4 World Trade Center

| 4 World Trade Center | |

|---|---|

4 World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan, 2015 | |

| |

| Alternative names | 4 WTC 150 Greenwich Street |

| General information | |

| Status | Completed |

| Type | Office, Retail |

| Architectural style | Modern |

| Location | 150 Greenwich Street Manhattan, New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 40°42′37″N 74°00′43″W / 40.7104°N 74.0119°W |

| Construction started | January 2008 |

| Opened | November 13, 2013[3] |

| Cost | USD $1.67 billion[1] |

| Owner | Silverstein Properties |

| Height | |

| Roof | 978 ft (298 m) |

| Top floor | 74[2] |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 78 (including 4 basement floors) |

| Floor area | 2,500,004 sq ft (232,258.0 m2) |

| Lifts/elevators | 55 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Fumihiko Maki |

| Developer | Silverstein Properties |

| Engineer | Jaros, Baum & Bolles (MEP) |

| Structural engineer | Leslie E. Robertson Associates |

| Main contractor | Tishman Realty & Construction |

| Website | |

| wtc | |

| References | |

| [4][5][6][7] | |

| World Trade Center |

|---|

| Towers |

| Other elements |

| Artwork |

| History |

4 World Trade Center (4 WTC; also known as 150 Greenwich Street) is a skyscraper constructed as part of the new World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan, New York City. The tower is located on Greenwich Street at the southeastern corner of the World Trade Center site. Fumihiko Maki designed the 978 ft-tall (298 m) building.[8] It houses the headquarters of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ).[9]

The current 4 World Trade Center is the second building at the site to bear this address. The original building was a nine-story structure at the southeast corner of the World Trade Center complex. It was destroyed during the September 11 attacks in 2001, along with the rest of the World Trade Center. The current building's groundbreaking took place in January 2008, and it opened to tenants and the public on November 13, 2013. The building has 2.3 million square feet (210,000 m2) of space.

Site

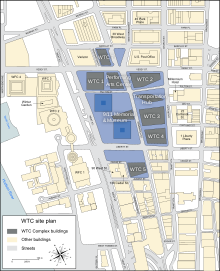

[edit]4 World Trade Center is at 150 Greenwich Street,[10] within the new World Trade Center (WTC) complex, in the Financial District neighborhood of Lower Manhattan in New York City. The land lot is bounded by Greenwich Street to the west, Cortlandt Way to the north, Church Street to the east, and Liberty Street to the south.[11][12] Within the World Trade Center complex, nearby structures include St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church and Liberty Park to the southwest; the National September 11 Memorial & Museum to the west; One World Trade Center to the northwest; and the World Trade Center Transportation Hub. 2 World Trade Center, and 3 World Trade Center to the north.[13] Outside World Trade Center, nearby buildings include 195 Broadway and the Millennium Hilton New York Downtown hotel to the northeast; the American Stock Exchange Building to the south; One Liberty Plaza to the east; and Zuccotti Park to the southeast.[14][15]

Original building (1975–2001)

[edit]

The original 4 World Trade Center was a nine-story low-rise office building completed in 1975 that was 118 ft (36 m) tall, and located in the southeast corner of the World Trade Center site. The building was designed by Minoru Yamasaki and Emery Roth & Sons. The first tenants, the Commodities Exchange Center, started to move into the building in January 1977.[16] On July 1, 1977, the Mercantile Traders finalized the move.[17] The building's major tenants were Deutsche Bank (Floor 4, 5, and 6) and the New York Board of Trade (Floors 7, 8, and 9). The building's side facing Liberty Street housed the entrance to The Mall at the World Trade Center on the basement concourse level of the WTC.

4 World Trade Center was home to commodities exchanges on what was at the time one of the world's largest trading floors (featured in the Eddie Murphy movie Trading Places). These commodities exchanges collectively had 12 trading pits.[18][19]

Destruction

[edit]The World Trade Center's Twin Towers were destroyed during the September 11 attacks, creating debris that destroyed or severely damaged nearby buildings, such as the original 4 World Trade Center.[20] Much of the southern two-thirds of the building was destroyed, and the remaining north portion virtually destroyed, as a result of the collapse of the South Tower. The structure was subsequently demolished to make way for reconstruction.

At the time of the September 11 attacks, the building's commodities exchanges had 30.2 million ounces (860,000,000 g) of silver coins and 379,036 ounces (10,745,500 g) of gold coins in the basement.[21] The coins in the basement were worth an estimated $200 million.[22] Much of the coins had been removed by November 2001;[22] trucks transported the coins out of the basement through an intact but abandoned section of the Downtown Hudson Tubes.[23] Many coins belonging to the Bank of Nova Scotia were purchased in 2002, repackaged by the Professional Coin Grading Service, and resold to collectors.[24]

Gallery

[edit]-

Former site plan, with original 4 World Trade Center at the southeast corner.

-

WTC complex and neighboring buildings, on September 23, 2001. Remaining portion of 4 WTC visible at southeast corner. Footprints of the Twin Towers and 7 WTC highlighted.

-

Site of 4 WTC in NOAA aerial image, oriented with south at left of image (September 23, 2001). Much of 4 WTC is destroyed (entire left of image), with only the damaged northern portion identifiable (at right).

-

A bird's-eye view of the World Trade Center complex, September 17, 2001, with the original locations of the buildings.

Current building

[edit]Site redevelopment

[edit]Larry Silverstein had leased the original World Trade Center from the PANYNJ in July 2001.[25] His company Silverstein Properties continued to pay rent on the site even after the September 11 attacks.[26] In the months following the attacks, architects and urban planning experts held meetings and forums to discuss ideas for rebuilding the site.[27] The architect Daniel Libeskind won a competition to design the master plan for the new World Trade Center in February 2003.[28][29] The master plan included five towers, a 9/11 memorial, and a transportation hub.[30][31] By July 2004, two towers were planned on the southeast corner of the site: the 62-story 3 World Trade Center and the 58-story 4 World Trade Center.[30] The plans were delayed due to disputes over who would redevelop the five towers.[32] The PANYNJ and Silverstein ultimately reached an agreement in 2006. Silverstein Properties ceded the rights to develop 1 and 5 WTC in exchange for financing with Liberty bonds for 2, 3, and 4 WTC.[33][34]

Japanese architect Fumihiko Maki was hired to design the new 4 World Trade Center, on the eastern part of the World Trade Center site at 150 Greenwich Street, in May 2006. Meanwhile, Norman Foster and Richard Rogers were selected as the architects for 2 and 3 World Trade Center, respectively.[35][36] The plans for 2, 3, and 4 World Trade Center were announced in September 2006.[11][12] 4 World Trade Center would be a 61-story, 947-foot-tall (289 m) building.[11][37][38] The building would have contained 146,000 sq ft (13,600 m2) of retail space in its base and 1.8×106 sq ft (170,000 m2) of offices. The lower stories would have had a trapezoidal plan, changing to a parallelogram on the upper stories.[11] The lowest stories of 4 World Trade Center and several neighboring buildings would be part of a rebuilt Westfield World Trade Center Mall.[39] The same month, PANYNJ agreed to occupy 600,000 square feet (56,000 m2) within 4 WTC,[40] paying $59 per square foot ($640/m2), a lower rental rate than what Silverstein had wanted.[41][42] The city government offered to rent another 581,000 square feet (54,000 m2),[43] thus allowing Silverstein to obtain a mortgage loan for the tower's construction.[44] Silverstein would be allowed to evict the city government if he could rent out the space at market rate.[43]

As part of the project, Cortlandt Street (which had been closed to make way for the original World Trade Center) was planned to be rebuilt between 3 and 4 WTC.[45] The plans for Cortlandt Street affected the design of the lower stories of both 3 and 4 WTC, as one of the proposals called for an enclosed shopping atrium along the path of Cortlandt Street, connecting the two buildings.[46] The street was eventually rebuilt as an outdoor path.[47] Final designs for 2, 3, and 4 WTC were announced in September 2007.[48][49] The three buildings would comprise the commercial eastern portion of the new World Trade Center, contrasting with the memorial in the complex's western section.[50] At the time, construction of 4 WTC was planned to begin in January 2008.[51] As part of its agreement with the PANYNJ, Silverstein Properties was obliged to complete 3 and 4 WTC by the end of 2011.[52]

Construction

[edit]Initial progress

[edit]

In 2007, the PANYNJ started constructing the East Bathtub, a 6.7-acre (2.7 ha) site that was to form the foundations of 3 and 4 WTC.[53] The process involved excavating a trench around the site to a depth of 70 feet (21 m), then constructing a slurry wall around the site.[54] The PANYNJ was supposed to give the site to Silverstein Properties at the end of 2007; the contractors would have received a $10 million bonus if they had completed the work early.[55] If Silverstein did not receive the site by January 1, 2008, the PANYNJ would pay Silverstein $300,000 per day until the site was transferred.[53][56] The agency ultimately gave the site to Silverstein on February 17, 2008.[57][58] The PANYNJ paid a $14.4 million penalty for turning over the site 48 days after the deadline.[55]

The PANYNJ voted in early 2008 to extend the deadline for 4 WTC's completion to April 2012.[52][59] Meanwhile, police officials expressed concern that the building's all-glass design posed a security risk.[60] A study published in early 2009 predicted that 4 WTC, the first of Silverstein's three towers at the World Trade Center site, would not be fully leased until 2014 due to the financial crisis of 2007–2008.[61] 4 WTC's construction was temporarily halted that March after city officials found that workers were operating a construction crane without a permit.[62] Disputes between the PANYNJ and Silverstein continued through late 2008, when Silverstein claimed that the agency owed him $300,000 per day for failing to demolish a barrier around the site, as the barrier prevented him from erecting the tower's foundations. The PANYNJ claimed that the barrier was several feet outside the excavation site and that it did not owe Silverstein anything.[63] That December, an arbitration panel ruled that the PANYNJ owed Silverstein an extra $20.1 million.[64]

By May 2009, Silverstein wanted the PANYNJ to fund the construction of 2 and 4 WTC, but the PANYNJ was only willing to provide funding for 4 WTC, citing the Great Recession and disagreements with Silverstein.[65][66] At the time, the PANYNJ had leased one-third of 4 WTC's office space, but no tenant had been signed for 2 WTC.[67] Silverstein also held an option to lease space to the city government for $59 per square foot ($640/m2), but he was reluctant to exercise the option, since he believed that market-rate rents for the space would increase drastically when the building opened.[66] Silverstein expressed confidence that the building would attract financial tenants since it was close to Wall Street.[68] Three PureCell fuel cells were delivered at the World Trade Center site in November 2010, providing about 30 percent of 4 WTC's power.[69] By the end of that year, the building had reached the tenth story; the project to date had been funded entirely by insurance proceeds.[70]

Funding and completion

[edit]A New York state board voted in November 2010 to allow Silverstein to finance 4 WTC and another tower with up to $200 million of bonds from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.[71] Silverstein also wanted to sell $1.36 billion worth of Liberty bonds to fund 4 WTC's completion.[72] Silverstein decided in December 2010 to postpone the bond offering because of instability in the municipal bond market.[70][73] Early the next year, he exercised his option to lease space to the New York City government.[74][75] After the muni market stabilized, the PANYNJ planned to vote on the Liberty bond offering in early 2011.[76] The vote was delayed after several institutional investors objected to the fact that the Liberty bonds would have greater seniority than a bond offering that had previously been placed on the building.[77] If the Liberty bonds were not sold by the end of that year, Silverstein would not have enough money to complete the tower.[78]

Meanwhile, during early 2011, the building was constructed at an average rate of one floor per week,[79][80] and the building had reached the 23rd floor by May 2011.[80][81] After five months of negotiations, the PANYNJ announced a revised financing plan for the tower in September 2011, in which the Liberty bonds were subordinate to the existing bond offering.[82][83] The agency started selling Liberty bonds in November 2011.[84][85] The building's steel frame was built first, followed by the concrete core and the exterior curtain wall.[79] The building had reached the 61st story by the beginning of 2012.[86] A cable on one of the building's construction cranes snapped on February 16, 2012, dropping a steel beam 40 stories;[87][88] no one was seriously injured, and work resumed shortly afterward.[89] The building's superstructure was topped out on June 26, 2012, when workers installed the final steel beam on the 72nd floor.[90][91] In the two days after the tower's topping-out, there were two construction accidents, neither of which resulted in serious injuries.[92]

The building's basements were flooded in late 2012 during Hurricane Sandy, although the tower was still expected to be completed the following year.[93] Structural steel and concrete completed by June 1, 2013, followed by the removal of construction fencing in September 2013.[94] The building opened on November 13, 2013, along with the neighboring section of Greenwich Street.[95][96] It was the second tower to open as part of the new World Trade Center, after 7 World Trade Center.[97] 4 World Trade Center had cost US$1.67 billion to build, having been funded by insurance payouts and Liberty bonds.[98] At the time, the PANYNJ and the city government were the building's only tenants.[99][100] Though the two governmental tenants collectively occupied around 60 percent of the building,[101][102] the Financial Times reported that some of the space could be subleased.[101] Janno Lieber of Silverstein Properties expressed optimism that the building's design would attract tenants, saying: "We have a building that's going to feel like a tower on Park Avenue."[99]

-

Construction on March 26, 2011.

-

Construction on August 7, 2011.

-

Construction on October 4, 2011.

-

Construction on March 12, 2012.

-

Construction on October 17, 2012.

Usage

[edit]

The first tenants to move in were the PANYNJ and the city government.[103] The New York City government leased 581,642 sq ft (54,036.3 m2) of space in the completed building.[104] The PANYNJ leased approximately 600,766 sq ft (55,813.0 m2) for its headquarters,[105][104] having relocated in 2015 from 225 Park Avenue South in Gramercy Park, Manhattan.[106] When 4 WTC opened, there was relatively low demand for office space in lower Manhattan, in part because many of the area's financial firms were downsizing their spaces.[107][108] There was so little demand for office space in the new tower that Silverstein rented out the vacant space for events, charging $50,000 per day for each floor.[109][110] According to The Wall Street Journal, these included a Super Bowl commercial, a film shoot for the 2014 movie Annie, and a wine-tasting event.[110]

By July 2015, the tower was 62 percent leased.[111] A February 2017 announcement by Spotify that it would lease floors 62 through 72 for its United States headquarters, along with a subsequent expansion announcement that July, brought 4 World Trade Center to full occupancy.[112][113] SportsNet New York, carrier of New York Mets broadcasts, moved its headquarters from 1271 Avenue of the Americas to an 83,000 sq ft (7,700 m2) facility in 4 WTC.[114] The SportsNet New York studios in 4 WTC also double as the New York City studios for NFL Network, hosting their morning show Good Morning Football.[115]

Silver Art Projects, a nonprofit organization operated by Larry Silverstein's grandson Cory Silverstein, opened 28 art studios on the 28th floor in 2020.[116][117] Twenty-five of the studios are reserved for the program's artists, who are selected through an annual application process and occupy each studio for free, while the remaining three studios are for the program's mentors.[117]

Architecture

[edit]4 WTC is described as being either 977 feet (298 m)[98][118] or 978 feet (298 m) tall,[119][120] with 2.3 million square feet (210,000 m2) of office space.[121]

Form and facade

[edit]

The facade is a curtain wall with glass panes that span the full height of each story.[79] The facade consists of glass panes measuring 5 feet (1.5 m) wide and 13 or 14 feet (4.0 or 4.3 m) tall.[102] Most of the facade is made of reflective glass, except at the lobby, where the facade is made of clear glass.[122] Five of the lowest stories are mechanical floors and contain narrow vertical louvers. The western facade of the tower, which faces the National September 11 Memorial, does not have louvers.[98] The New York Daily News wrote that Maki and Associates wanted the building's design to "pay deference to the memorial".[97] Jaros, Baum & Bolles was the MEP engineer.[123]

According to Engineering News-Record, Maki and Associates had designed 4 WTC as a "minimalist tower with an abstract sculptural presence".[79] The upper floors accommodate offices using two distinct floor shapes. Floors 7 to 46 each span 44,000 square feet (4,100 m2) and are parallelogram in plan, reflecting the shape of the World Trade Center site. the shape of a parallelogram. Floors 48 to 63 each cover 36,000 square feet (3,300 m2) and are trapezoidal in plan.[79] At the two obtuse angles of the parallelogram, there are deep grooves along the facade.[98] The top story contains a penthouse office.[124]

Structural features

[edit]The structural engineer for the building is Leslie E. Robertson Associates, founded by Robertson, the chief engineer for the original Twin Towers in the 1960s.[125] The tower's foundation is composed of concrete footings that descend to the underlying bedrock. When the original World Trade Center was developed, the contractors found that there was a gap in the bedrock at the southeast corner of the site. Although the bedrock under most of the site is 70 feet (21 m) deep, the southeast corner contains a pothole, where the bedrock descends to 110 feet (34 m) because of erosion during the Last Glacial Period.[126] The current tower's foundation is surrounded by a slurry wall.[54] The slurry wall is largely anchored to the bedrock, except at the southeast corner of the site, where the pothole made this impossible.[126]

DCM Erectors manufactured the steel for the building's superstructure.[127][128] The superstructure consists of a steel frame weighing 25,000 short tons (22,000 long tons; 23,000 t). In addition, the building uses 100,000 cubic yards (76,000 m3) of concrete and 17,000 short tons (15,000 long tons; 15,000 t) of rebar. The center of the tower contains a mechanical core made of reinforced concrete, which includes mechanical equipment, stairs, and elevators.[79] Schindler manufactured the building's elevators, which operate at a speed of 1,800 feet per minute (550 m/min).[129][130] The retail space on the lower stories contains six escalators, two passenger elevators, and two freight elevators. The upper stories are served by 37 elevators, which consist of 34 passenger elevators and three service elevators.[130]

Interior

[edit]Lower stories

[edit]

Six floors are used for retail. They consist of the ground floor, the three floors immediately above the ground floor as well as the two floors below ground.[79] The retail space occupies the eastern part of the ground floor.[98] The lower levels of the building are used by retail businesses, including Eataly.[131] These are connected via an underground shopping mall and concourse, connecting to the PATH and the New York City Subway via the World Trade Center Transportation Hub.[95][132]

The building's ground-floor lobby is two stories high,[133] with a 46-foot (14 m) ceiling.[132][118] The lobby occupies the western part of the ground floor, facing the National September 11 Memorial.[98][134] The space contains wood-beamed ceilings, white-granite floors,[95] and Swedish black granite walls.[98][134] Suspended from the lobby's ceiling is Kozo Nishino's sculpture Sky Memory,[119][135] which consists of seven pieces of titanium trusses collectively weighing 474 pounds (215 kg).[122] Sky Memory measures 98 feet (30 m) across and hangs 22 feet (6.7 m) above the floor.[122][135] The lobby also contains Vandal Gummy, a 7-foot-tall (2.1 m) sculpture of a bear by street artist WhIsBe.[136] The artist Ivan Navarro designed an LED sculpture near the bottom of the lobby's escalators.[137] Leading from the lobby are three hallways, where video art is displayed on wood-paneled walls.[133][138] The Wall Street Journal wrote that 4 WTC's lobby "will be the largest lobby by volume in New York".[138]

Critical reception

[edit]When the building was being constructed, David W. Dunlap of The New York Times wrote that 4 WTC was "the biggest skyscraper New Yorkers have never heard of".[139] The Wall Street Journal wrote that the lobby "offers a grand front to the World Trade Center Memorial" and that the effect of the lobby's design "is intriguingly calming for a building soon to rest at the heart of the Financial District."[138] Upon the tower's opening, Daniel Libeskind wrote: "The WTC site has emerged from 12 years of contention and construction to become what we all hoped it would be: a place that will show the world everything that is great about cities, especially New York."[140]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Dunlap, David W. (June 24, 2012). "A 977-Foot Tower You May Not See, Assuming You've Even Heard of It". City Room. Archived from the original on September 9, 2021. Retrieved October 26, 2016.

- ^ "Stacking Diagram | 4 World Trade Center | Silverstein Properties". 4wtc.com. Archived from the original on November 16, 2013. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ^ "|| World Trade Center ||". Wtc.com. December 31, 2013. Archived from the original on December 26, 2018. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ^ "Emporis building ID 252969". Emporis. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "4 World Trade Center". SkyscraperPage.

- ^ 4 World Trade Center at Structurae

- ^ "4 World Trade Center". Skyscraper Center. CTBUH. Archived from the original on May 6, 2021. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ "Designs for the Three World Trade Center Towers Unveiled" (Press release). Lower Manhattan Development Corporation. September 7, 2006. Archived from the original on October 17, 2006. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ "Contact Us". Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived from the original on December 10, 2019. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey Corporate Offices 4 World Trade Center 150 Greenwich Street New York, NY 10007

- ^ Satow, Julie (July 18, 2012). "Sundered Greenwich Street Will Be Rejoined". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Dunlap, David W. (September 8, 2006). "A First Look at Freedom Tower's Neighbors". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 21, 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ a b Chung, Jen (September 7, 2006). "Vision of World Trade Center in the Future". Gothamist. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ "The World Trade Center". Official World Trade Center. May 6, 2019. Archived from the original on March 30, 2020. Retrieved August 14, 2022.

- ^ "185 Greenwich Street, 10007". New York City Department of City Planning. Archived from the original on August 14, 2022. Retrieved March 25, 2021.

- ^ White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ "History of the Twin Towers". PANYNJ.gov. 2013. Archived from the original on December 28, 2013. Retrieved September 11, 2015.

- ^ "Mercantile Traders Move to Trade Center and a New Place to Shout About". The New York Times. New York City. July 2, 1977. p. 32. Archived from the original on February 19, 2022. Retrieved February 19, 2022.

- ^ Kershaw, Sarah (October 9, 2001). "Glad to Be in the Pits, Wherever They Are; Commodity Traders Had Backup Plan". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 10, 2022. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ Colkin, Eileen (September 9, 2002). "One year later: Forward strides". InformationWeek. No. 905. pp. 32–34. ProQuest 229130559.

- ^ Glanz, James; Lipton, Eric (February 12, 2002). "Rescuing the Buildings Beyond Ground Zero". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 1, 2019. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ Fuerbringer, Jonathan (September 15, 2001). "After the Attacks: The Commodities; Hoard of Metals Sits Under Ruins Of Trade Center". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ a b "Millions in Gold, Silver Recovered From Rubble". Los Angeles Times. November 1, 2001. Archived from the original on September 10, 2022. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (July 25, 2005). "Below Ground Zero, Stirrings of Past and Future". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ Martinez, Alejandro J. (August 6, 2003). "'Sept. 11' Coins Carry Hefty Markups, Baggage". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ Smothers, Ronald (July 25, 2001). "Leasing of Trade Center May Help Transit Projects, Pataki Says". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 21, 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ Bagli, Charles V. (November 22, 2003). "Silverstein Will Get Most of His Cash Back In Trade Center Deal". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 13, 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ McGuigan, Cathleen (November 12, 2001). "Up From The Ashes". Newsweek. Vol. 138, no. 20. pp. 62–64. ProQuest 1879160632.

- ^ Libeskind, Daniel (2004). Breaking Ground. New York: Riverhead Books. pp. 164, 166, 181, 183. ISBN 1-57322-292-5.

- ^ Wyatt, Edward (February 27, 2003). "Libeskind Design Chosen for Rebuilding at Ground Zero". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 21, 2022. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- ^ a b Dunlap, David W.; Collins, Glenn (July 4, 2004). "A Status Report: As Lower Manhattan Rebuilds, a New Map Takes Shape". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 13, 2022. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ Frangos, Alex (October 20, 2004). "Uncertainties Soar At Ground Zero". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on September 10, 2022. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ Satow, Julie (February 20, 2006). "Ground Zero Showdown: Freedom Tower puts downtown in bind". Crain's New York Business. Vol. 22, no. 8. p. 1. ProQuest 219177400.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (April 28, 2006). "Freedom Tower Construction Starts After the Beginning". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 15, 2009. Retrieved November 19, 2008.

- ^ Todorovich, Petra (March 24, 2006). "At the Heart of Ground Zero Renegotiations, a 1,776-Foot Stumbling Block". Spotlight on the Region. 5 (6). Regional Plan Association. Archived from the original on June 5, 2008. Retrieved November 19, 2008.

- ^ "Rogers, Maki to design towers at Ground Zero" (PDF). Architectural Record. Vol. 194, no. 6. June 2006. p. 44. ProQuest 222120847. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 10, 2022. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ Frangos, Alex (May 18, 2006). "Triplet Towers". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on September 10, 2022. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ "Designs for three World Trade Center Towers Unveiled" (Press release). Lower Manhattan Development Corporation. September 7, 2006. Archived from the original on May 28, 2013. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- ^ Frangos, Alex (September 8, 2006). "Plans for Three Trade Center Towers Are Unveiled; Details Need to Be Finalized For Designs and Outlays; 'Beacon,' Spires, Simplicity". Wall Street Journal. p. B2. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 398987302.

- ^ Hudson, Kris (January 17, 2008). "At Ground Zero, Optimism Returns". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on August 13, 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ McGeehan, Patrick (September 19, 2006). "Employees Say No to Freedom Tower". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ Frangos, Alex (September 21, 2006). "Accord on Rebuilding WTC Nears". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 19, 2022.

- ^ Bagli, Charles V. (September 22, 2006). "An Agreement Is Formalized on Rebuilding at Ground Zero". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ a b Frangos, Alex (September 22, 2006). "Pact May Mean Rebuilding Delay At Ground Zero". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on June 18, 2021. Retrieved September 19, 2022.

- ^ Bagli, Charles V. (September 14, 2006). "In Plan for 4 Ground Zero Towers, Rent Remains Sticking Point". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (November 24, 2005). "Does Putting Up a Glass Galleria Count as Bringing Back a Street?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 1, 2018. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (July 6, 2006). "Debating the Path of Cortlandt Street". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 13, 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (October 25, 2012). "Missing for 50 Years, a Bit of Cortlandt Street Will Return". City Room. Archived from the original on August 21, 2022. Retrieved August 19, 2022.

- ^ Feiden, Douglas; Grace, Melissa (September 7, 2007). "WTC tower sketches are pictures of safety". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on August 13, 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ Chan, Sewell (September 6, 2007). "Activity Picks Up as 9/11 Anniversary Approaches". City Room. Archived from the original on August 13, 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (September 7, 2007). "Developers Unveil Plans for Trade Center Site". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 13, 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ Drury, Allan (September 11, 2007). "Ground Zero rebuilding may finally be moving". The Journal News. p. C.8. ProQuest 442960978.

- ^ a b Bagli, Charles V. (May 23, 2008). "Merrill Lynch Weighs Putting Headquarters at Ground Zero". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 13, 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ a b Collins, Glenn (January 13, 2008). "Between Rock and the River, the Going Is Slow, and Costly". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 13, 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ a b Dunlap, David W. (January 24, 2007). "One Steel Cage Up, and Many More to Follow". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 13, 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ a b Collins, Glenn (February 20, 2008). "Work on Site at Trade Center Is Completed 48 Days Late". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 13, 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ "Port misses deadline and says 'worst' construction noise is almost over". amNewYork. January 10, 2008. Archived from the original on August 13, 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ Admin (February 20, 2008). "WTC Site Construction Update, February 2008". 3 World Trade Center. Archived from the original on August 13, 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ Dupré, Judith (2016). One World Trade Center: Biography of the Building. Little, Brown. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-316-35359-5. Archived from the original on August 13, 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ Arak, Joey (May 22, 2008). "Freedom's Friends Delayed, But Tower 3 May Get Lynch'd". Curbed NY. Archived from the original on August 21, 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ Smith, Greg B. (February 24, 2008). "Pros fear new towers at World Trade Center site have security gaps". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on August 14, 2022. Retrieved August 14, 2022.

- ^ Gralla, Joan (April 16, 2009). "World Trade Center rebuild faces decades of delays". Reuters. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved August 19, 2022.

- ^ Kates, Brian (March 11, 2009). "City Lowers Boom on Crane Hazard on Wtc Street". New York Daily News. p. 6. ProQuest 306249972.

- ^ Feiden, Douglas (October 9, 2008). "Trade Center's 300G-a-day Wall of Shame Hampers Plans". New York Daily News. p. 15. ProQuest 306222539.

- ^ "Port Authority wastes $20M more at bottomless Ground Zero pit". New York Daily News. December 13, 2008. Archived from the original on March 28, 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ "Port Authority wants to dump three of five proposed skyscrapers for WTC site". New York Daily News. May 11, 2009. Archived from the original on April 24, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ a b Agovino, Theresa (May 18, 2009). "Port Authority vs. Silverstein feud heads to Gracie Mansion". Crain's New York Business. Vol. 25, no. 20. p. 4. ProQuest 219150700.

- ^ Lewis, Christina S. N. (May 20, 2009). "Silverstein and Officials Talk Trade Center -- Again". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on February 26, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ Bagli, Charles V. (April 24, 2010). "As Tower Rises, So Do Efforts to Buy In". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ Troianovski, Anton (November 1, 2010). "WTC Taps Fuel Cells". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on May 10, 2015. Retrieved July 31, 2022.

- ^ a b Brown, Eliot; Neumann, Jeannette (December 9, 2010). "World Trade Center Bond Offer Delayed". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on January 25, 2022. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ Brown, Eliot (November 30, 2010). "WTC Builder Could Get More U.S. Aid". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on March 22, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ Brown, Eliot (September 13, 2010). "Liberty Bonds Stalled". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on June 17, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ "WTC bond sale delayed". Crain's New York Business. December 10, 2010. Archived from the original on October 2, 2022. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ Associated Press (February 26, 2011). "Trade Center Developer Exercises Option to Lease 14 Floors to the City". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 17, 2022. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ Lisberg, Adam (February 26, 2011). "City Gets Real, Um, Bargain?". New York Daily News. p. 2. ProQuest 853875326.

- ^ Brown, Eliot; Corkery, Michael (March 24, 2011). "Muni Woes May Hit World Trade Center Rebuilding". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on January 25, 2022. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ Brown, Eliot (April 18, 2011). "New Delay at Ground Zero". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on January 7, 2012. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ Pincus, Adam (April 13, 2011). "WTC bonds must sell by end of year or risk delay: Port Authority". The Real Deal New York. Archived from the original on November 27, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g D'Amico, Esther (September 8, 2011). "4 WTC: Out of the Spotlight". Engineering News-Record. Archived from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ a b Brown, Eliot (May 3, 2011). "New WTC Towers Rise Amid Doubts". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on December 17, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ Philips, Ted (May 9, 2011). "Rebirth at Ground Zero After Years of Setbacks, All the Pieces of the Wtc Site Are Coming Together". Newsday. p. A3. ProQuest 865161671.

- ^ "Port Authority nears bond deal to finance 4 WTC construction". The Real Deal New York. September 22, 2011. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ Brown, Eliot (September 22, 2011). "Port Authority Plans WTC Bond Change". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on December 28, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ "Silverstein, PA to finally offer 4 WTC bonds in November". The Real Deal New York. October 21, 2011. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ "World Trade Center Bond Yields Drop as Investors Seek Safety". Bloomberg. November 1, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ Brown, Eliot (January 30, 2012). "Tower Rises, And So Does Its Price Tag". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ "UPDATE: World Trade Center Crane Accident: Crane Cable Snaps, Worker Hurt". Observer. February 16, 2012. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ "World Trade Center Crane Drops Steel Beams 40 Stories in Accident". DNAinfo New York. February 16, 2012. Archived from the original on November 10, 2017. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ Yan, Ellen (February 17, 2012). "WTC work to resume after accident at site". Newsday. p. A9. ProQuest 921691076.

- ^ "Last beam in place at 4 World Trade Center". Times Union. June 26, 2012. Archived from the original on August 3, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ Newcomb, Tim (June 27, 2012). "4 World Trade Center Tops Out". Time. Archived from the original on August 13, 2014. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ "Crane Carrying Beam Crashes Into 4 World Trade Center, Shattering Windows". DNAinfo New York. June 27, 2012. Archived from the original on November 18, 2017. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ Levitt, David (November 1, 2012). "Lower Manhattan Offices Suffer from Sandy". Treasury & Risk. Breaking News. ProQuest 1125341627.

- ^ "Lower Manhattan: 4 World Trace Center (150 Greenwich Street)". Archived from the original on July 28, 2012. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

- ^ a b c Fox, Alison (November 14, 2013). "Another World Trade Center Tower Arrives". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on October 2, 2022. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ Newman, Andy; Correal, Annie (November 13, 2013). "New York Today: Skyward". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- ^ a b Chaban, Matt (October 24, 2013). "World Power First Look at Dignified 4 Wtc Marks Ground Zero's Rebirth". New York Daily News. p. 13. ProQuest 1444578633.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dunlap, David W. (June 24, 2012). "A 977-Foot Tower You May Not See, Assuming You've Even Heard of It". City Room. Archived from the original on July 17, 2022. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ a b Geiger, Daniel (May 13, 2013). "WTC site sits empty as rivals lease up". Crain's New York Business. Vol. 29, no. 19. p. 1. ProQuest 1353337479.

- ^ Raval, Anjli (May 28, 2013). "World Trade Center struggles to find tenants". Financial Times. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ a b Raval, Anjli (November 12, 2013). "World Trade Center tower opens with large vacancies". Financial Times. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ a b "4 World Trade Center Opens, and One World Trade Center Named Tallest U.S. Building". Contract. Vol. 54, no. 10. December 2013. p. 18. ProQuest 1465241527.

- ^ "NYC's World Trade Tower Opens 40% Empty in Revival". Bloomberg.com. November 12, 2013. Archived from the original on August 13, 2021. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ a b Dunlap, David W. (July 9, 2008). "Answers About Ground Zero Rebuilding". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved July 9, 2008.

- ^ 150 Greenwich St., Maki and Associates, Architectural Fact Sheet - September 2006 Archived February 28, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved February 9, 2007

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (March 4, 2015). "With Newfound Modesty, Port Authority Returns to the World Trade Center". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

After 14 years near Union Square, the agency's headquarters have returned to a spot at the World Trade Center, where they had been from 1973 until Sept. 11, 2001.[...]the interim board room at 225 Park Avenue South, at East 18th Street.

- ^ Samtani, Hiten (November 12, 2013). "4 WTC to glut already limping Downtown office market". The Real Deal New York. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ Levitt, David M. (November 12, 2013). "NYC's World Trade Tower Opens 40% Empty in Revival: Real Estate". Bloomberg. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ Samtani, Hiten (February 5, 2014). "WTC is a high-end party venue — for now". The Real Deal New York. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ a b Dawsey, Josh (February 5, 2014). "Until the Tenants Come Home, World Trade Plays Host". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ "Silverstein Signs Four More Tenants at 4WTC". Real Estate Weekly. July 29, 2015. Archived from the original on February 20, 2016. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ "Spotify deal makes 4 World Trade Center the complex's first fully leased tower". Curbed NY. Archived from the original on August 30, 2021. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ "Spotify Expands by 100K SF at 4 WTC, Bringing Tower to Full Occupancy". Commercial Observer. July 5, 2017. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ "Mets broadcaster SportsNet moves HQ to 4 WTC". The Real Deal. November 9, 2015. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- ^ Dachman, Jason (October 26, 2018). "NFL Media Ramps Up for Exclusive London Broadcast; Good Morning Football Preps for Move to SNY". Sports Video Group. Archived from the original on September 4, 2021. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- ^ Sheets, Hilarie M. (February 2, 2022). "Studio residency at the World Trade Center reserves space for formerly incarcerated artists". The Art Newspaper - International art news and events. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ a b Zornosa, Laura (March 26, 2022). "These Artists' Hunt for Studio Space Ended at the World Trade Center". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ a b "World Trade Center – Tower 4 – Tectonic". Tectonic – Tectonic Engineering Consultants, Geologists & Land Surveyors, D.P.C. December 4, 2019. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ a b "Go inside - and on top of". New York Daily News. October 23, 2013. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ "Marking A Milestone: 4 World Trade Center Opens". CBS News. November 14, 2013. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ Moses, Claire (October 27, 2014). "Amid tighter security, Silverstein's 4 WTC opens". The Real Deal New York. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ a b c Dunlap, David W. (August 7, 2013). "At the World Trade Center Site, a Space Begins to Open Up". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ "4 World Trade Center - The Skyscraper Center". www.skyscrapercenter.com. Retrieved November 10, 2022.

- ^ Hughes, C. J. (October 2, 2012). "Penthouse Offices Leasing Slowly in Midtown". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ Post, Nadine M. (September 18, 2006). "Ground Zero Office Designs Hailed as Hopeful Symbols". Engineering News-Record. p. 12.

- ^ a b Dunlap, David W. (September 22, 2008). "At Ground Zero, Scenes From the Ice Age". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 31, 2022. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ Rashbaum, William K. (October 17, 2013). "World Trade Center Contractor Is Said to Be Focus of Inquiry Into Misuse of Funds". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ Brown, Eliot (January 18, 2012). "Steel Firm's Woes Snag WTC". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on February 18, 2013. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ "Spotify Will Move to WTC; Expand Staff by 1,000". The Wall Street Journal. February 15, 2017. Archived from the original on August 20, 2020. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ a b "Elevators Bring Efficiency, Speed, and Style to 4 World Trade Center". Facilitiesnet. September 22, 2022. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ Fishbein, Rebecca. "First Look Inside The Gigantic New Eataly Location At 4 World Trade Center". Gothamist. Archived from the original on August 29, 2016. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- ^ a b Alvarez, Maria (November 14, 2013). "4 World Trade Centers opening marks Manhattan milestone". Newsday. p. A29. ProQuest 1457749319.

- ^ a b Samtani, Hiten (September 23, 2013). "Developers bring lobbies back to limelight". The Real Deal New York. Archived from the original on July 31, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ a b The Christian Science Monitor (November 13, 2013). "4 World Trade Center opens, a shining symbol of a vibrant New York". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ a b Dailey, Jessica (August 8, 2013). "World Trade Center Redevelopment". Curbed NY. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ Feitelberg, Rosemary (June 20, 2017). "Artist WhisBe Brings His Vandal Gummy Series to New York's 4 World Trade Center Building". WWD. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ "In the News: Let There Be Neon Art". Tribeca Citizen. June 28, 2017. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ a b c Paletta, Anthony (September 23, 2013). "Architecture of Passage". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ Colman, David (October 10, 2013). "Peering Past New York's Locked Doors". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ Libeskind, Daniel (November 12, 2013). "Libeskind: Learning From the World Trade Center Wrangles". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved October 2, 2022.