid off with instructions to return in 45 days.[30]

Reconnaissance of possible ascent routes

[edit]Benefiting from the work done twenty-nine years earlier by the Duke of the Abruzzi expedition, Houston's party set out to review the various possible approaches to the summit.[30]

1909 Duke of the Abruzzi exploration

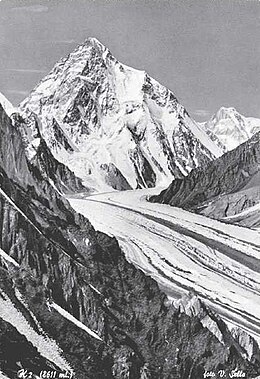

[edit]The Abruzzi party had included the photographer Vittorio Sella whose magnificent photographs were used and admired by later generations of explorers, giving a fine impression of the mountain faces and ridges of K2 and its surrounding mountains. At Concordia, where the Baltoro and Godwin-Austen glaciers merge, they had traveled up the latter. From what became the traditional base campsite they explored K2's northeast ridge, which they considered hopeless, so attempted to climb up the southeast ridge – now called the Abruzzi Ridge or Spur. Two Courmayeur guides reached about 21,000 feet (6,400 m) but this only proved the party as a whole would not manage the climb. They then went on the western side of K2, up the Savoia Glacier to a place they called the Savoia Pass at 21,870 feet (6,670 m), at the foot of the northwest ridge. Again they were thwarted so as a consolation they climbed high on Chogolisa, to about 24,275 feet (7,399 m) – the highest altitude ever reached and one that would not be exceeded until the 1922 British Mount Everest expedition.[31]

1938 reconnaissance

[edit]

Throughout the two weeks in June 1938 allocated to reconnaissance, there was stormy weather.[32] Bates and Streatfeild ventured up the Godwin-Austen Glacier from where the south face and northeast ridge of K2 seemed impossible. They explored the Savoia Glacier but on three occasions failed to reach the Savoia Pass, the way being blocked with crevasses and walls of ice. They had been hoping to find a route from this side because the 1909 survey had observed that the rock strata on the northwest ridge provided a step-like climbing route whereas on the other side, the Abruzzi Ridge, the rocks sloped downward giving insecure footing and poor places to pitch tents.[30]

Near base camp the Abruzzi Ridge appeared to be a very difficult climb on mixed rock, ice and snow, continuously steep for over 8,000 feet (2,400 m) up to a shoulder at about 26,000 feet (7,900 m). Above this, the summit pyramid could be glimpsed where there was a hanging glacier threatening both the northeast and Abruzzi ridges. On June 28 Petzoldt and House favored attempting the Abruzzi Ridge whereas Houston and Burdsall preferred investigating the northeast ridge further. On the Abruzzi Ridge it was difficult to find anywhere at all suitable for pitching a tent until on July 2 Petzoldt found a small saddle point hidden away but suitable for several tents. This decided the line of attack and the location was to become Camp II.[33]

Abruzzi Ridge line of ascent

[edit]

| Locations of camps on mountain | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camp | Altitude[1] | Camp established [note 7] |

Location | |

| feet[34] | metres | |||

| Base | 16,600 | 5,100 | (June 12)[30] | Godwin-Austen Glacier |

| I | 17,700 | 5,400 | base of Abruzzi Ridge[34] | |

| II | 19,300 | 5,900 | July 3[35] | small saddle on Ridge[36] |

| III | 20,700 | 6,300 | July 5[37] | site vulnerable to falling rocks[38] |

| IV | 21,500 | 6,600 | July 13[37] | below House's Chimney through the Red Rocks[39] |

| V | 22,000 | 6,700 | July 14[40] | top of House's chimney[41] |

| VI | 23,300 | 7,100 | July 19[42] | base of Black Pyramid/Tower[43] |

| VII | 24,700 | 7,500 | July 20[40] | plateau by ridge and ice traverse[44] |

| high point | 26,000 | 7,900 | July 21[45] | (no camp) onto Shoulder (at 25,600 ft (7,800 m))[46]

below Bottleneck Couloir (26,900 ft (8,200 m))[46] |

| Summit | 28,251 | 8,611 | summit not reached | |

Progress up mountain

[edit]

Camp II was established on July 3, but right at the start, there was a serious accident when a rock fell on a can containing most of the supply of cooking fuel, spilling all the oil. Streatfeild led a small party to the foot of Gasherbrum, hoping to find the supply left by a French group in 1936. It turned out porters had looted the fuel but Streatfeild in turn acquired some cans of food. Pemba Kitar, and the cook, Ahdoo, went off down to Askole, a march expected to take seven days, to get porters to bring up a supply of firewood. Only eight days later they arrived back at Base Camp with ten porters bringing a massive amount of cedarwood. By using this for heat at Base Camp there was sufficient fuel on the mountain.[47]

While this was going on supplies were being carried up the Ridge and, in awkward places, fixed ropes were being placed. Petzoldt's pitons were of tremendous help. Jumars had not yet been invented so the climbing technique was to knot the hemp ropes in places and simply heave upwards, hand over hand. Pasang Kikuli, Phinsoo and Tse Tendrup did most of the load-carrying as well as shifting rocks to level the platforms for tents.[37][note 8] As it turned out Camp III was sited in a dangerous position threatened by rock falls. Rocks dislodged by climbers higher up the mountain fell 500 feet (150 m) punching holes in all three tents but fortunately no one was hit.[48][note 9] At this stage Streatfeild, Burdsall and three Sherpas left to go on further reconnaissance around the mountain and only Pasang Kikuli was the only Sherpa to go any higher up the mountain.[49]

Camp IV was close to the foot of an 80 feet (24 m) vertical cliff and on July 14 Bill House managed to surmount the cliff (which they called House's Chimney) taking two and a half hours. In those days pitons were of rather soft metal and were ineffective on a hard rock so at 21,500 feet (6,600 m) House effectively had to free climb his way up the chimney without protection because there were no alternatives for getting further up the ridge.[50] It had been the hardest rock climb at that time at any comparable altitude.[51] There was then rapid progress through the Black Pyramid to reach above 25,000 feet (7,600 m) on July 19.[52]

With everyone together at Camp VI they reviewed their situation – there was only ten days of fuel and food remaining. Concerned in case bad weather would delay a descent, they decided by a vote that Houston and Petzoldt would be the climbers to up to as high as possible.[53] It was thought that the mountaineering was now technically too difficult for Sherpas so that only the four sahibs would carry supplies up to establish Camp VII – however they agreed to include Pasang Kikuli after he had pleaded with them. With Houston and Petzoldt at Camp VII on July 20, Houston was sure a summit attempt would be out of the question.[note 10] They then discovered no matches had been included in their supplies but fortunately Houston had nine matches in his pocket. After preparing them carefully with grease they got the stove to light with the third match. In the morning three more matches were used for lighting the breakfast stove. On July 21, heading without camping gear towards the Shoulder in knee-deep snow Petzoldt was the stronger climber. By 13:00 there reached the more level Shoulder and traversed over to just 900 feet (270 m) below the couloir (known later as the Bottleneck).[45]

At that point, Houston could go no higher and they turned back at 16:00 after Petzoldt had reached about 26,000 feet (7,900 m) where he found a site suitable for a tent for a future expedition.[55][56] As darkness fell they got back to their tent where they managed to light the stove with their third and last remaining match.[57] Below Camp III on the way down Pasang Kikuli shouted out when he spotted a large rock shooting down towards them and they were only just able to take cover in time. He explained that the "snowmen" had warned him to look up just at the time.[58][note 11]

Return to Srinagar and assessment

[edit]

The party got back to Base Camp by July 25, leaving the fixed ropes in place, and made the six-day trek back to Askole. Eleven more days took them to Srinagar – they were able to take a shorter route over the Skoro La pass and across the Deosai Plains because the snow had cleared since their outward trek.[25][57]

Petzoldt stayed on in India at an ashram, but after the leader of the ashram (who was himself American) died in controversial circumstances, he returned hurriedly home after there was the possibility of a charge of manslaughter.[56]

The expedition was relatively small-scale and low-cost compared with the eight-thousander expeditions of the 1950s but it found a good route – the best route – to the summit, scaling the most difficult point and getting back without serious injury. It was a well-run, united and successful reconnaissance. Ed Viesturs has described it as "a magnificent achievement".[60] Speaking of the book of the expedition, Five Miles High (Bates & Burdsall 1939), Curran says that it shows a harmonious expedition at its very best and that it should be compulsory reading for anyone contemplating going to K2".[61] Sale describes it as "one of the great expedition books".[62]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Note that Vittorio Sella was not on the 1938 expedition.

- ^ The tallest mountains measured were called "K1" and "K2" and the higher one turned out to be K2.[2]

- ^ Hence the earlier name of K2 was "Mount Godwin-Austen".[3]

- ^ K2 may be the most challenging of all the eight-thousand-metre mountains although Annapurna has a higher death rate for climbers than either Everest or K2.[13] Kauffman and Putnam liken the comparison between Everest and K2 to that between Mont Blanc and the Matterhorn in the Alps.[14]

- ^ After Pakistan independence in 1947 Sherpas were not permitted into the country so local Hunza high-altitude porters were employed by the next American expedition.[24]

- ^ Bill Tilman had arranged for Pasang Kikuli to go on the 1938 British Mount Everest expedition but Tilman agreed for him to accompany Houston instead.[25]

- ^ Dates in parentheses are when a camp was first used rather than when it was established (fully set up and stocked). For higher locations first use and establishment may be the same.

- ^ These three Sherpas were all on the 1939 American K2 expedition where Pasang Kikuli and Phinsoo both died trying to rescue Dudley Wolfe.

- ^ This site for Camp III was avoided by future expeditions as a major camp location.

- ^ Petzoldt much later claimed that he had wanted to go on and that Houston had too much seen the purpose as reconnaissance and had never been sufficiently determined to reach the summit.[54]

- ^ Conefrey writes of "yeti" but Five Miles High uses the term "snowmen".[59]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 25–27.

- ^ Isserman & Weaver (2008), p. 18.

- ^ Isserman & Weaver (2008), p. 21.

- ^ Isserman & Weaver (2008), pp. 18–21.

- ^ Curran (2005), 156/3989.

- ^ Vogel & Aaronson (2000).

- ^ Conefrey (2001).

- ^ Houston (2005).

- ^ Conefrey (2015), p. xvi.

- ^ Isserman & Weaver (2008), p. 42.

- ^ Isserman & Weaver (2008), pp. 58–60.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), p. xii.

- ^ Day (2010), pp. 181–189.

- ^ Kauffman & Putnam (1992), p. 18.

- ^ Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 18–22.

- ^ Isserman & Weaver (2008), pp. 198–199.

- ^ Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b c Viesturs & Roberts (2009), pp. 81–82.

- ^ Curran (2005), 873/3989.

- ^ Viesturs & Roberts (2009), pp. 83–84.

- ^ a b Viesturs & Roberts (2009), pp. 84–85.

- ^ Viesturs & Roberts (2009), pp. 84–86.

- ^ Viesturs & Roberts (2009), pp. 85–87.

- ^ Curran (2005), 1206/3989.

- ^ a b Houston (1939b).

- ^ Viesturs & Roberts (2009), pp. 87–88.

- ^ Houston (1939a), p. 56, 69.

- ^ Houston (1939a), pp. 56, 58.

- ^ Viesturs & Roberts (2009), pp. 89–94.

- ^ a b c d Viesturs & Roberts (2009), pp. 93–94.

- ^ Viesturs & Roberts (2009), pp. 77–80.

- ^ Viesturs & Roberts (2009), pp. 94–95.

- ^ Viesturs & Roberts (2009), pp. 93–96.

- ^ a b American Alpine Club Library (2018).

- ^ Viesturs & Roberts (2009), pp. 96–97.

- ^ Viesturs & Roberts (2009), p. 96.

- ^ a b c Viesturs & Roberts (2009), p. 98.

- ^ Viesturs & Roberts (2009), p. 99.

- ^ Viesturs & Roberts (2009), p. 101.

- ^ a b Viesturs & Roberts (2009), p. 102.

- ^ Viesturs & Roberts (2009), pp. 102–103.

- ^ Houston (1939a), p. 64.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), pp. 175–176.

- ^ Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 78–79.

- ^ a b Viesturs & Roberts (2009), pp. 103–104.

- ^ a b Curran (2005), 3981/3989.

- ^ Viesturs & Roberts (2009), pp. 96–98.

- ^ Viesturs & Roberts (2009), pp. 98–100.

- ^ Curran (2005), 911/3989.

- ^ Viesturs & Roberts (2009), pp. 99–102.

- ^ Sale (2011), p. 76.

- ^ Viesturs & Roberts (2009), pp. 100–103.

- ^ Curran (2005), 938/3989.

- ^ Viesturs & Roberts (2009), pp. 107–110.

- ^ Viesturs & Roberts (2009), pp. 104–105.

- ^ a b Sale (2011), pp. 77–78.

- ^ a b Viesturs & Roberts (2009), p. 105.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), p. 62.

- ^ Bates & Burdsall (1939), p. 247.

- ^ Viesturs & Roberts (2009), p. 110.

- ^ Curran (2005), 965/3989.

- ^ Sale (2011), p. 78.

Works cited

[edit]- American Alpine Club Library (February 9, 2018). "K2 1938: The First American Karakoram Expedition". American Alpine Club. Archived from the original on February 17, 2019.

- Bates, Robert H.; Burdsall, Richard L.; et al. (1940) [1939]. Five miles high: the story of an attack on the second highest mountain in the world by the members of the first American Karakoram expedition. London: Robert Hale.

- Conefrey, Mick (2015). "Chapter 2, The Harvard Boys". The Ghosts of K2: the Epic Saga of the First Ascent. London: Oneworld. pp. 31–65. ISBN 978-1-78074-595-4.

- Curran, Jim (2005). "Chapter 6. Cowboys on K2". K2: The Story Of The Savage Mountain (ebook). Hodder & Stoughton. pp. 848–965/3989. ISBN 978-1-444-77835-9.

- Day, Henry (2010). "Annapurna Anniversaries" (PDF). Alpine Journal: 181–189. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- Houston, C. S. (May 1939). "The American Karakoram Expedition to K2, 1938" (PDF). Alpine Journal. LI (258): 54–69. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- Houston, Charles (1939). "A Reconnaissance of K2, 1938". Himalayan Journal. 11.

- Isserman, Maurice; Weaver, Stewart (2008). "The Golden Age of Himalayan Climbing". Fallen Giants : A History of Himalayan Mountaineering from the Age of Empire to the Age of Extremes (1 ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11501-7.

- Kauffman, Andrew J.; Putnam, William L. (1992). K2: The 1939 Tragedy. Seattle, WA: Mountaineers. ISBN 978-0-89886-323-9.

- Sale, Richard (2011). "Chapter 3. The Americans Head for K2". The Challenge of K2 a History of the Savage Mountain (ebook). Barnsley: Pen & Sword Discovery. pp. 70–79. ISBN 978-1-84468-702-2. page numbers from Aldiko ebook reader Android app showing entire book as 305 pages.

- Viesturs, Ed; Roberts, David (2009). "Chapter 3. Breakthrough". K2: Life and Death on the World's Most Dangerous Mountain (ebook). New York: Broadway. pp. 79–110. ISBN 978-0-7679-3261-5. page numbers from Aldiko ebook reader Android app showing entire book as 284 pages.

Further reading/viewing

[edit]Accounts by 1938 expedition

[edit]- Bates, Robert H.; Burdsall, Richard L.; et al. (1940) [1939]. Five miles high: the story of an attack on the second highest mountain in the world by the members of the first American Karakoram expedition. London: Robert Hale.

- House, William P. (1939). "K2—1938". American Alpine Journal. III (3): 229–254. PDF version (94 MB)

- Houston, C. S. (May 1939). "The American Karakoram Expedition to K2, 1938" (PDF). Alpine Journal. LI (258): 54–69. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- Houston, Charles (1939). "A Reconnaissance of K2, 1938". Himalayan Journal. 11.

Background

[edit]- Conefrey, Mick (2001). Mountain Men: The Ghosts of K2 (television production). BBC/TLC. Event occurs at 05:35. Archived from the original on February 14, 2019. Retrieved February 17, 2019. The video is hosted on Vimeo at https://vimeo.com/54661540

- De Filippi, Filippo; H.R.H. The Duke of the Abruzzi (1912). Karakoram and Western Himalaya, 1909, an account of the expedition of H.R.H. Prince Luigi Amedeo of Savoy, Duke of Abbruzzi;. Translated by De Filippi, Caroline; Porter, H. T. photographs by Vittorio Sella. New York, Dutton.

- De Filippi, Filippo (1912). List of Illustrations and Index: Karakoram and Western Himalaya, 1909, an account of the expedition of H.R.H. Prince Luigi Amedeo of Savoy, Duke of Abbruzzi. photographs by Vittorio Sella. New York, Dutton.

- Houston, Charles S.; Bates, Robert H. (1954). K2, the Savage Mountain. McGraw Hill. (primarily about the 1953 K2 expedition but also discussing that of 1938)

- Houston, Charles (2005). Brotherhood of The Rope- K2 Expedition 1953 with Dr. Charles Houston (DVD/television production). Vermont: Channel 17/Town Meeting Television. Event occurs at (talk) 05:50 & (film) 15:35.

- Vogel, Gregory M.; Aaronson, Reuben (2000). Quest For K2 Savage Mountain (television production). James McQuillan (producer). National Geographic Creative. Event occurs at 7:20. Retrieved October 24, 2018.