Capture of Valdivia

| Capture of Valdivia | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Chilean War of Independence | |||||||

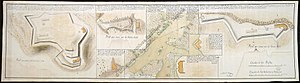

Painting of the climbing of La Aguada del Inglés in the Chilean naval and maritime museum | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Thomas Cochrane Jorge Beauchef |

Manuel Montoya Fausto del Hoyo | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 310[1] |

1,606 110 24-pounder cannons[2][1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

7 killed and 25 wounded[3] or 39 killed and wounded[4] 1 brigantine[3] |

~100 killed 106 prisoners | ||||||

The Capture of Valdivia (Spanish: Toma de Valdivia) was a battle in the Chilean War of Independence between Royalist forces commanded by Colonel Manuel Montoya and Fausto del Hoyo and the Patriot forces under the command of Thomas Cochrane and Jorge Beauchef, held on 3 and 4 February 1820. The battle was fought over the control of the city Valdivia and its strategic and heavily fortified harbour. In the battle Patriots gained control of the southwestern part of the Valdivian Fort System after an audacious assault aided by deception and the darkness of the night. The following day the demoralised Spanish evacuated the remaining forts, looted local Patriot property in Valdivia and withdrew to Osorno and Chiloé. Thereafter, Patriot mobs looted the property of local Royalists until the Patriot army arrived to the city restoring order.

The capture of Valdivia was a major victory to the Patriots as it deprived the Spanish Empire an important naval base from where to harass or quell the Republic of Chile.

Background

[edit]Despite the stunning Patriot victory at the Battle of Maipú and the subsequent declaration of independence in April 1818, the Royalists remained in control of Talcahuano, Valdivia and Chiloé.[5] With the Patriot capture of Talcahuano in January 1819,[6] the two remaining redoubts of Royalism were viewed as a threat to the nascent Republic,[5] since expeditions from Spain could arrive at them and use these fortified localities as bases to overthrow the Republic.[7] Valdivia was also a potential supply base for the Royalist guerillas led by Vicente Benavides that harassed the Patriots in La Frontera.[8]

A study made by minister Miguel de Zañartu estimated a significant fiscal income of Valdivia for the period 1807–1817, this being possibly an additional incentive for its takeover.[7]

Valdivian society was divided between Patriot and Royalist families.[9] The low-born were mostly Patriot.[9][A] On November 1, 1811, Valdivian Patriots took control of the city in a coup and aligned it with the rebel government in Santiago.[11][12] The Royalists carried out a counter-coup on March 16 1812, after which the city remained in firm Royalist control.[13][12]

Fortifications

[edit]Valdivia was the most fortified locality in the southern part of Viceroyalty of Peru, and this was known to Cochrane even before he embarked for Chile.[7] Yet before the independence war, the garrison was known to be poorly trained in artillery and the gunpowder was prone to be spoiled because of the humid climate. Further, the forts were often undermanned and faced a scarcity of provisions.[14]

The defenses at Valdivia consisted of a number of forts and batteries. On the South side of the harbour were three forts – Fort Aguada del Inglés, Fort San Carlos and Fort Amargos.[15][16] Castillo de Corral was a walled fort with furnaces for heated shots.[15] Similarly, San Carlos had also furnaces for heated shots.[16] Fort Aguada del Inglés had been built to prevent a landing in the western beaches of the southern shore.[16] For this purpose in Manuel Olaguer Feliú plans, this fort had to concentrate most of the troops in case of war.[16] Aguada del Inglés had by 1820 two 24-pounder cannons.[16] Farthest to the northwest in the southern shore lay the observation post of Morro Gonzalo with a small 4-pounder cannon.[16] The batteries on the southern shore were Chorocomayo Bajo, Chorocomayo Alto, Bolsón (Corral Viejo) and El Barro.[15]

On the Northern side was the stone walled Fort Niebla, which was able to provide crossfire with Fort Amargos and Marcera Island.[17] In 1820, it was fitted with fourteen 24-pounder cannons and one mortar.[17] It too had furnaces for heated shots.[17] Mancera Island in the centre of the harbour hosted a small garrison and one battery of six cannons.[18]

Overall, there were fifteen defensive positions in the bay totalling 110 cannons.[2]

Peru, Corral and Talcahuano

[edit]After failing to capture the Spanish fortress of Real Felipe in El Callao, Cochrane decided to assault Valdivia.[19] This was no improvisation but an objective Cochrane had kept in mind and had waited for the opportunity to carry out.[19]

The small Chilean fleet sighted Punta Galera on January 17. The next day, Cochrane boarded a chalupa and entered Corral Bay. There Cochrane's chalupa was approached by a small boat whose crew he took prisoner. The next day, the Spanish on land turned suspicious as their men had not returned, hence they opened fire against the Patriot chalupa which then moved out of the cannon range.[19] Apart from capturing local soldiers, Cochrane also learned that the Spanish ship San Telmo had still not arrived to Corral.[19] On January 19, Cochrane's fleet captured the brigantine Potrillo that was entering the bay.[20] The ship was not able to defend itself as it had left its cannons in Callao to be lighter.[3] The cargo was highly valuable including silver, gunpowder and planks from Chiloé among other things.[20] Among the captured valuables were also a 1788 chart of the port made by José de Moraleda.[20]

With all intelligence gathered, Cochrane was back in Talcahuano in January 1820.[21] There he asked –and was given– reinforcements to assault Valdivia by intendant Ramón Freire. Doing this, Freire postponed his planned offensive against the Royalist guerrillas around Biobío River south of Talcahuano.[21] Cochrane did however hide his intentions to other Patriot authorities.[21] He sent a misleading letter to the Minesterio de Marina telling he was late to Valparaíso because he was supporting Freire, yet in a separate letter Cochrane confided to Bernardo O'Higgins his true plans.[21]

The three ships with which Cochrane departed on January 28 to capture Valdivia were O'Higgins, Intrépido and Moctezuma.[22] Potrillo had been sent north to Valparaíso.[21]

Battle

[edit]

Landing and assault on Aguada del Inglés

[edit]Facing these powerful fortifications, Cochrane decided to attack the forts from land in a disguised amphibious operation. To approach the coast at Aguada del Inglés in the southwestern part of the bay, Cochrane sent men to speak with the Spanish telling them they were part of the convoy of the Spanish ship San Telmo, whose arrival they were waiting.[23] The plan worked for a while until the Spanish saw a landing boat, that had been hidden, and opened fire.[23] The ship Intrépido and seven men in were hit by a cannonball.[23] 250 soldiers commanded by Jorge Beauchef and 60 by Guillermo Miller landed in the small beach of Aguada del Inglés.[23][24] 70 to 80 Spanish soldiers descended the fort and went to confront the Patriot force with bayonets on the beach.[25][1] Being under repeated fire from the cannons of the ships the Spanish retreated.[25] At about six o'clock of the afternoon, Beauchef ordered an advance on the fort Inglés. The advance proceeded well until suddenly the bulk of the Patriot force came under heavy fire of cannons and muskets of the fort.[26][27][25] However, the darkness of the night in the nearby forest made it difficult for the defenders to shoot accurately.[27] A Patriot detachment of 70 approached the fort from behind and began to climb the walls at about 9.00 o'clock at night.[26][27][4] While the first two climbers died, defenders were eventually overcome.[27] Being fought from outside and within the fort, the Spanish panicked and abandoned the fort.[25][4]

Assault on San Carlos, Amargos and Corral

[edit]

Beauchef followed up this victory and quickly overran the forts of San Carlos and Castillo de Amargos as well as the batteries of Chorocamayo and Barros.[25][28] The commander of San Carlos was unable to prevent his troops from fleeing as the Patriots approached.[27] The cannons in this fort were also useless against this land-based assault as they were all directed towards the sea.[27] Confident of victory, Patriot soldiers ran disorderly forward to the next Royalist position in their way.[27] Carson, an American who led the forward troops, cautioned against a possible Royalist ambush and stopped the fast advance several times.[27]

At midnight, the Patriot forces stood before the Castillo de Corral, the last one the Valdivian Fort System in the southern side of the bay.[28][29] The fort of Corral was defended by about two hundred soldiers most of whom had retreated from the nearby forts.[28] The Patriots assaulted the fort from three sides, making the Spanish overestimate the size of the attacking force.[28] It was also possible the Royalist thought the attackers were the first ones of a much larger force.[30] The assault was disordered and the ensuing melée was carried out with great fury on part the Patriots.[30] Historian Gabriel Guarda labeled the assault "suicidal" and contrary to military doctrine yet understandable as Beauchef had served in Napoleon's Imperial Guard.[30] Castillo de Corral with its walls became soon more of a prison to Royalists rather than a defensive structure. The Royalist leadership surrendered much later, only once it was cornered after vigorous resistance.[30] Likely, the Royalist leaders in Castillo de Corral were drunk at that time.[28]

Colonel Manuel Montoya, the over-all commander of Valdivia and its fort system, remained in Valdivia far from the fighting.[31] From there, he sent a column of 100 men downriver from Valdivia in charge of Fernández Bobadilla to reinforce the forts in the bay.[32][4]

Royalist evacuation

[edit]After the success of the attack on the forts of the southern shore, Cochrane called a halt for the night.[citation needed] In the next morning, the ships Moctezuma and Intrépido entered the bay receiving cannon fire from Castillo de Mancera and Castillo de Niebla. Intrépido was hit by two balls that did minor damage, Moctezuma instead was able to momentarily silence some of the cannons on land with its own fire.[30] These ships arrived to the port of Corral at 8:00.[30]

Cochrane anticipated an altogether grimmer fight in the morning to capture the remaining fortifications, as he had lost the element of surprise.[citation needed] 200 soldiers were planned be used for that action.[31]

Fernández Bobadilla with his reinforcements arrived in the morning to Niebla attempting to organize a defense among demoralised soldiers.[32] Once Cochrane's assault force of 200 men approached Niebla, the efforts of Fernández Bobadilla evaporated and the garrisons of Castillo de Niebla and Mancera Island retreated upstream to Valdivia in whatever small canoes and boats they could find.[29][32][3] The dragoons of Niebla went to Valdivia by land following the northern shore of Valdivia River.[32][9] A possible cause for the unwillingness to fight was the sight of O'Higgins in the morning. The ship was almost empty, but it may have misled the Royalist to think there were more incoming Patriots.[3]

After the battle, both O'Higgins and Intrépido faced difficulties while navigating in Corral Bay. Given that Intrépido, had its hull in bad state, it was lost as it ran aground.[3]

Turmoil in Valdivia

[edit]

Meanwhile in Valdivia, Montoya made arrangements on the sly to abandon the city.[31] The soldiers that had fled from the bay arrived to the city making wild claims on the size of the Patriot force to justify their retreat.[9] A war council determined the evacuation of Valdivia for Chiloé, sparing the city from becoming a battlefield.[9] A tumultuous situation developed in the city, as soldiers sacked the houses and stores of local Patriots. Some soldiers even stayed behind the retreating army to get more loot.[9] As the last looting Royalists finally retreated, low-born Valdivians began to loot houses of local Royalists.[9] Some Royalist patrician families had to abandon the city for their countryside properties in face of rioting and plunder.[9] Both Patriot and Royalist civilians died during the Royalist and Patriot looting, respectively.[9] The crisis led prominent families to arrange meetings to discuss the situation, and in one of these, María de los Ángeles de la Guarda took the initiative to send an embassy to the Patriot forces.[9][33] Having received the embassy in Corral, Cochrane sent Beauchef with 100 soldiers to Valdivia. Once there, Beauchef assured there would not be any retaliation against local Royalists and that those who had fled the city could come back.[33] Private property was also to be respected.[33] Cochrane's nobility may have had an influence in having the Patriot invasion gain the trust of local Royalists.[33]

On Sunday February 6, Cochrane disembarked in Valdivia with troops standing in attention and the city's notables welcoming him.[34][33] Cochrane went up from the city's harbor to the plaza by the street Calle de los abastos which was subsequently renamed Paseo Libertad.[33][35] Vicente Gómez Lorca was soon unanimously elected new Governor of Valdivia.[34][B]

Aftermath

[edit]Cochrane confiscated the frigate Dolores and used it in the expedition to Chiloé Archipelago, a royalist holdout south of Valdivia.[37] Lord Cochrane was unsuccessful in his attempt to conquer the archipelago[34] and before returning north to report the results, Cochrane went back to Valdivia to collect spoils.[37] Weaponry, gunpowder, silver objects that were originally from the churches of Concepción, and valuables from the local churches were confiscated in what was an effective loot.[37][38] Dolores with her cargo was the most valuable loot and was later sold in Valparaíso.[37]

The destruction of the forts was briefly contemplated by Cochrane.[3]

Cochrane left Valdivia on February 28. Jorge Beauchef stayed in Valdivia departing soon by land with 200 soldiers to secure the mainland between Valdivia and Chiloé for the Republic.[38] Beauchef was successful in securing Los Llanos and Osorno and repelled a Royalist counter-offensive at the Battle of El Toro.[39] By October 1820, Patriots had suffered setbacks against the Royalist guerrillas near Concepción, Beauchef had left Valdivia and it was rumoured that the Governor of Chiloé, Antonio de Quintanilla, was soon to invade Valdivia by taking first Osorno and Los Llanos.[40] The said invasion did however never happen, but the Royalists continued to resist in Chiloé until 1826.[citation needed]

The clergy of the Franciscan missions around Valdivia remained sympathetic to the Royalist cause and in due time were replaced by clergy aligned with the Republic.[41][C]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Gabriel Guarda mentions that historians prior to 1953 often –and wrongly– portrayed Valdivia an overly Royalist city.[10]

- ^ According to Rodolfo Amando Philippi, in the 1850s the inhabitants of Valdivia did not considered themselves Chileans, as to them Chile lay further north.[36]

- ^ The Franciscans missions around Valdivia were part of a larger system of missions headquartered in Chillán. The Franciscans of Chillán were deemed by contemporaries to be overly Royalist.[41]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Pinochet et al. 1997, p. 193.

- ^ a b Guarda 1953, p. 241.

- ^ a b c d e f g Vargas Guarategua, Javier (2011-05-01). "Campaña de Lord Cochrane sobre Valdivia y Chiloé en 1820" (PDF). Revista de Marina (in Spanish). pp. 462–461. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-02-04. Retrieved 2021-05-03.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b c d Pinochet et al. 1997, p. 194.

- ^ a b Guarda 1970, p. 11.

- ^ Barros Arana, Diego (1852). El Jeneral Freire (in Spanish). Santiago: Imprenta de Julio Belin i Ca. p. 48.

- ^ a b c Guarda 1970, p. 12.

- ^ Guarda 1970, p. 25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Guarda 1970, p. 98.

- ^ Guarda 1953, p. 256.

- ^ Guarda 1953, p. 219.

- ^ a b Montt Pinto, Isabel (1971). Breve Historia de Valdivia (in Spanish). Editorial Francisco de Aguirre.

- ^ Guarda 1953, p. 225.

- ^ Prieto Ustio, Ester (2015). "El sistema defensivo del Antemural del Pacífico y Llave del Mar del Sur.Las fortificaciones de la Cuenca de Valdivia y la Bahía de Corral (Chile)" (PDF). In Rodríguez-Navarro (ed.). Defensive Architecture of the Mediterranean. XV to XVIII centuries (in Spanish). Editorial Universitat Politècnica de València. p. 281-288. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-02-04. Retrieved 2021-05-01.

- ^ a b c Guarda 1970, p. 36.

- ^ a b c d e f Guarda 1970, p. 37.

- ^ a b c Guarda 1970, p. 32.

- ^ Angulo, S.E. (1997). "La Artillería y los Artilleros en Chile. Valdivia y Chiloé como antemural del Pacífico". Militaria: revista de cultura militar, 10, pp. 237–264

- ^ a b c d Guarda 1970, p. 15.

- ^ a b c Guarda 1970, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d e Guarda 1970, p. 17.

- ^ Guarda 1970, p. 19.

- ^ a b c d Guarda 1953, p. 245.

- ^ Guarda 1953, p. 244.

- ^ a b c d e Guarda 1953, p. 246.

- ^ a b Guarda 1970, p. 89.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Guarda 1970, p. 90.

- ^ a b c d e Guarda 1953, p. 247.

- ^ a b Guarda 1953, p. 248.

- ^ a b c d e f Guarda 1970, p. 91.

- ^ a b c Guarda 1970, p. 94.

- ^ a b c d Guarda 1970, p. 96.

- ^ a b c d e f Guarda 1970, p. 100.

- ^ a b c Guarda 1953, p. 251.

- ^ "Municipio de Valdivia comenzará obras de reposición de Paseo Libertad". Diario de Valdivia. November 24, 2020. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ^ Rumian Cisterna, Salvador (2020-09-17). Gallito Catrilef: Colonialismo y defensa de la tierra en San Juan de la Costa a mediados del siglo XX (M.Sc. thesis) (in Spanish). University of Los Lagos.

- ^ a b c d Guarda 1953, p. 252.

- ^ a b Guarda 1953, p. 253.

- ^ Guarda 1953, p. 255.

- ^ Guarda 1953, p. 261.

- ^ a b Guarda 1953, p. 257.

Bibliography

[edit]- Guarda, Gabriel (1970). La toma de Valdivia. Santiago de Chile: Zig Zag.

- Guarda Geywitz, Fernando (1953). Historia de Valdivia (in Spanish). Santiago de Chile: Imprenta Cultura.

- Pinochet Ugarte, Augusto; Villaroel Carmona, Rafael; Lepe Orellana, Jaime; Fuente-Alba Poblete, J. Miguel; Fuenzalida Helms, Eduardo (1997) [1984]. Historia militar de Chile (in Spanish). Vol. I (3rd ed.). Biblioteca Militar. pp. 165–166.

External links and sources

[edit]- History of the fortifications of Valdivia (in Spanish)

- Capture of Valdivia (in Spanish)

Further reading

[edit]- Gonzalo Contreras. Lord Cochrane bajo la bandera de Chile. Santiago, Editorial Zig-Zag, 1993, ISBN 956-12-0812-1

- Francisco Encina. Historia de Chile. Santiago, Editorial Nascimiento, 1949.

- Jaime Eyzaguirre. O'Higgins. Santiago, Editorial Zig-Zag, 1982, ISBN 956-12-1022-3

- Renato Valenzuela Ugarte. Bernardo O´Higgins. El Estado de Chile y el Poder Naval. Santiago, Editorial Andrés Bello, ISBN 956-13-1604-8

- Conflicts in 1820

- Battles involving Chile

- Battles involving Spain

- Battles of the Spanish American wars of independence

- Battles of the Chilean War of Independence

- Battles of the Chiloé Campaign

- 1820 in Chile

- History of Los Ríos Region

- February 1820 events

- Coasts of Los Ríos Region

- Amphibious operations involving Chile